Every beginning is contingent on an ambiguous event. When it takes place, one can barely intuit the direction or form it will take later. Whether it will last (if it is indeed the beginning of something), or whether it remains in a mere semblance of possibility that goes nowhere, an isolated act without any future. Nor is the end free from this same ambiguity. Every farewell is accompanied by a double track that will only be clarified further along: is this goodbye an end or, on the contrary, does it contain within it the seed of continuity? The answer will be renewed in one way or another, either with a reencounter or an absence.

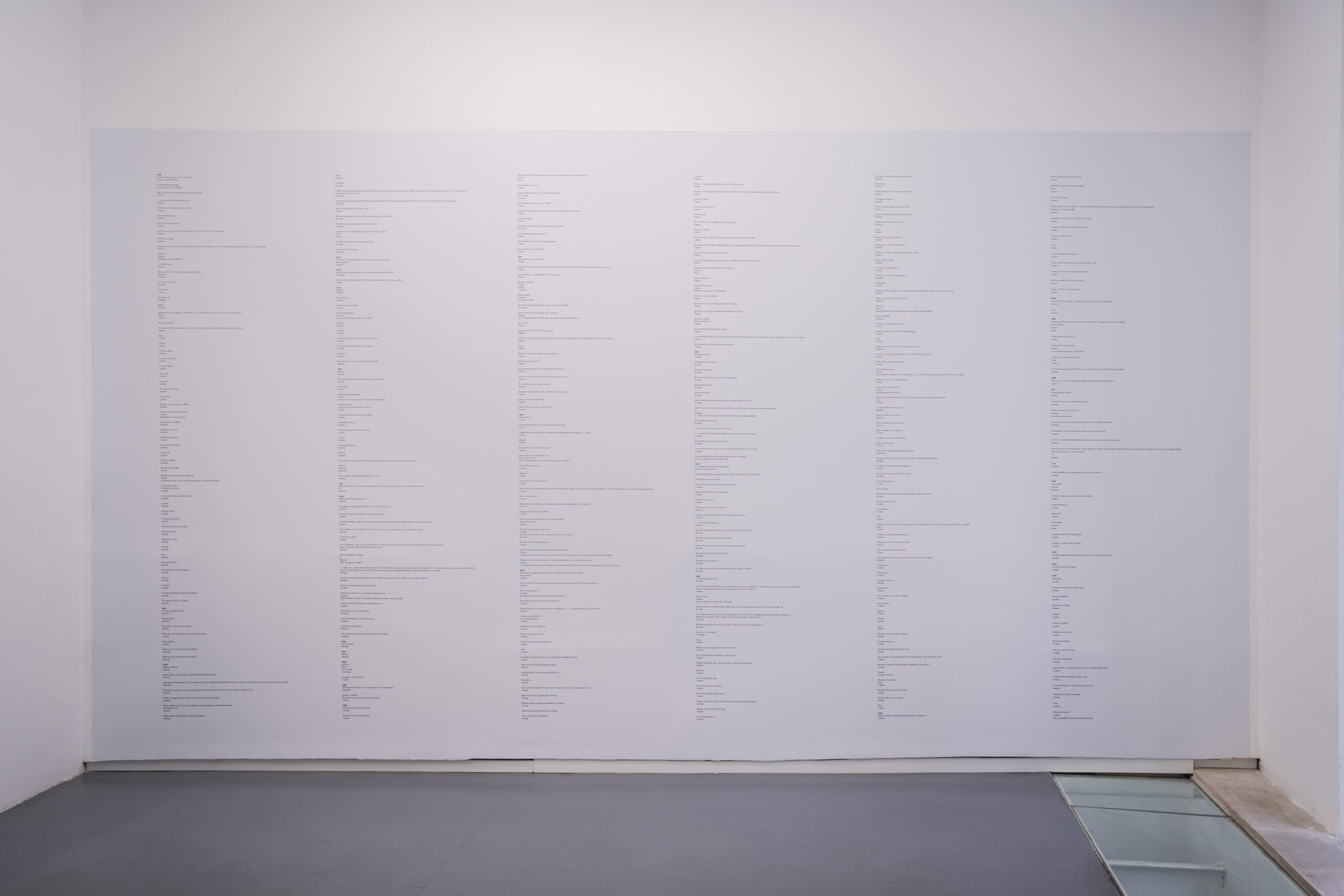

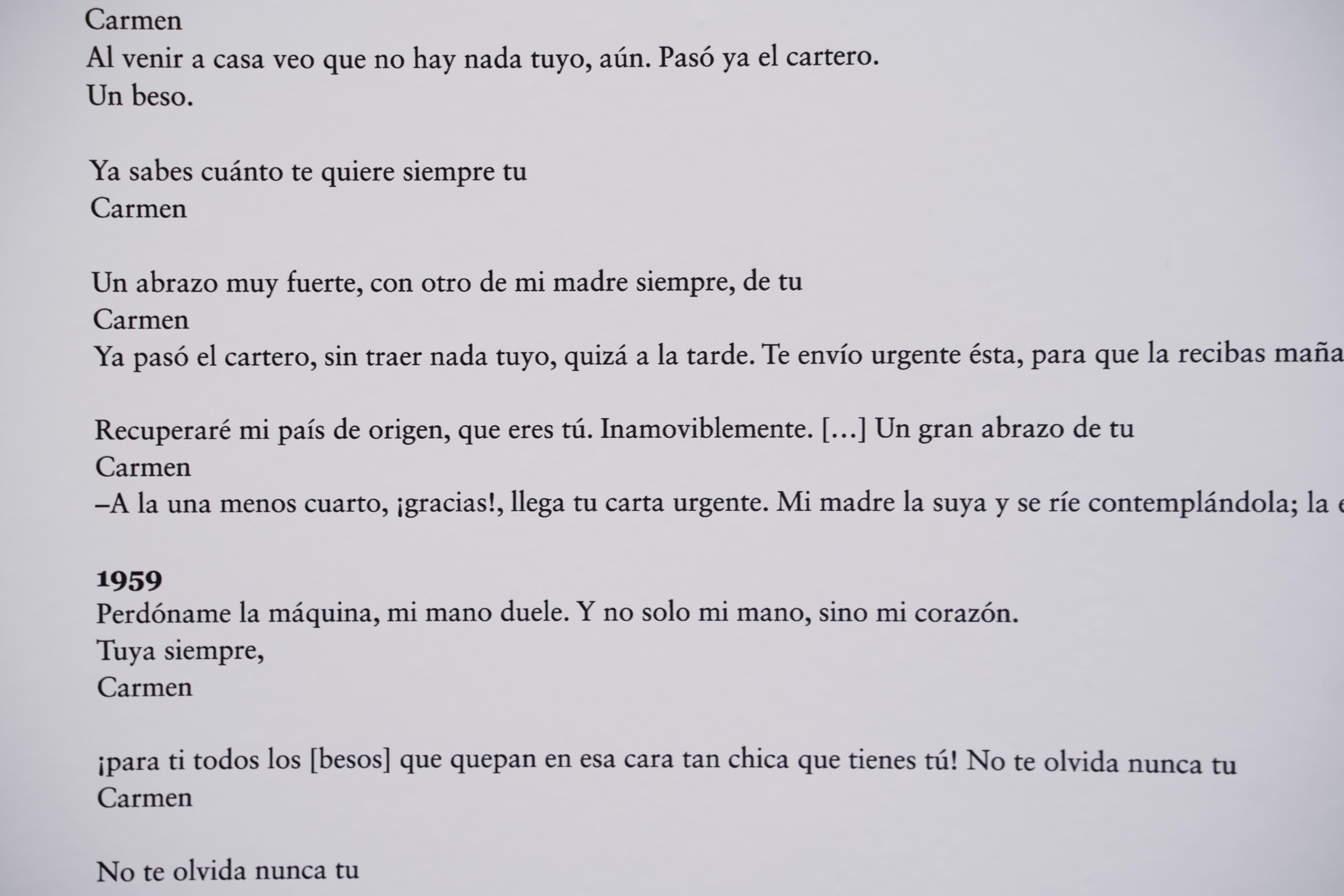

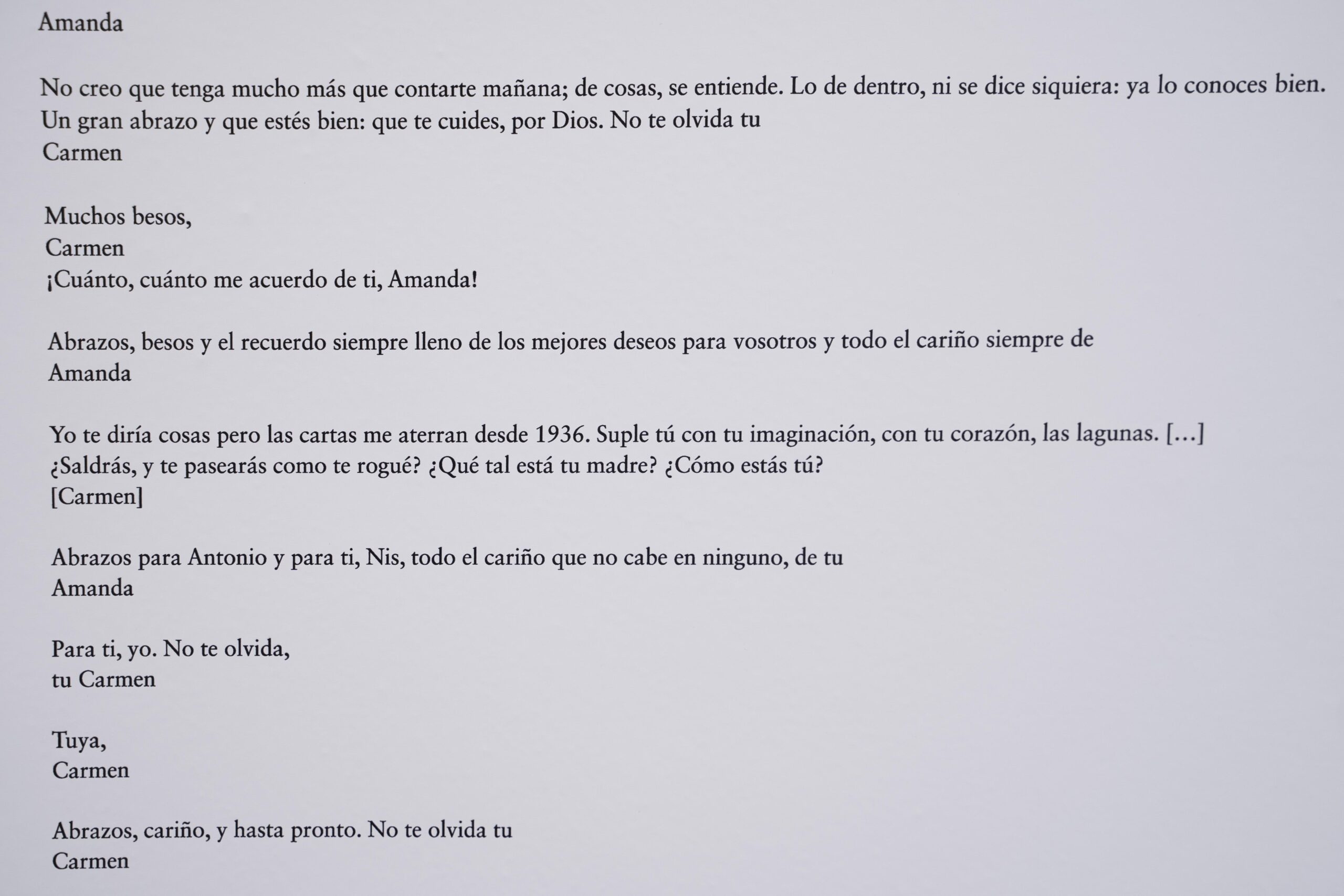

Every leave-taking, like every beginning, is an exercise in guesswork. When bidding farewell, the dialogue adopts the rhythm of distance: a conversation is postponed, held on pause in the face of the void to come. Perhaps owing to this void, written goodbyes produce an echo. In Abrazos, abrazos (inamoviblemente) [Embraces, Embraces (Immovably)], María Tinaut summons Carmen Conde and Amanda Junquera through the written word. Floating over the course