Following the parcours, in the following room we come across some small collages in which we can identify images of the Mies Van der Rohe pavilion in Montjuic, Barcelona. This gem of modern architecture, and an example of a language that regulates and orders the movement of bodies in a space, is also a building whose surroundings have been gradually taken over by other corporeal choreographies. Cruising could be defined as loitering with erotic intent, a universal practice in the Western urban world that defends the culture of sex in public with the purpose of sustaining the pleasure of immediate carnal contact within contexts of persecution or marginalization. It ought to be understood as a collective strategy to appropriate the streets and take over the city (the public space), as a way of creating community for those who do not have a community (who have no space).

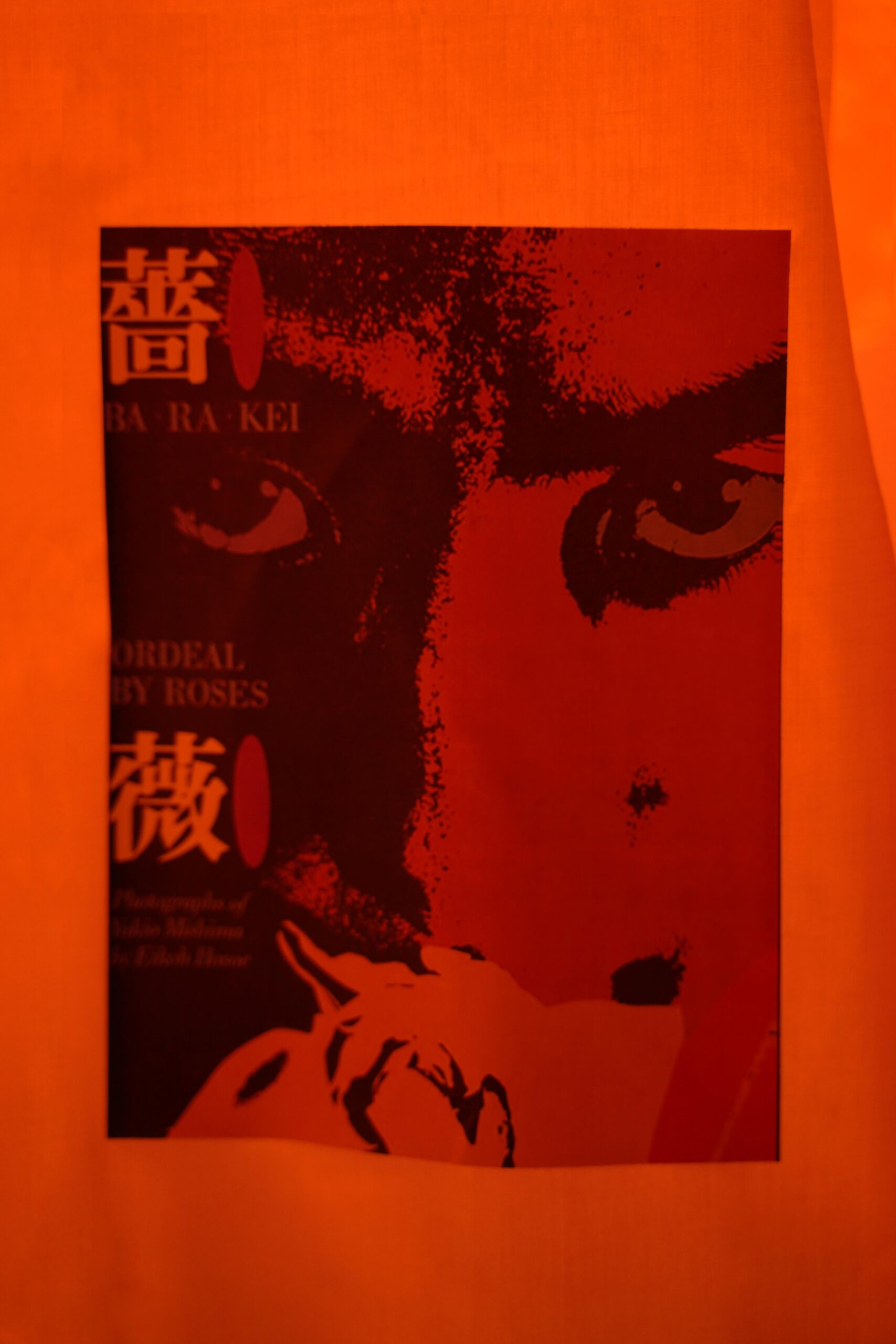

Jose Estebán Muñoz’s theoretical work Cruising Utopia serves as a framework for many of the reflections undertaken here by Miliani: the need to open up new horizons to create other communities grounded in dissident politics; intimacy as a clearly political gesture; utopia as a projection of the future. That being said, confronted with the present continuous of the term ‘cruising’, we are faced with a continuous reactivation in the here and now. This makes us think of something interesting and leads us to believe that the past does not exist as a closed block, but, on the contrary, as a constellation of traces in which the key to open the door of a future of healing, where all bodies can exist, may be hidden or momentarily deactivated.

