Esta orilla es fruto is the title of Marina González Guerreiro’s second solo show at Galería Rosa Santos, and the first at its space in Madrid. For this exhibition, Marina worked with the idea of the orilla, or shore, as a space of accumulation and a boundary, a place where the concepts of time and matter are intertwined, a place where things collect. The etymology of orilla comes from the Latin ora meaning extreme, border or limit; and also, from the Latin os meaning mouth, entrance or opening. In this exhibition Marina draws a boundary that collects and harvests, but first she writes it in a thin line, like the water of the waves on the shore, producing a kind of corner or place. This corner is a fold, a trace that engenders objects and is depicted by its margins, like glossing a text. It accumulates material and is therefore material in an endless time where it ebbs and then collects.

The show begins with an installation comprising a number of materials that coalesce around the architectural structure of a stairway to nowhere. This imaginary construction accrues manifold meanings that come from the unhurried time of observation during the hours Marina spends in her studio. This architectural element resides at the centre of the exhibition’s visual narrative as an element of escape, circulation and also connection, similar to the knotted fabrics or other elements around the structure. Materials also accumulate on the steps, sparking a dialogue on the fragility and immutability of time. Each individual element becomes a fragment of memory and of experience, capturing ephemeral moments and prompting reflections on life itself.

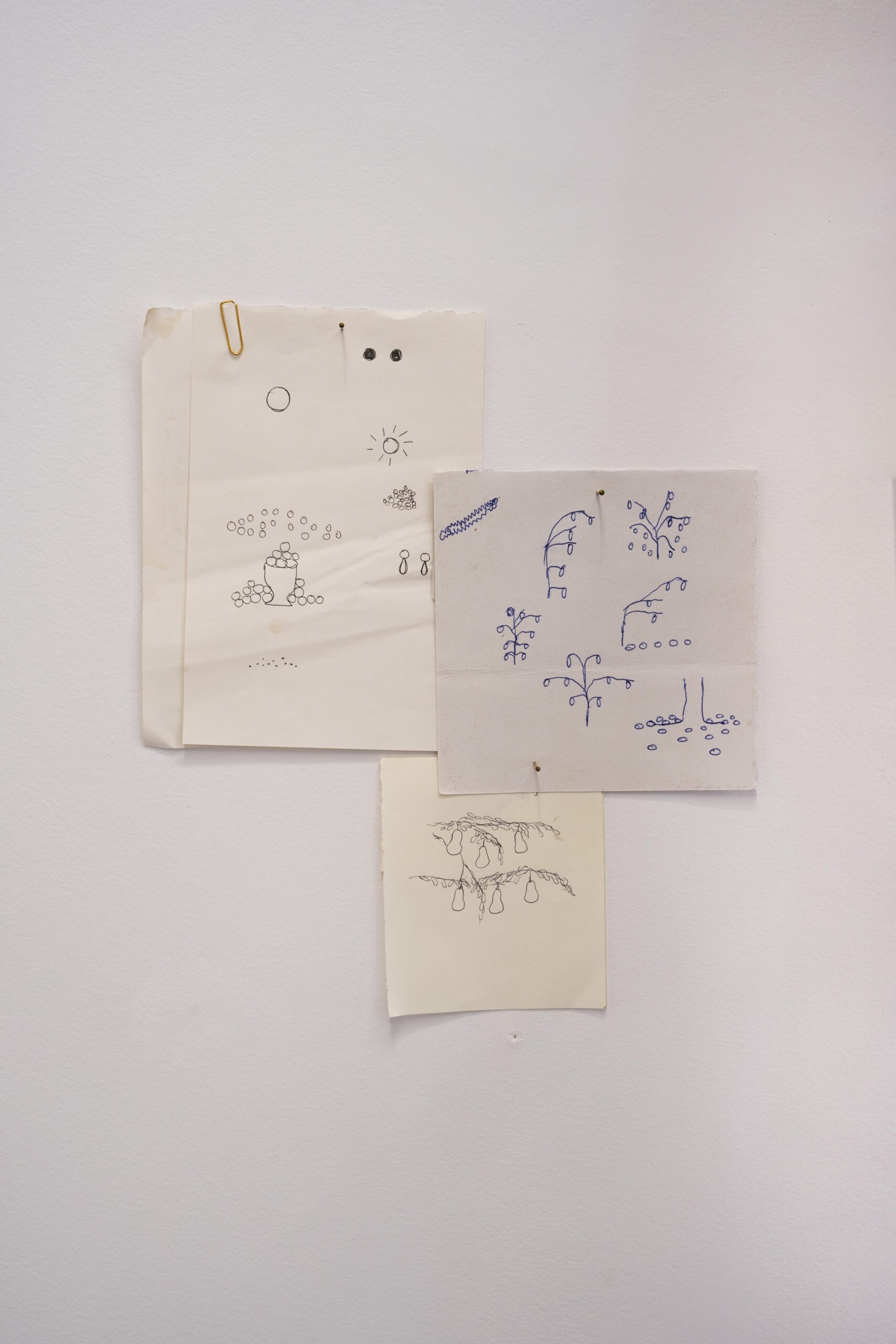

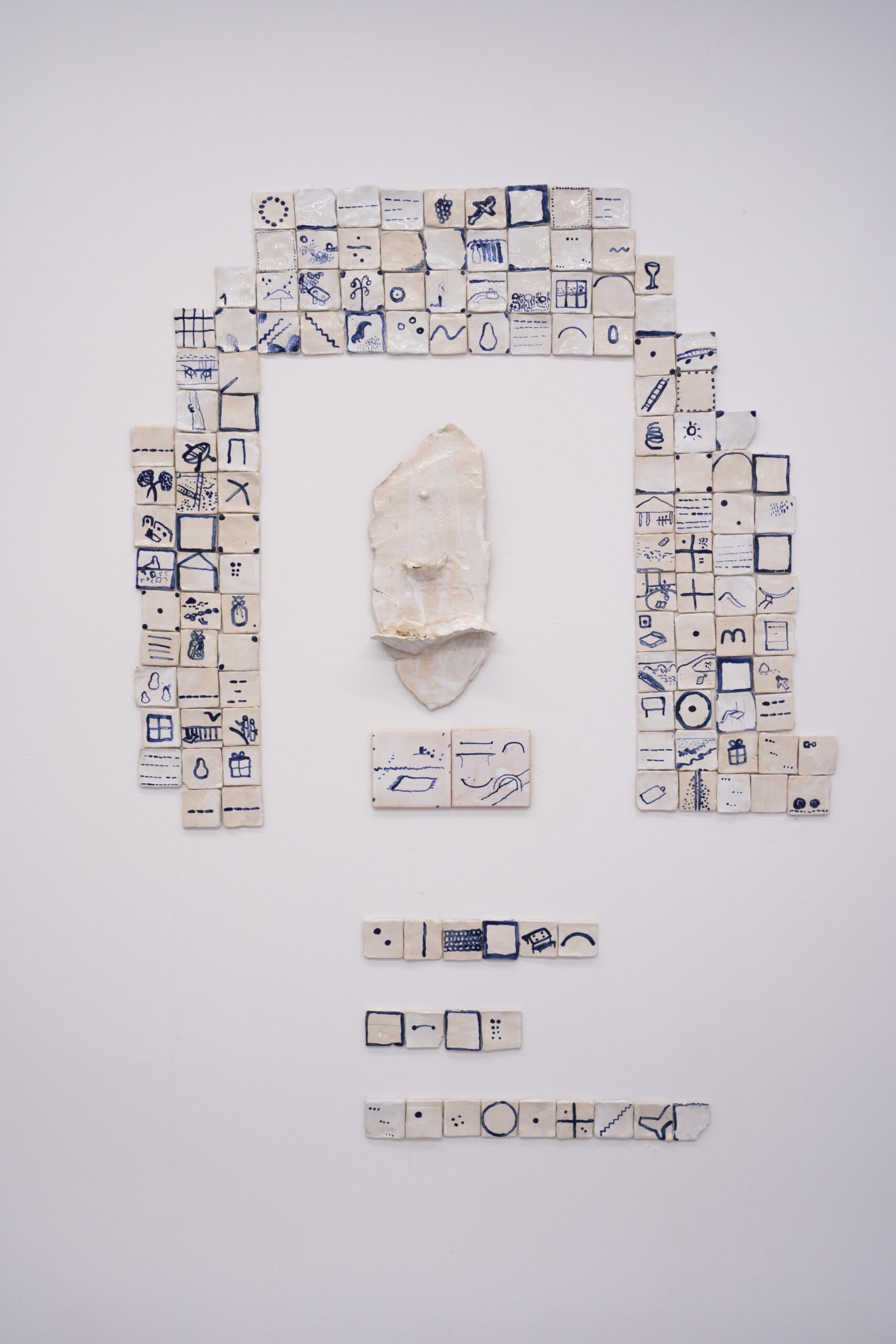

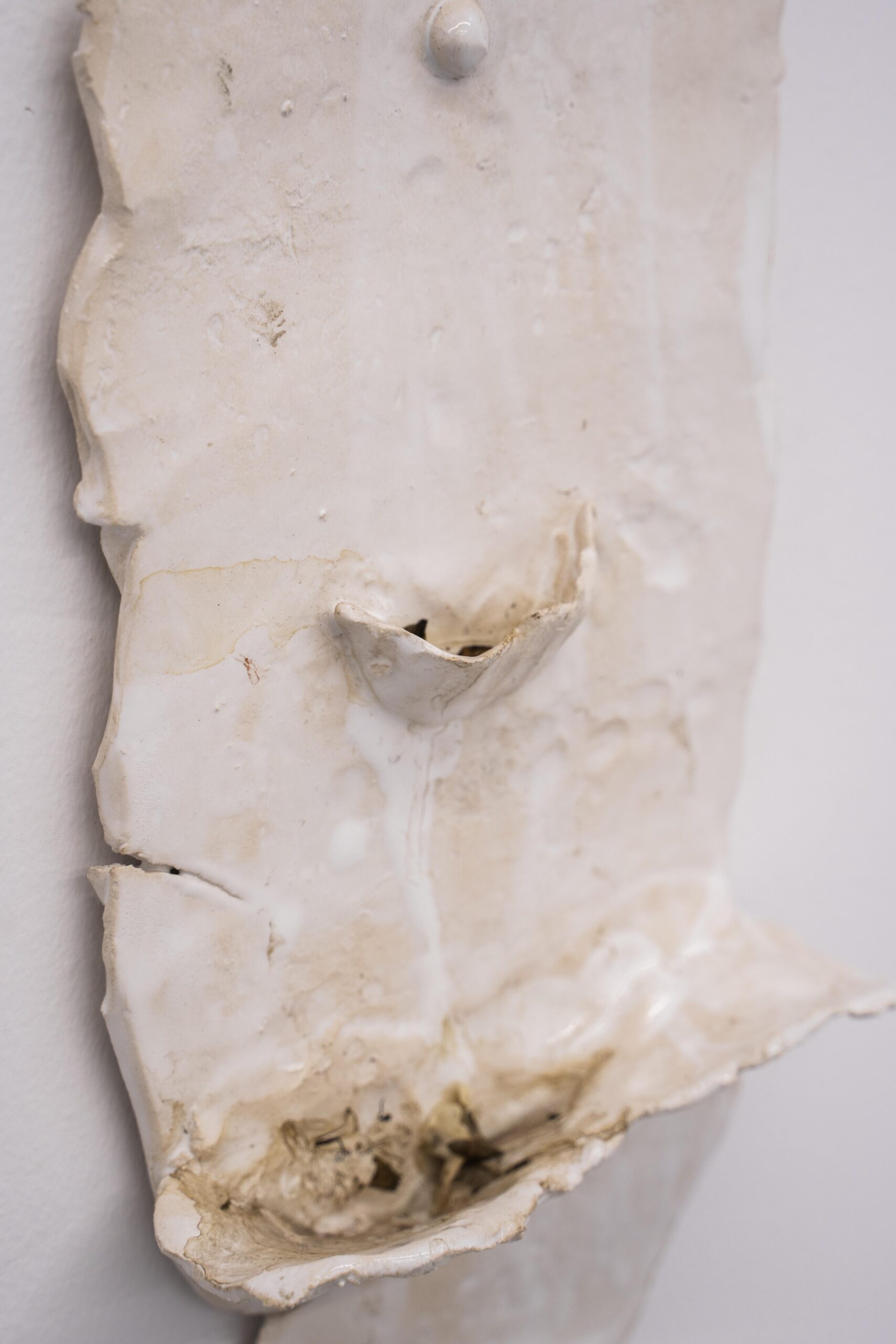

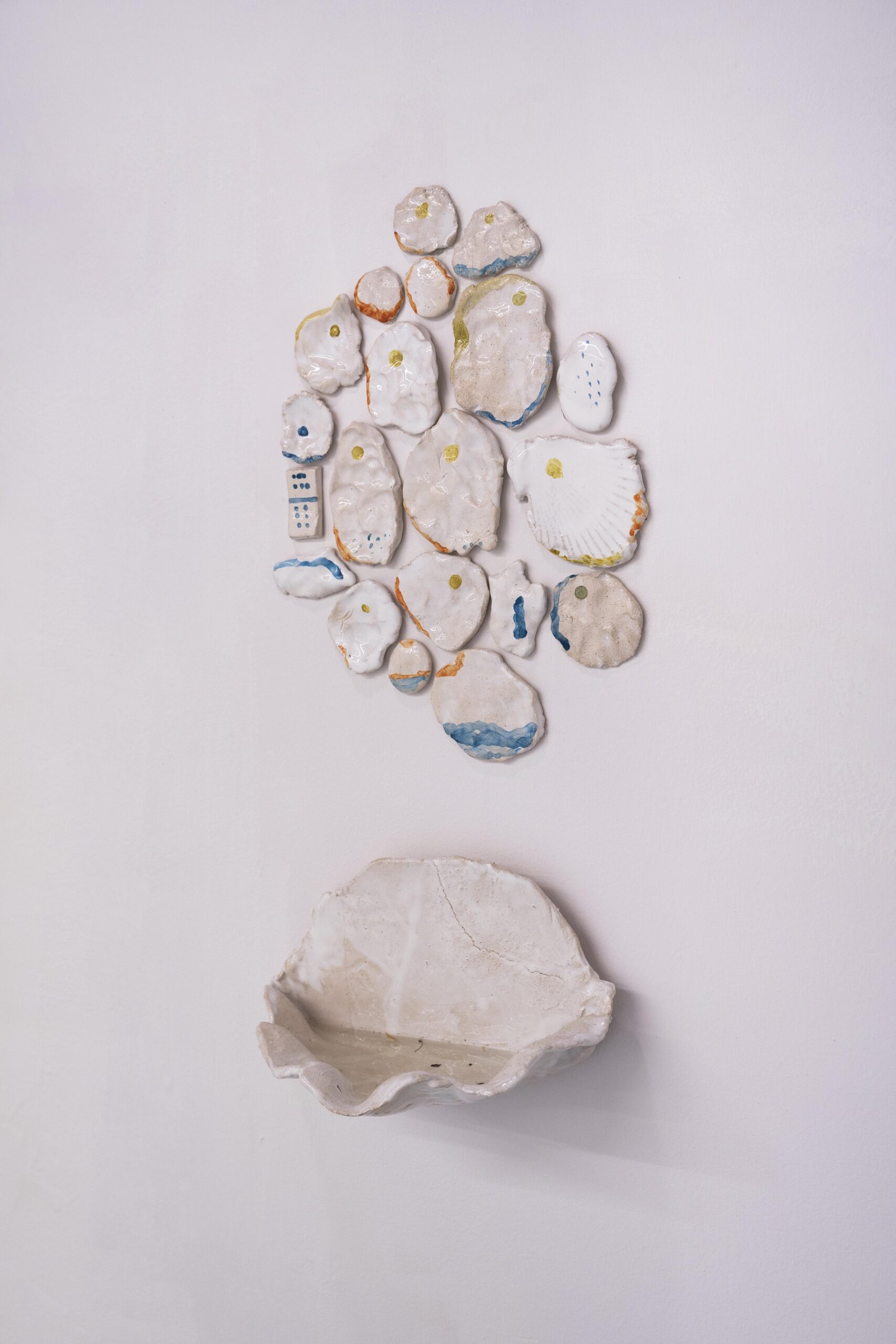

The structure of the stairs is rounded off by a series of small objects that are reminders of things that must not be forgotten. Notes, memory games and small tableaux composed of objects from the past or painted cubes conceived to fit into structures that in principle they are not made for. Her work as a sculptor focuses on fragility and the importance of the adaptability of the form, despite the variability of the elements she uses to construct her works. She lends great attention to the organicity of the materials she comes across, each taking up a particular place within her pieces, and susceptible to change or ultimately to decay. It is no accident that balance is always a core concern in her process of production, to the extent that there is always an interest in opposites—hard and soft, dirty and clean, and so on.