of forty-two years of correspondence is a desire to continue after each signing off. At heart, this work addresses absence as an intimate place that the word never manages to verbalize, since there are letters where presence is missing. Between the lines, an inexpressible light and eroticism spring from this silence. There isn’t enough postage to send so many embraces and so much love to its destination, and yet I imagine both Carmen and Amanda remembering their respective longings for a shared future, breaking the scale of linear time of the possible. Carmen Conde asked: “From where does it come this glass of silence, and this cold, and / this emotion of distance?”, and she did so before they met. Like on the blank sheet of paper, on the whiteness of this wall the word becomes image; this is usually the case with any writing that moves us: by leaving a trace, it itself becomes that trace.

Indeed, in principle a farewell is only the potential of farewell. It was the month of September when Kafka wrote the following in his diary: “the farewell letter is ambiguous, like my feelings.” Ultimately, how is it possible to continue when you don’t even know whether something has finished or not, whether you are on the verge of drawing to a close or of setting out. If there is no continuity, how can you go on? Perhaps by going somewhere else, at least moving what is close at hand, bringing about a change. This is what happens in Y cuento contigo para el amanecer [And I am counting on you for sunrise], a work from a series Tinaut begun in 2021 based on hand-dyed and mended mattress covers. Apart from an experience of distancing and rupture, the shift from the initial diptych to the lone work suggests a reaffirmation of the individual body. When observing the extent of the fabric, patched with stitches, I am brought to mind of a note by Canetti that María might recall: “if you have seen a person sleeping you can never hate them again.” Lingering in this blue inclemency, mounted on a stretcher, is an outpouring of tenderness, a vulnerable and sleepwalking desire.

The day María shared with me a quote from Jeanette Winterson, I answered through Simone Weil:

– Why is the measure of love loss?

– Why is it that so soon as a human being shows that they need another human being, either a little or much, the latter draws back?

Though they are written on paper, some questions remain floating in the air.