The work that gives its title to the exhibition is a textile piece, a rug of sorts handmade by the artist’s parents with a multicoloured text that depicts the onomatopoeia AAHH, an expression which could express a feeling of surprise, acknowledgment, pleasure or pain depending on the situation. This space generated by an absence of context pulls us through a crack in the strict normative of language. Viewed as an anagram, AAHH also encompasses HAHA, once again embodying the same ease of turning one thing into another. It is not the first time that Miliani has played with onomatopoeia and anagrams, having already done so in the performance oomh (2018).

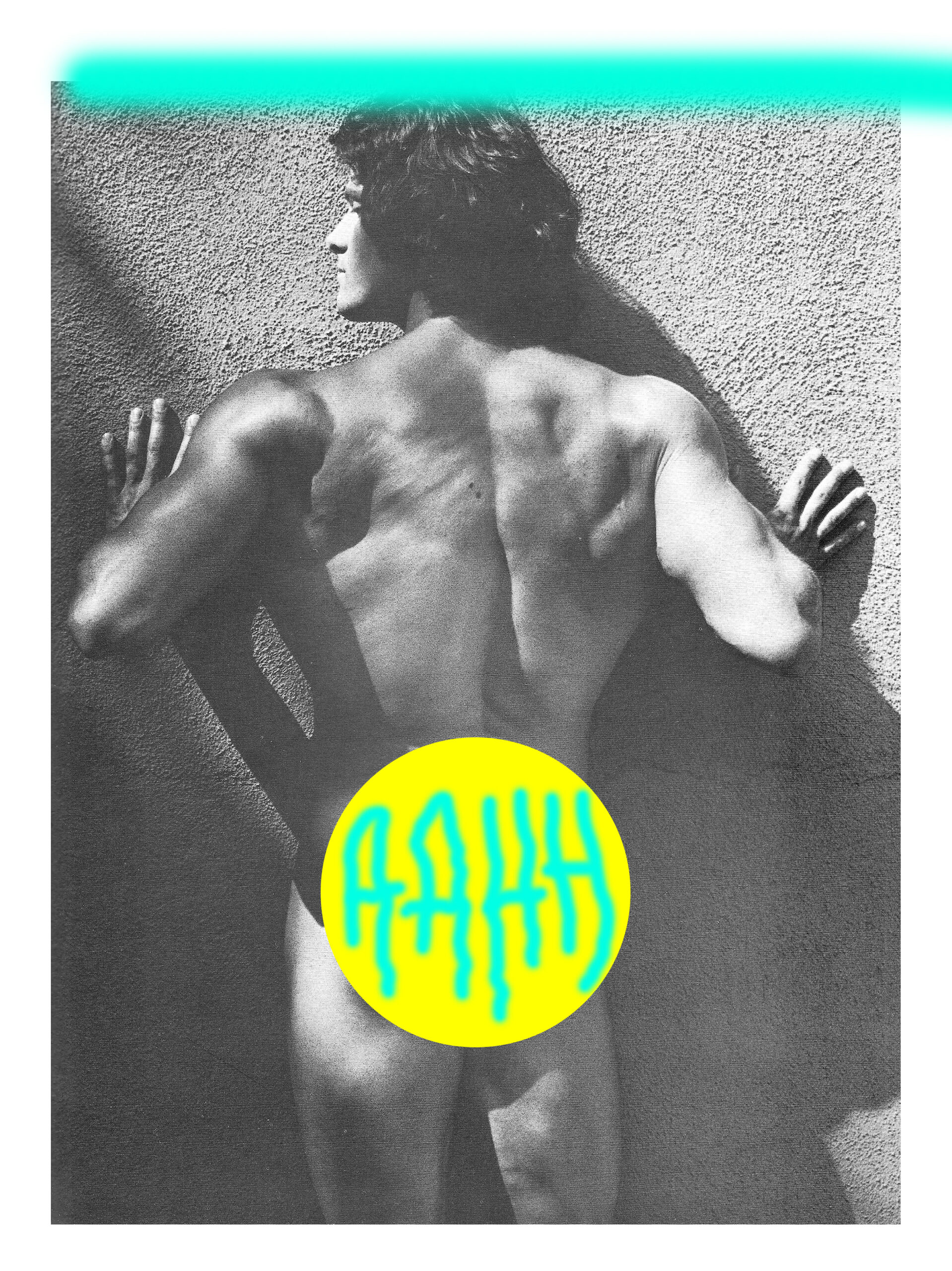

