The legend of the Golem, the being created from clay by Rabbi Loew in the ghetto of Prague, has transcended its origins in Jewish folklore to become a metaphor for the fear of one’s own creations, which can escape all control and turn against those who conceived them. Rabbi Loew models and gives life to the Golem to protect his community by writing on its forehead the word “emet” (truth), which also means truthfulness and righteousness. When the creature loses control and threatens innocent beings, Loew erases the word from its forehead, or destroys it, according to the multiple versions of the popular tale. In other texts, the Golem is described simply as a servant, without mind or soul, that goes to work and is put away in a corner when it is no longer needed, like a household appliance or the helpful robots that populate American science fiction fantasies of the 1950s.

Undoubtedly, the golem embodies the desires and fears we project onto computers and all the technology stemming from the accelerated development of computer science in the last fifty years, especially artificial intelligence (AI), which is currently in the focus of public opinion. But before computers, the clay creature already represented the specter of the Other, that which is strange and incomprehensible, counterposed to the order of an authoritarian society that, whether as utopia or dystopia, is made up of perfect individuals, devoid of weaknesses and emotions. Underlying it all is the word that creates and dictates, be it the mystical letter combinations of the kaballah, legal systems or programming code. The creature and the loss of control over it are the key elements of the many stories that derive from the myth of the Golem, from Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley’s Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus (1818) to the numerous versions that already have a robot or an intelligent machine as the protagonist. But what usually remains in the background in these stories is the raw material that gives shape to the creature.

In Raw, Moisés Mañas rereads the oldest versions of the legend of the Golem to focus on this creation as something formless, raw, that acquires its own entity and function through a word that represents truth. The artist associates this amorphousness and the concept of truth with the data that machines collect from their environment, through sensors, or from our interaction with them, processing the vast amount of information that we provide with our actions on and off the net (if it is still possible to be “off the net”). This data, which we usually ignore and consider worthless, we give away to companies that offer us seemingly free services and devices without which we don’t know where to go. They are a surplus of our daily activity, something that sprouts naturally from every interaction with the screen and is deposited in some hidden place, where it settles.