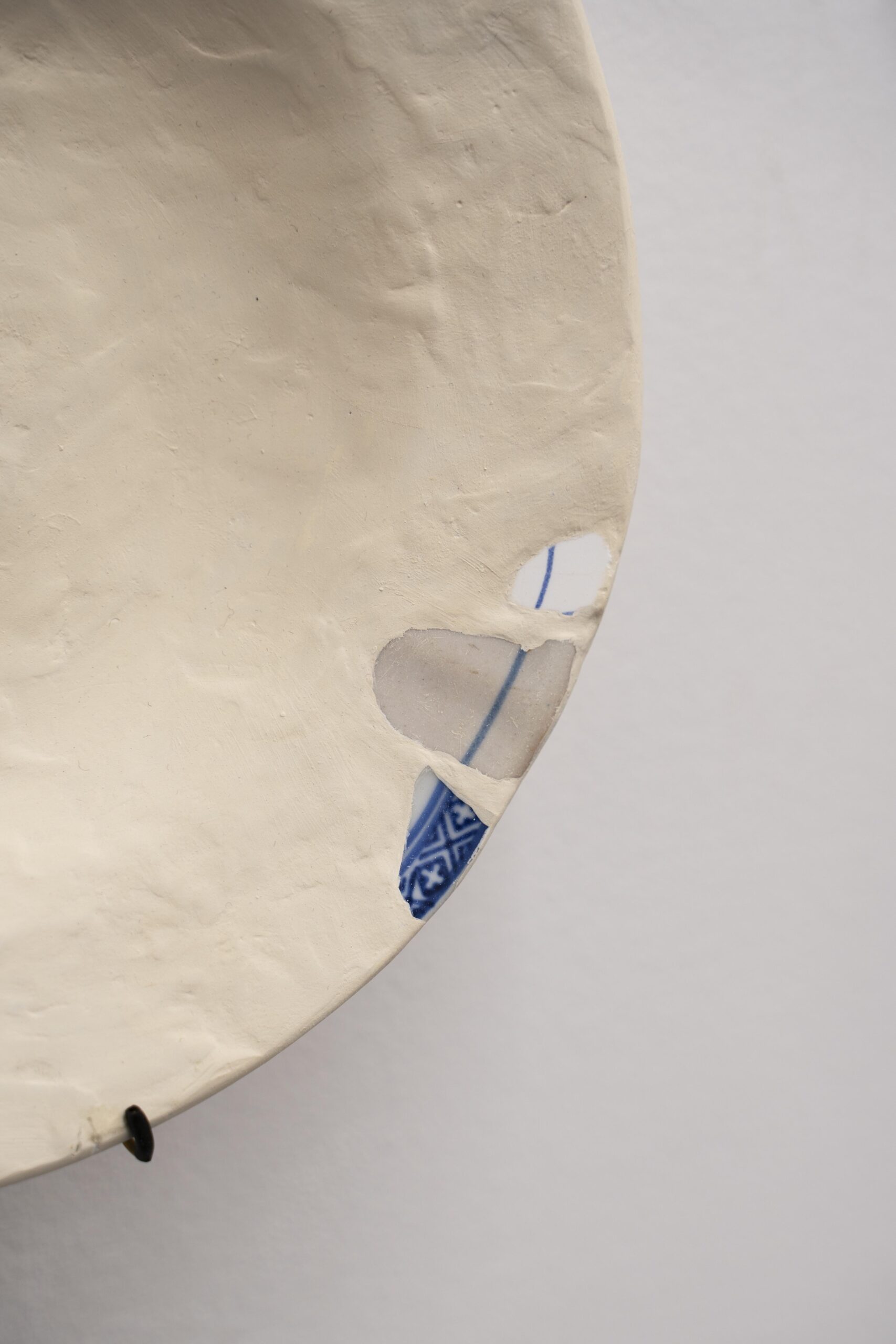

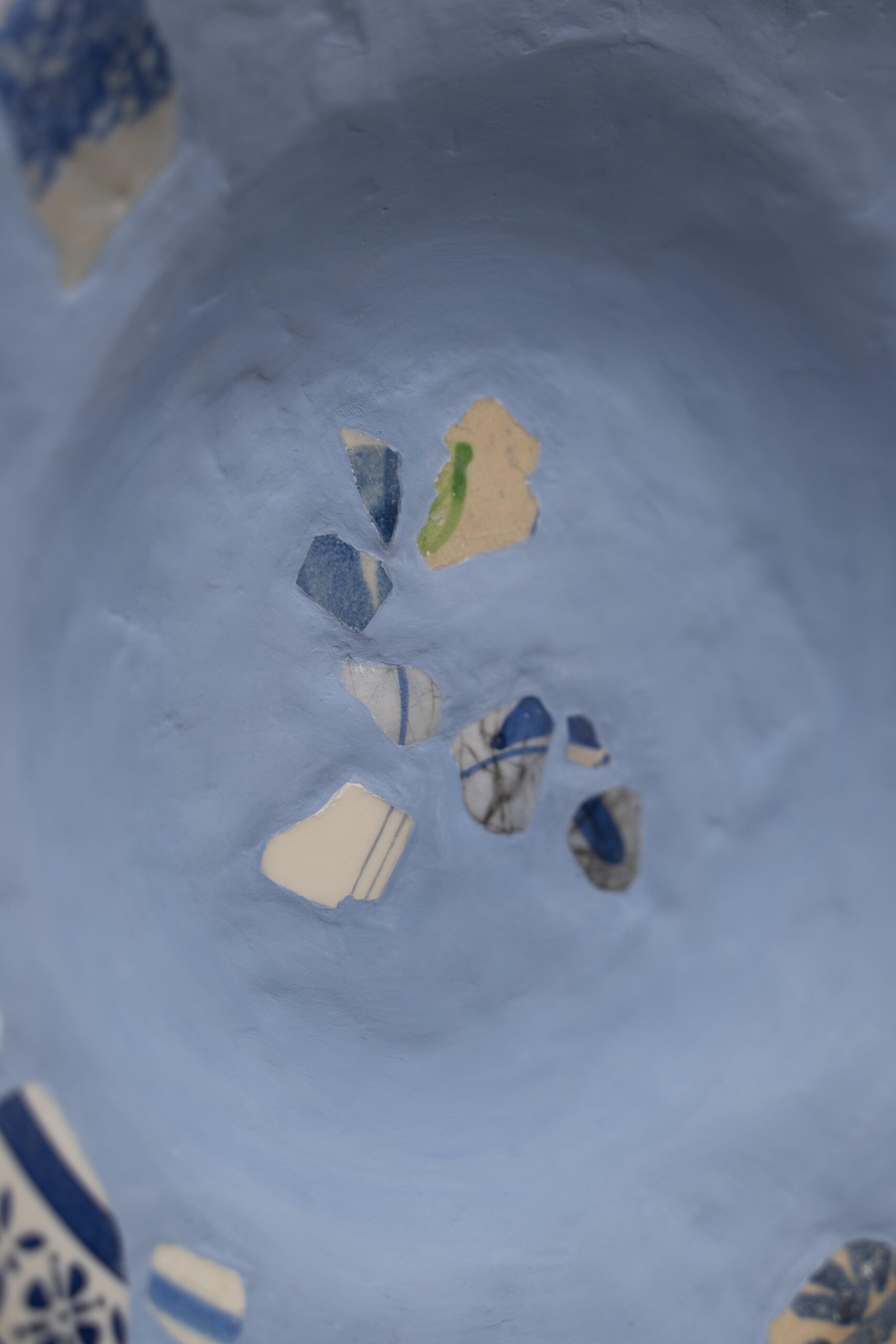

I spotted some fragments of ceramic on a dirt path that fitted together, separated by millimetres. I walked on by, and when I returned the following day to pick them up, I only found one of them: a beginning and a farewell. Another time, at the beach I plunged my hand into the sand under the water. Probing about, my fingers touched bits of broken ceramic; I took them out one by one until I wasn’t able to hold any more in the palm of my hand. The enamel, white with the odd touch of blue, was cracked. Years of erosion had smoothed the edges. What can you do with the grief of the broken? In the three reconstructed plates in Untitled (blue again) I, II, III, María Tinaut tries to return the fragments to a shared yet impossible state. We do this at times: whatever it takes to bring something back to life.