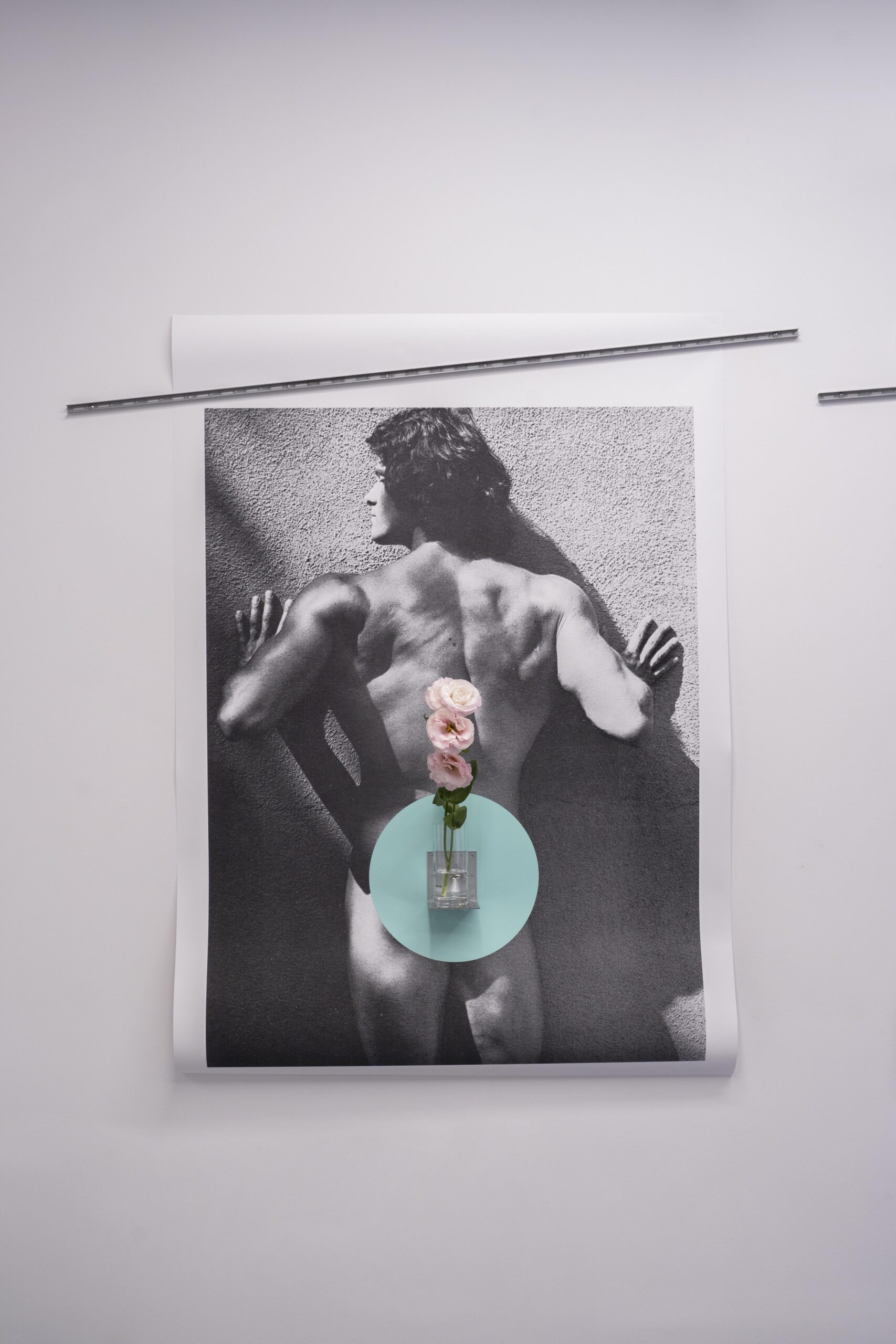

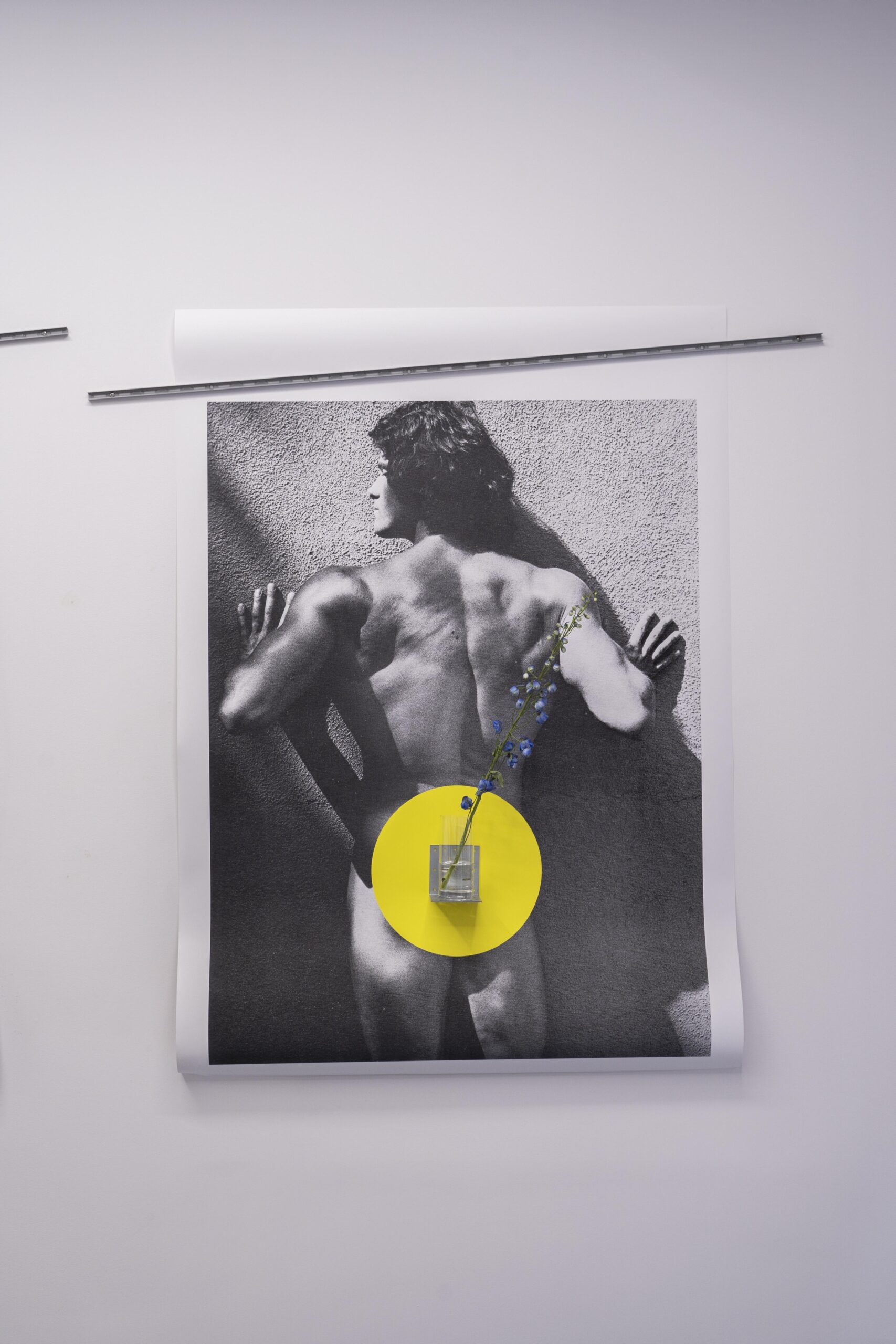

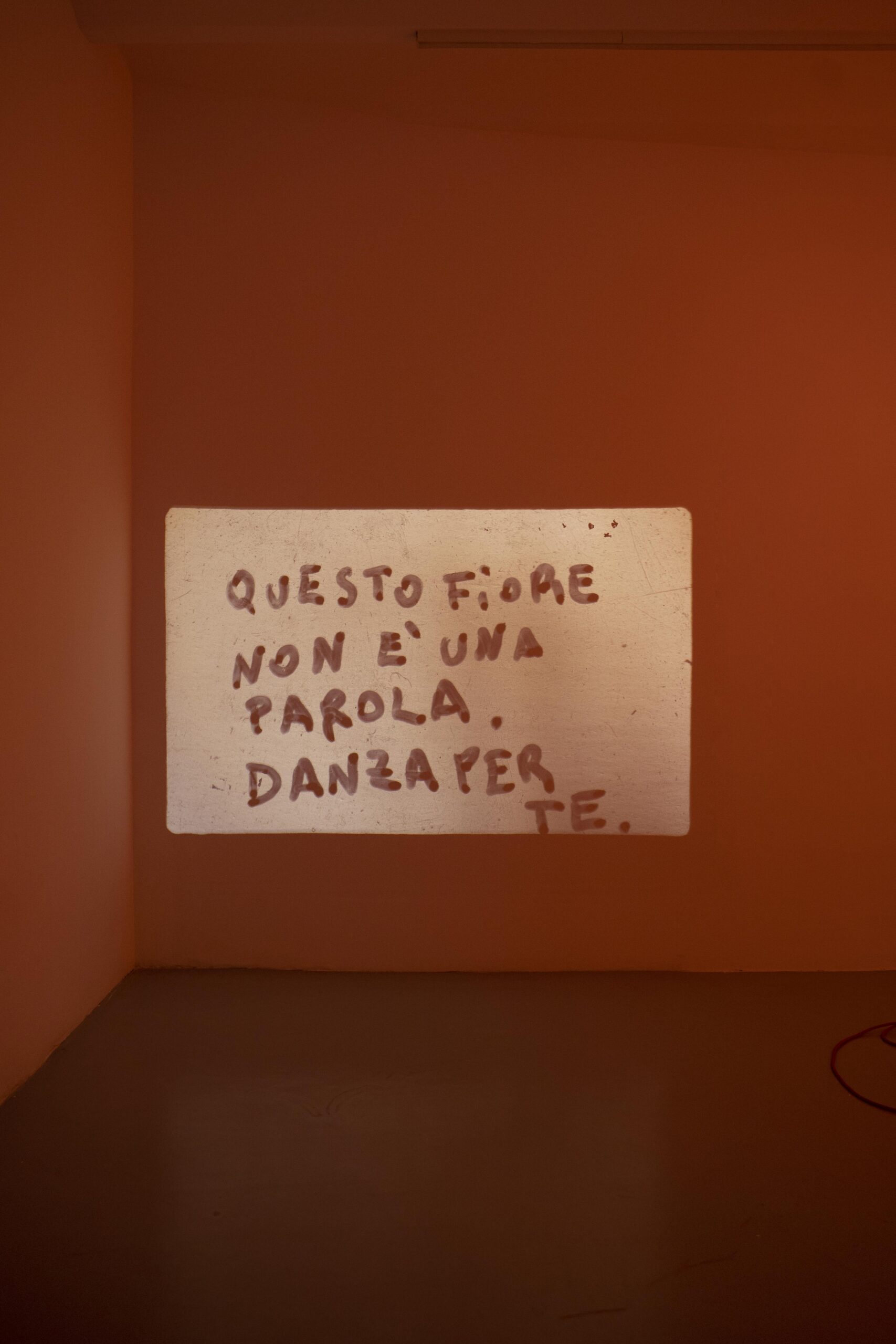