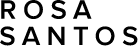

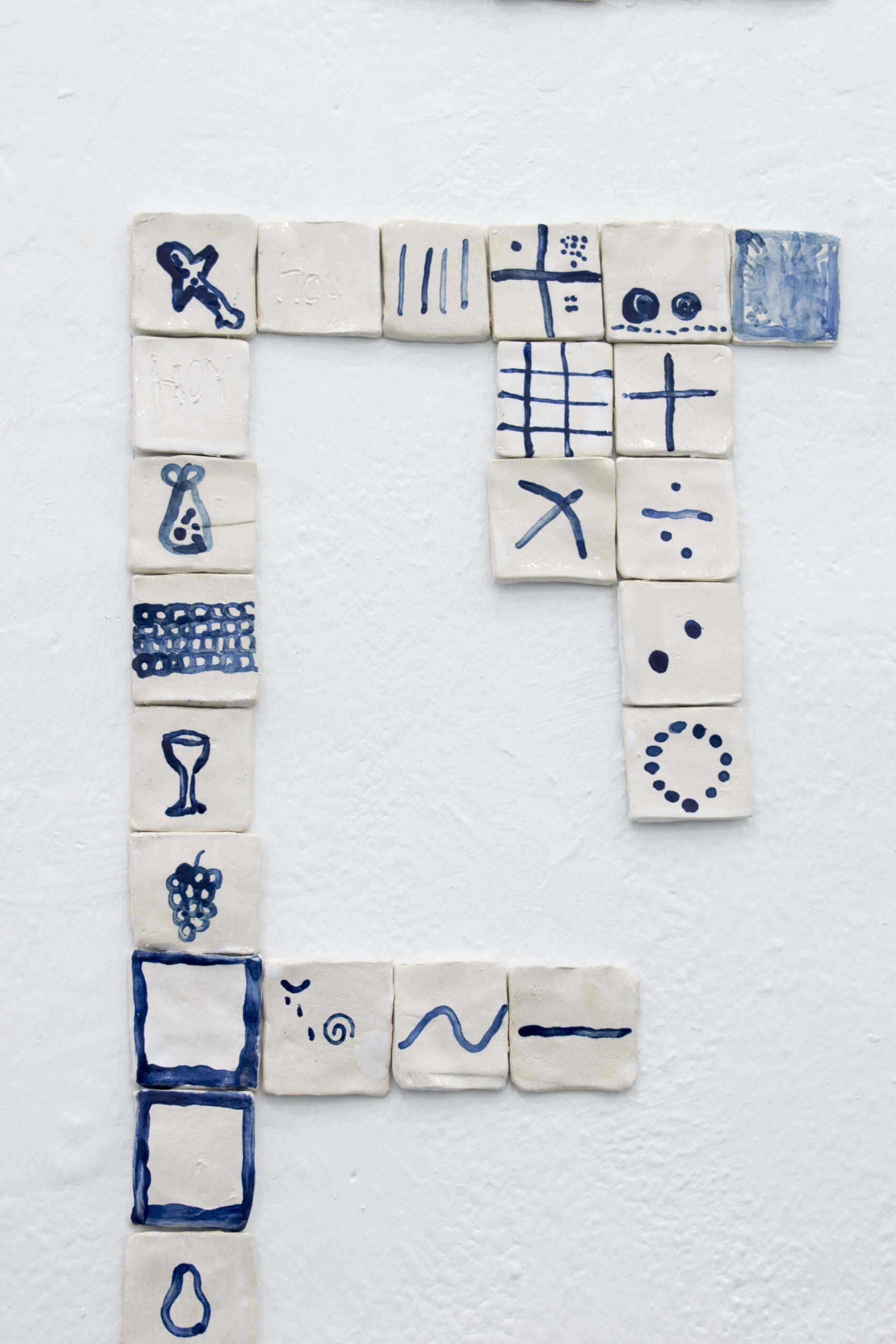

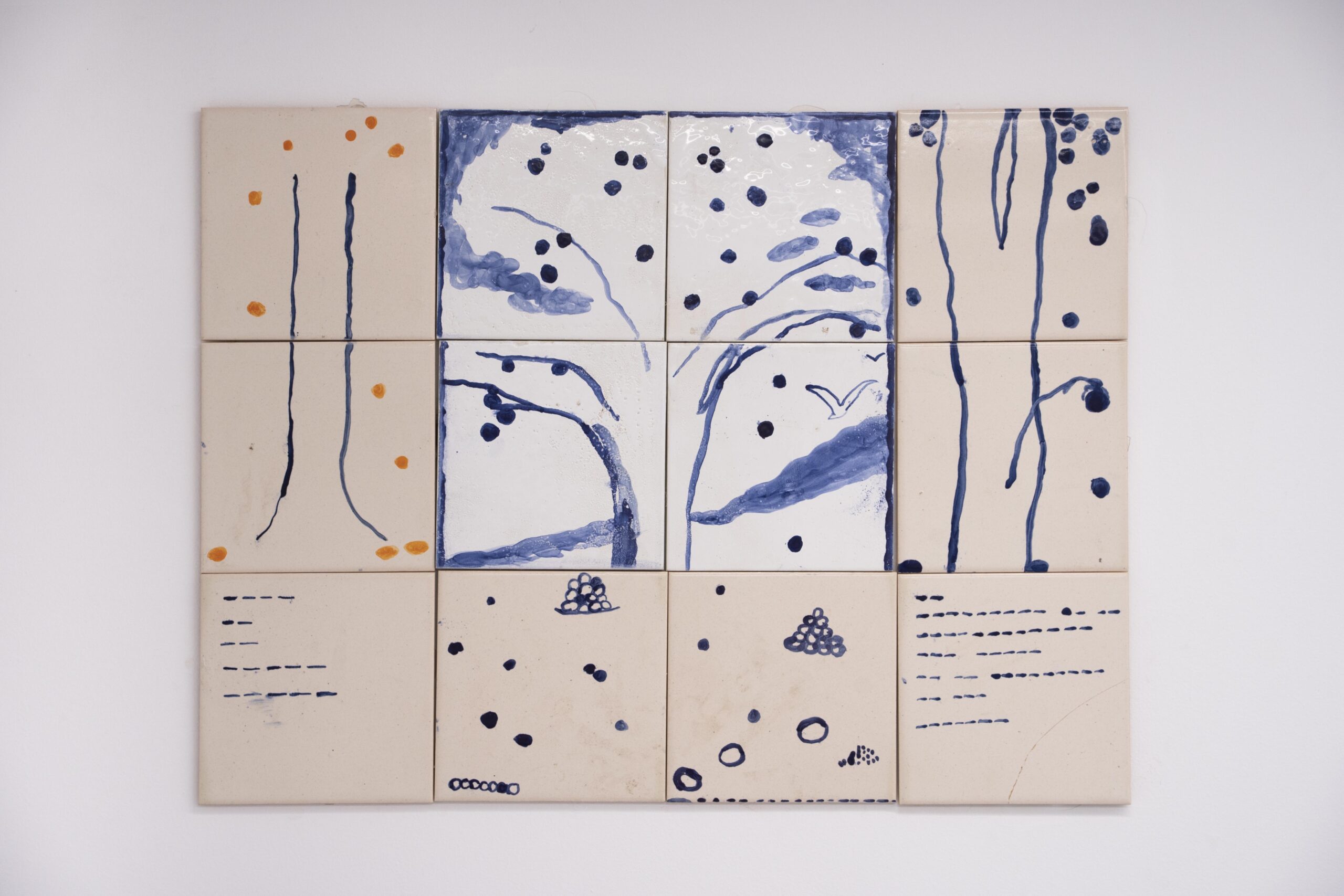

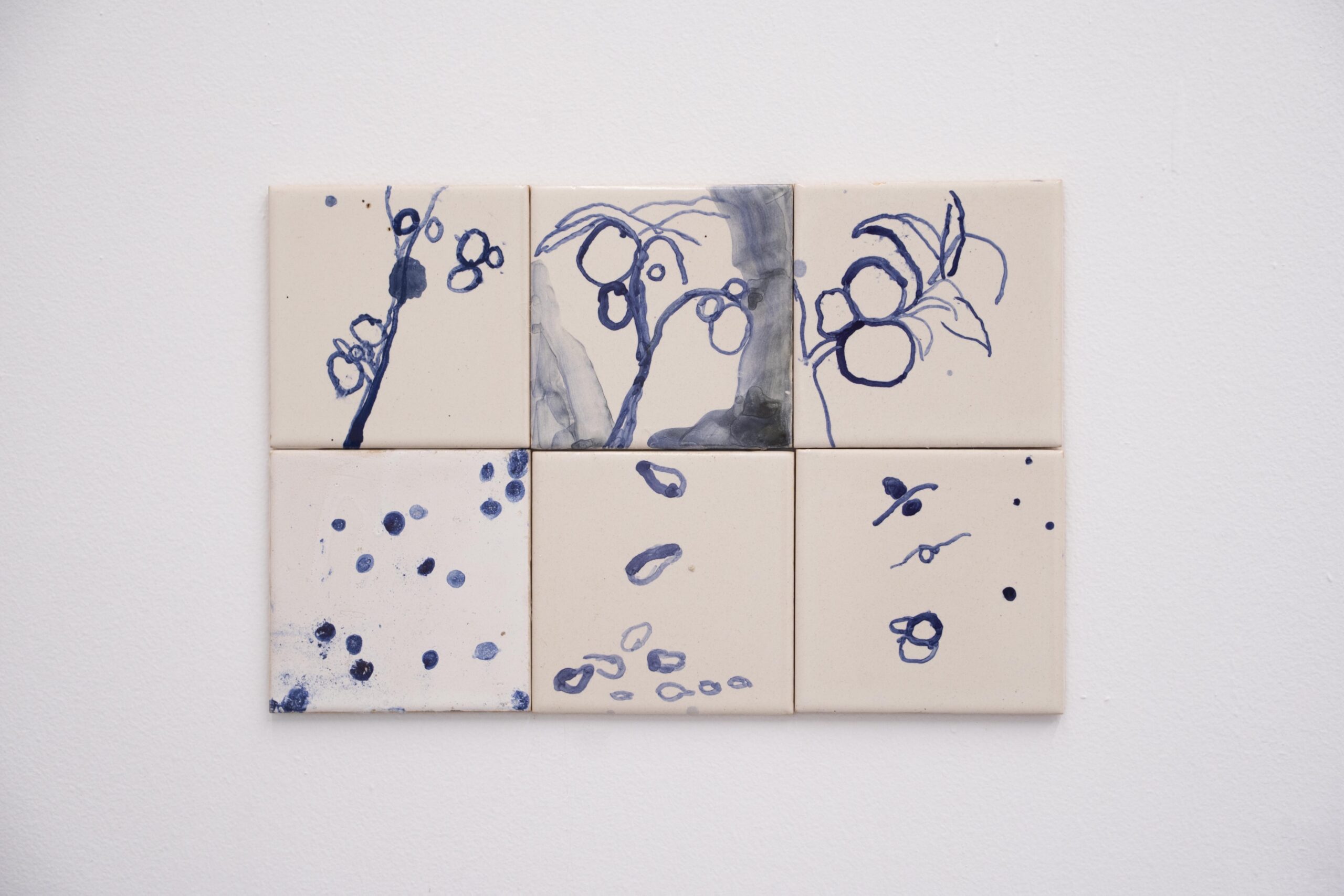

The oscillation between opposing poles to which she refers, makes an appearance once again between the evocation of the real image versus the abstract image finally accrued in the exhibition. On the lower floor, she constructs a courtyard with the tiles and signature water fountains of her personal imaginary. The coloured tiles covering the space operate as a kind of personal diary in which she represents a series of pictograms sourced from memories and desires. In her process of creation, Marina undertakes a personal exercise: she sits down to recall and transcribe her daydreams. She combines this process with life drawing in order to capture what is in movement and thus hold on to it. Her approach to this way of drawing is to write in images in a language she creates for herself whose pretension is to register the day-to-day like a diary. She produces an open-ended album with hundreds of files and documents that respond to a heterogeneous accumulation of narratives; or, the other way around, images that respond to narratives that represent Marina processing her memory and desires. The silhouettes she draws are always undone or unfinished, open to a search for another place. We find forms like plates that are clocks, boats, bridges or rivers: places of transit just like the stairway; and yet other times more concrete landscapes where the abundance of fruit trees stands as an image of harvest and celebration.

Emotions and stories in tangible bodies. In this exhibition Marina wants the narratives and the emotions to have an objectual capacity, links that will signify, connect and produce a reciprocity with the beholder. In it she explores the intersectionality between time and perishability, and there is an evident intentionality to accumulate it, give it away and share it. Here she opens up a path to other forms and materials without losing the connection to her past works, as she continues to sort things out and put order on them. And she ultimately renounces time like when Simone Weil wrote that: time is an image of eternity, but it is also a substitute for eternity. And so she continues.

Paula Noya de Blas

Simone Weil, Gravity and Grace. London and New York: Routledge Classics, 2002, p. 19.