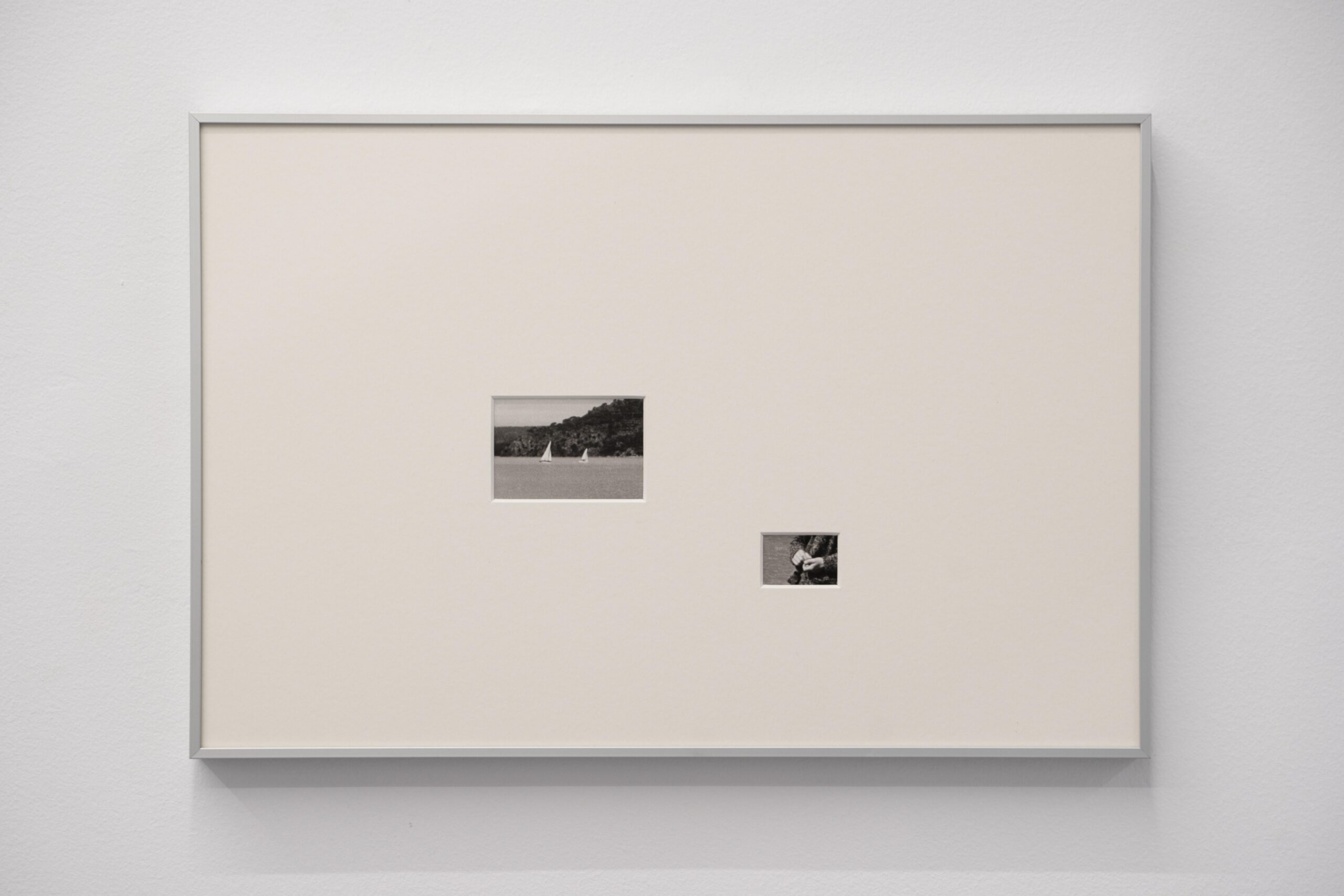

For Jean-Luc Nancy, “Sleeping together comes down to sharing an inertia, an equal force […] drifting like two narrow boats moving off to the same open sea.” I’m not sure whether it is true that there is more inertia in a drifting boat than one with a steady course; I sense ambiguity in El mar, aún más cerca [The sea, even closer]. The image of two boats pulls in the gaze like a gravitational force, but it is the two hands that I keep going back to. They are even closer, though I don’t manage to reach them; I make gestures with my hands but they are useless on land. Like a conjuring trick, this piece is the product of concealment. Both fragments, boats and hands, hold each other in suspense thanks to the blank space that paradoxically separates them. By dividing the underlying photograph, the image is multiplied, and I return to the sea: in the fragmented sequence of what is left, two boats almost touch, but to endure they never meet.