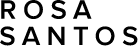

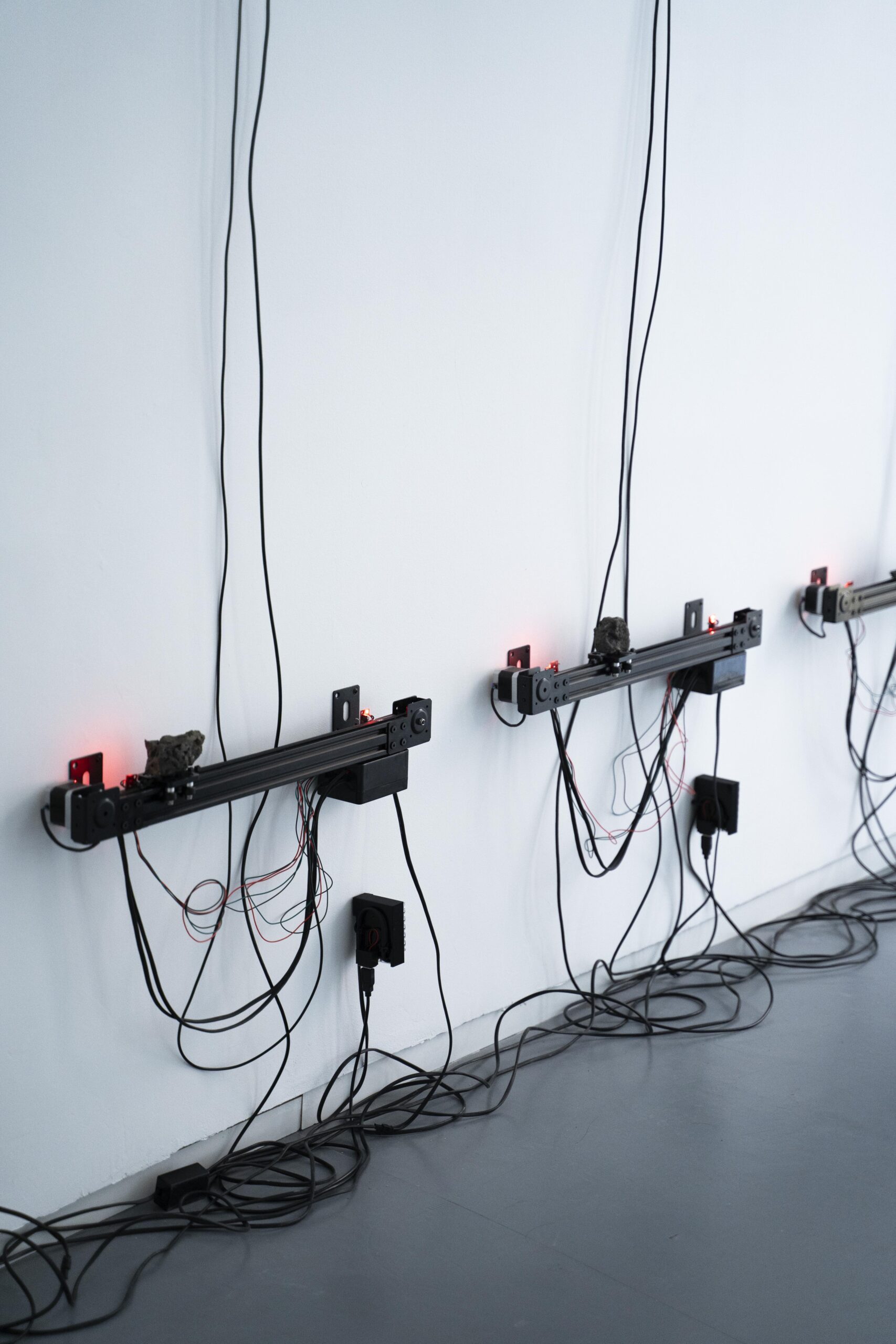

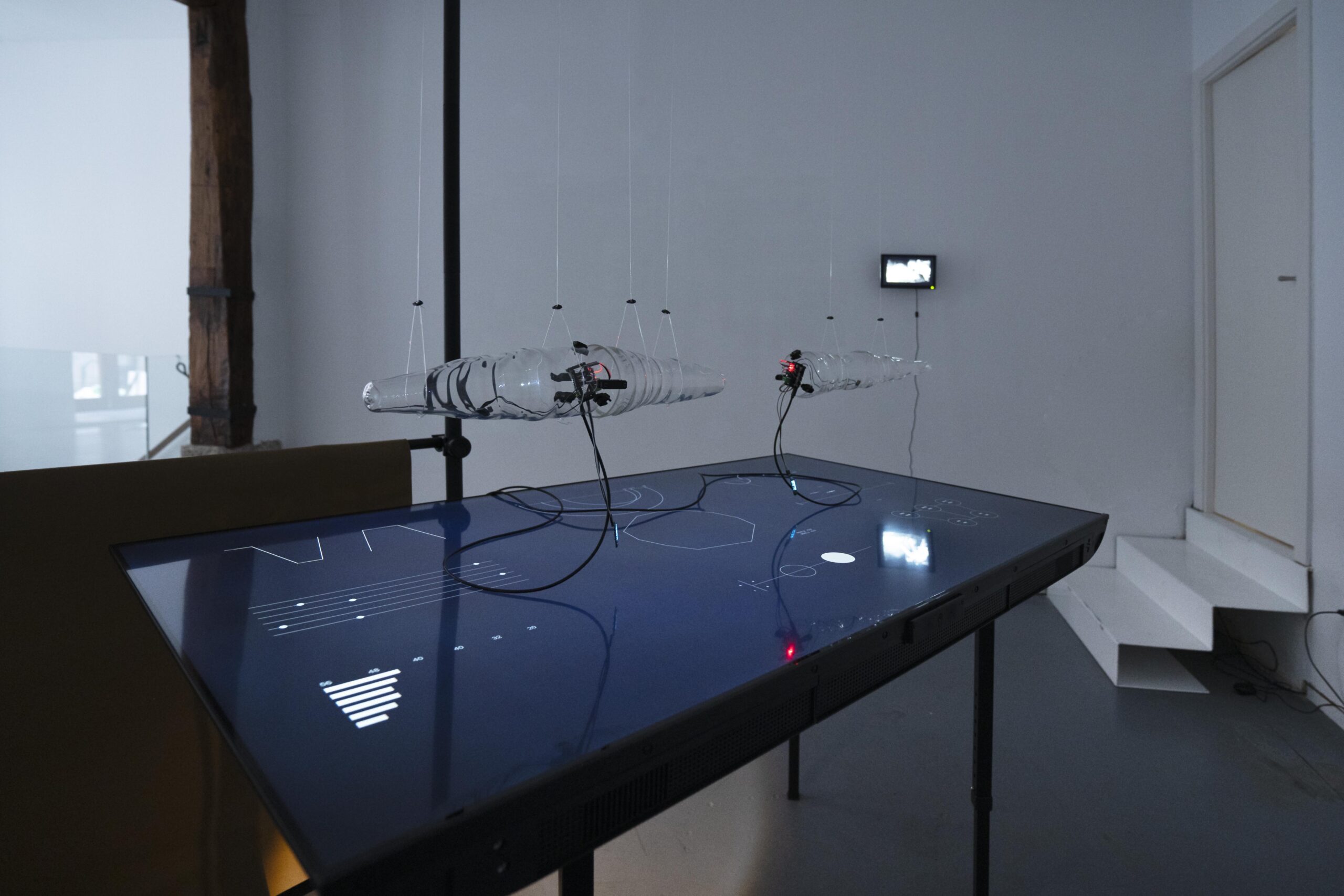

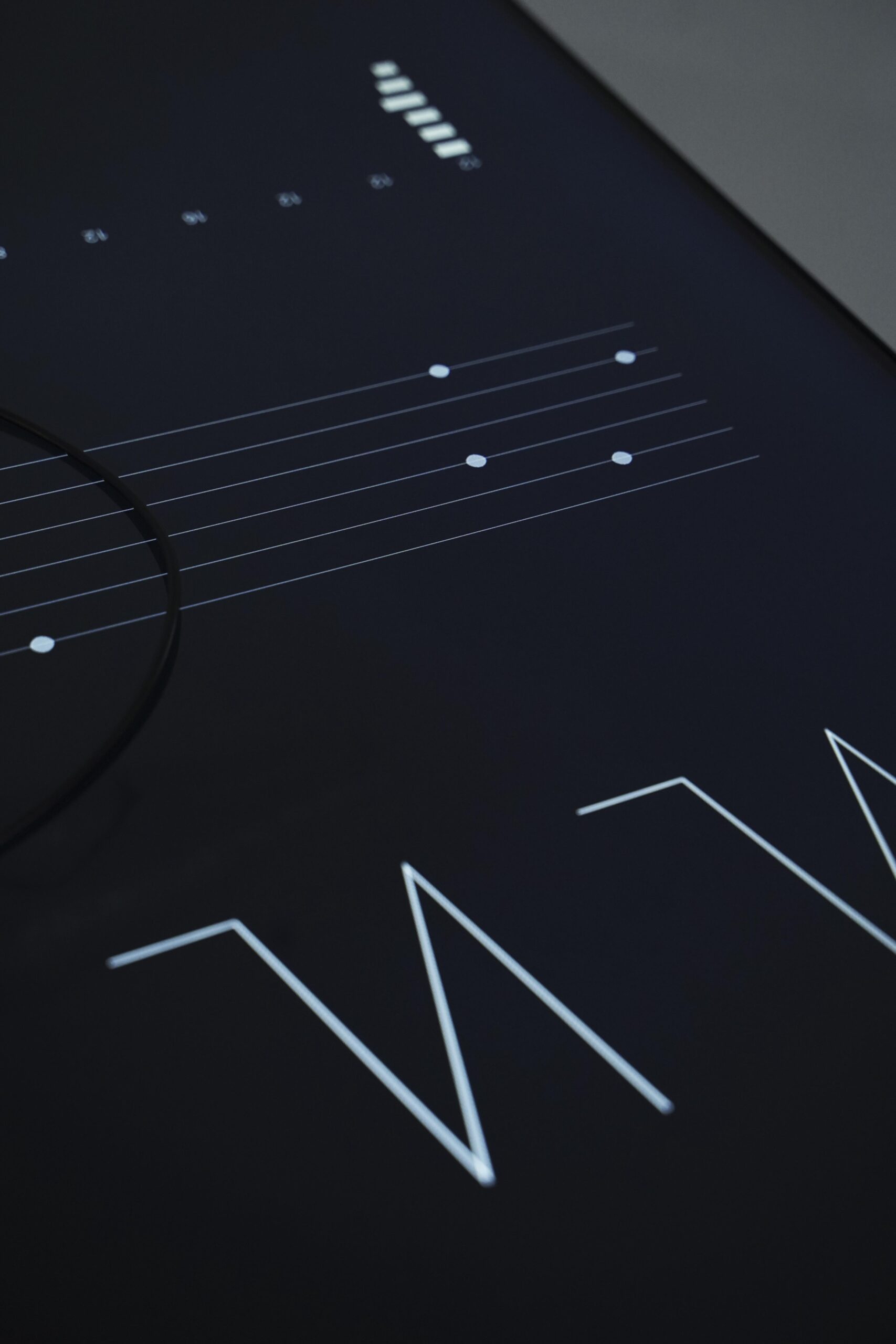

The first room of the exhibition hosts an installation that makes this process visible, by means of four screens connected to single-board processors and four rails on which pieces of slag obtained from the Roman mine of Cueva de Hierro (Cuenca) are placed. The computers detect nearby devices connected to the Bluetooth network and display the “raw” information obtained from them. At the same time, they activate the rails that move the slag pieces, thus reacting to the presence of smartphones and other devices carried by visitors.