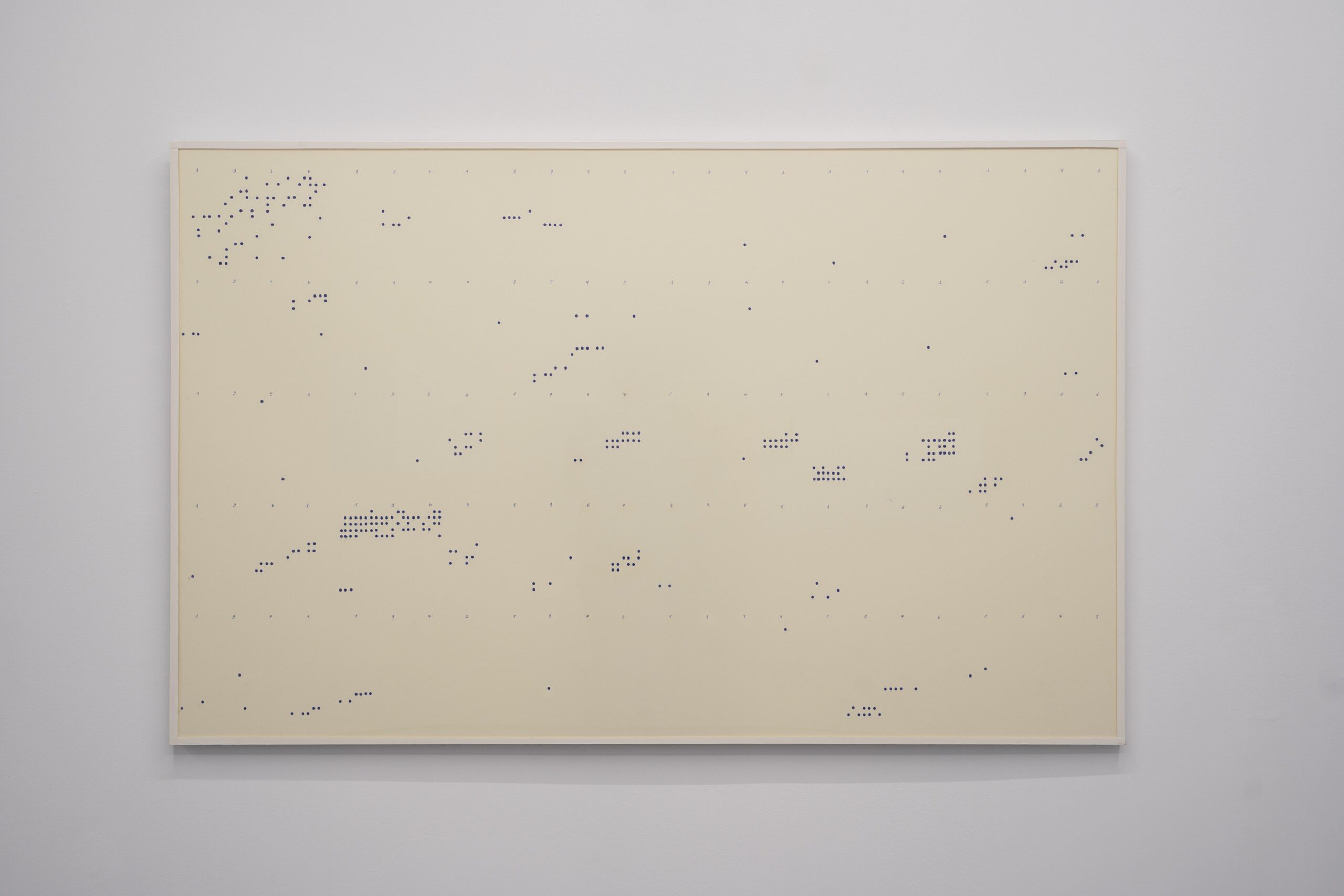

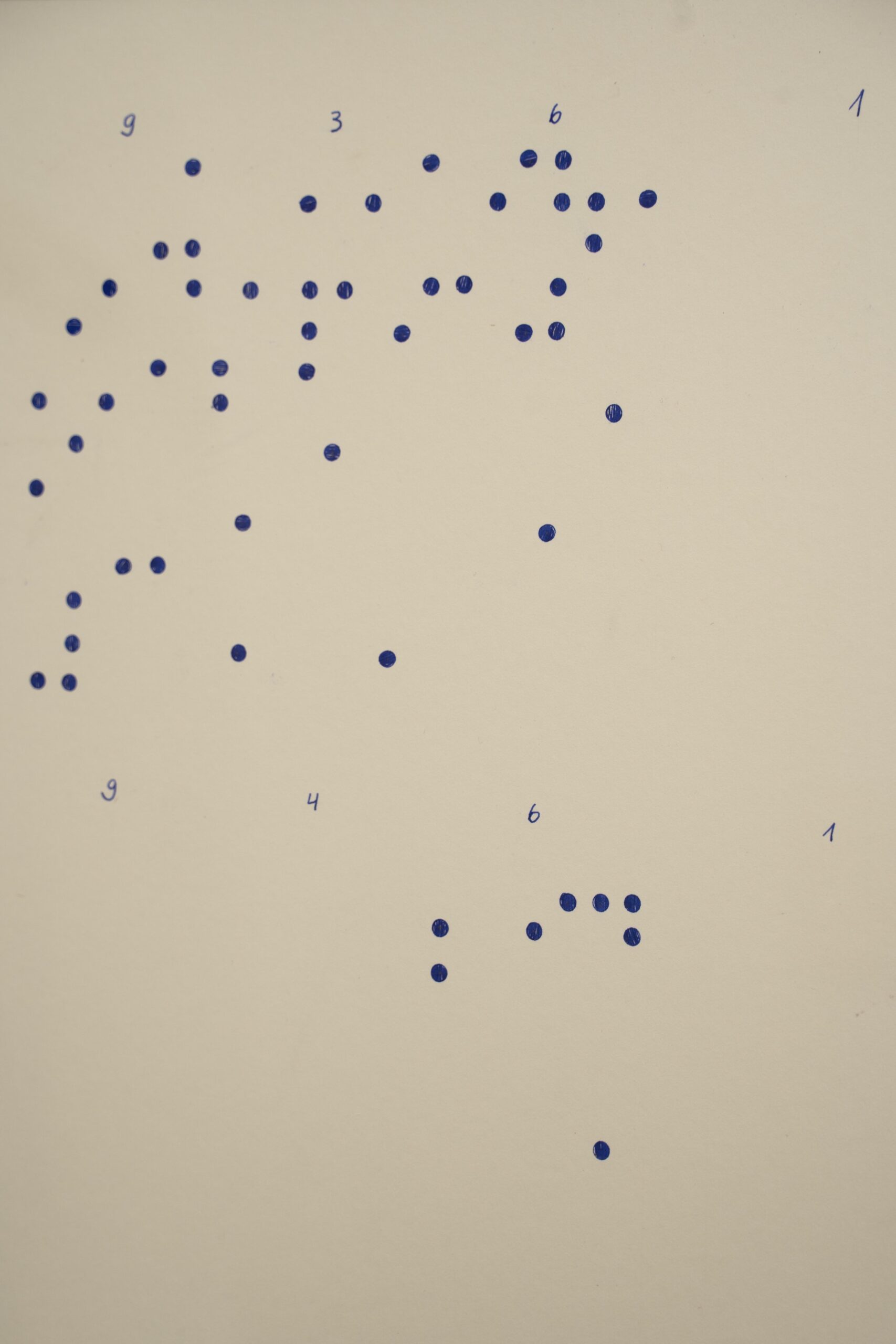

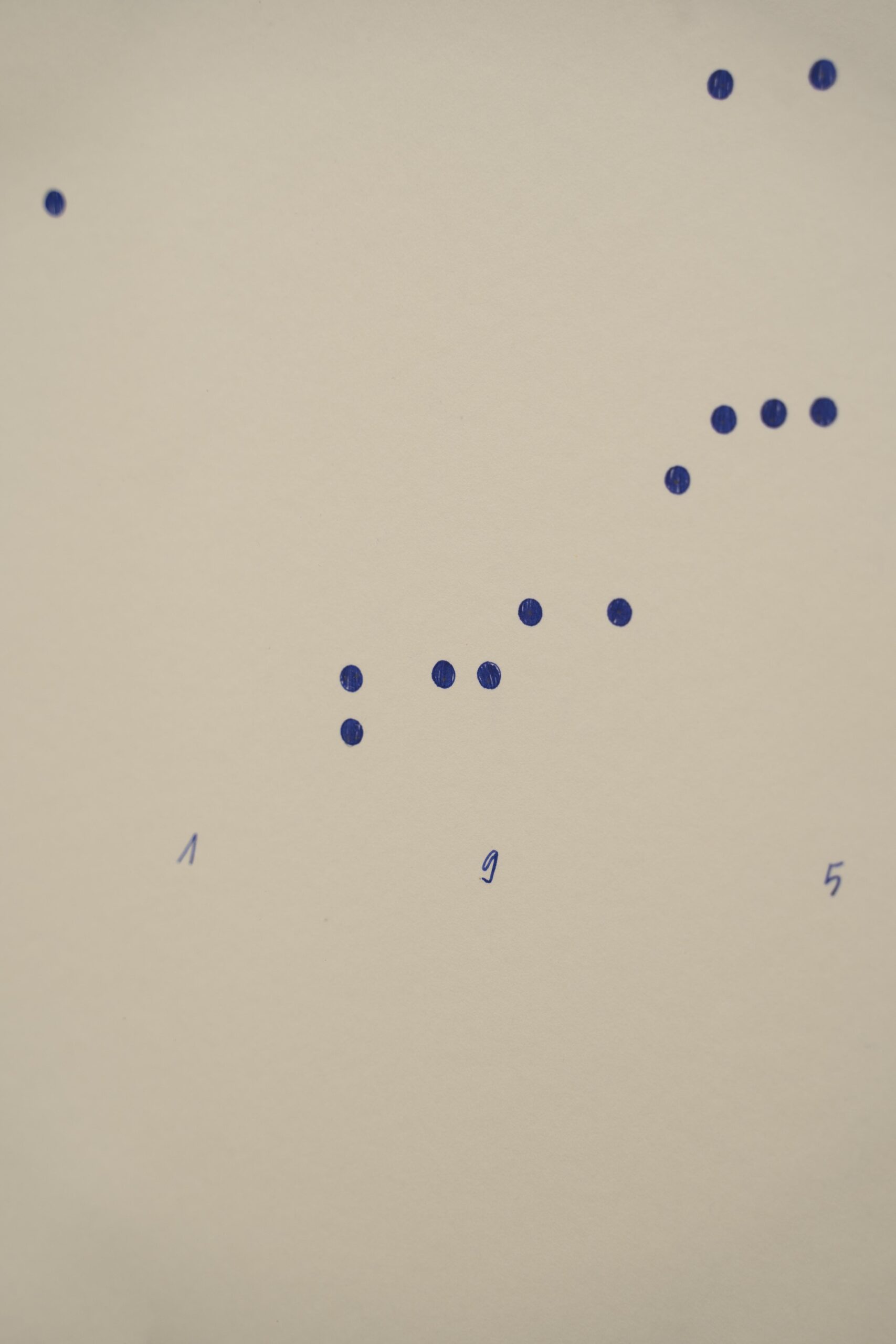

My eyes leap from one detail to the next, I try to fill the gaps but I also take away with me a void. Like a secret constellation, Tu imaginación, tu corazón, las lagunas [Your imagination, your heart, the gaps] is the trace of a calendar of echoes, of welcomes, of waitings. September is perhaps the month of farewells. There is separation, maybe an exile, perhaps more of a bereavement. I am reminded of Clarice Lispector when she wrote that she only worked “with losses and discoveries”, because this is also what happens here. and September’s clear and blue again embraces and then, after a certain point, releases and lets go.

Laía Argüelles Folch