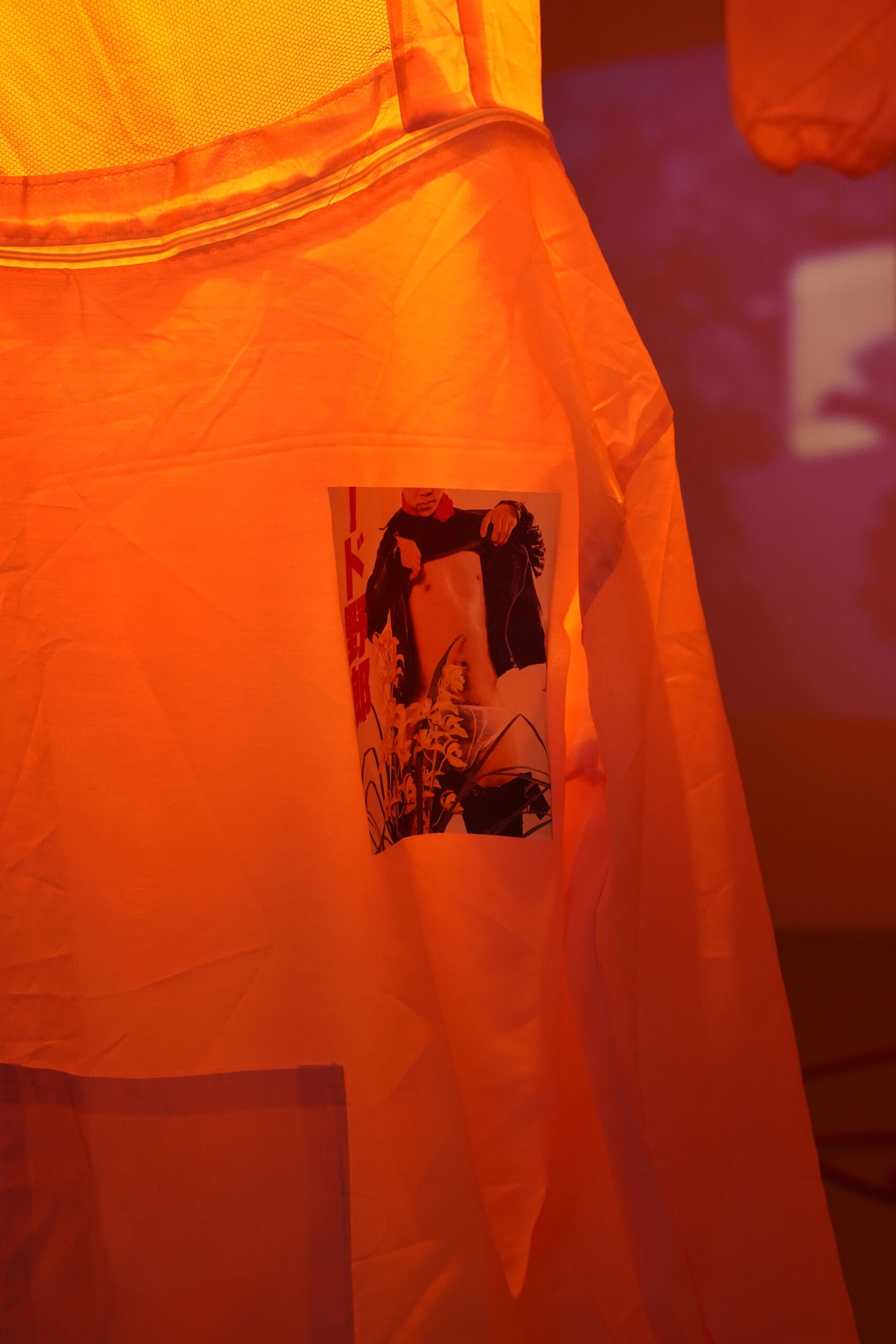

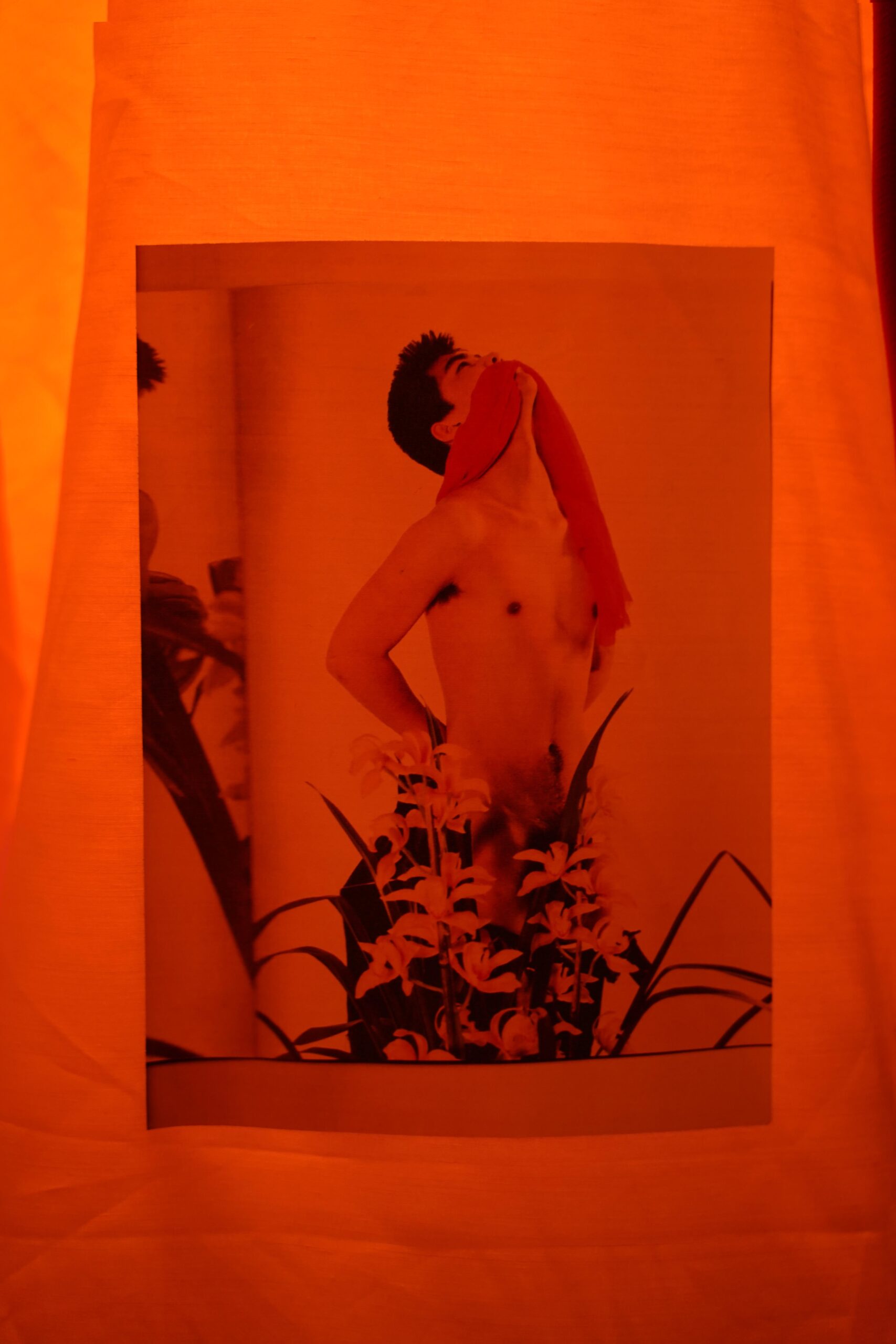

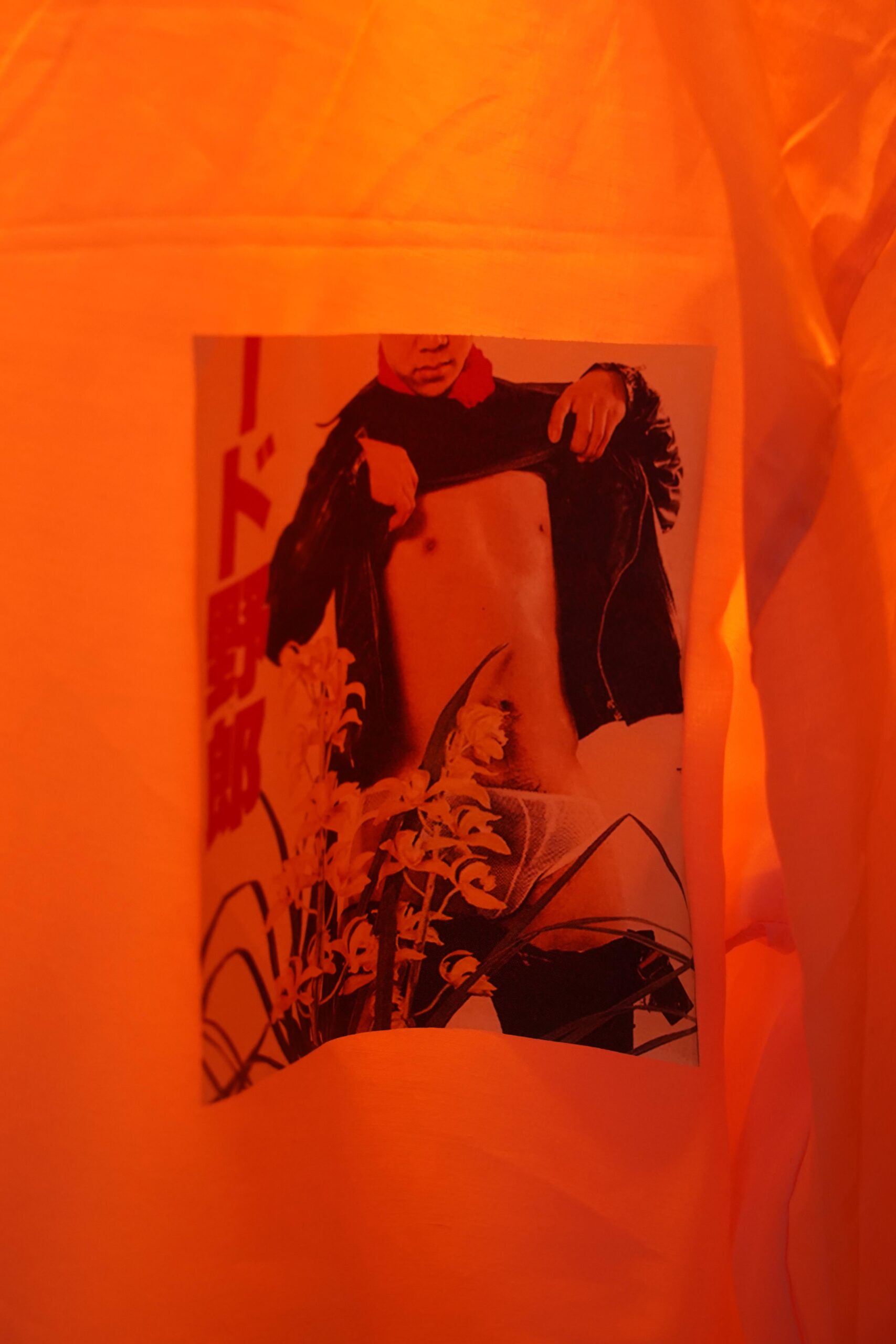

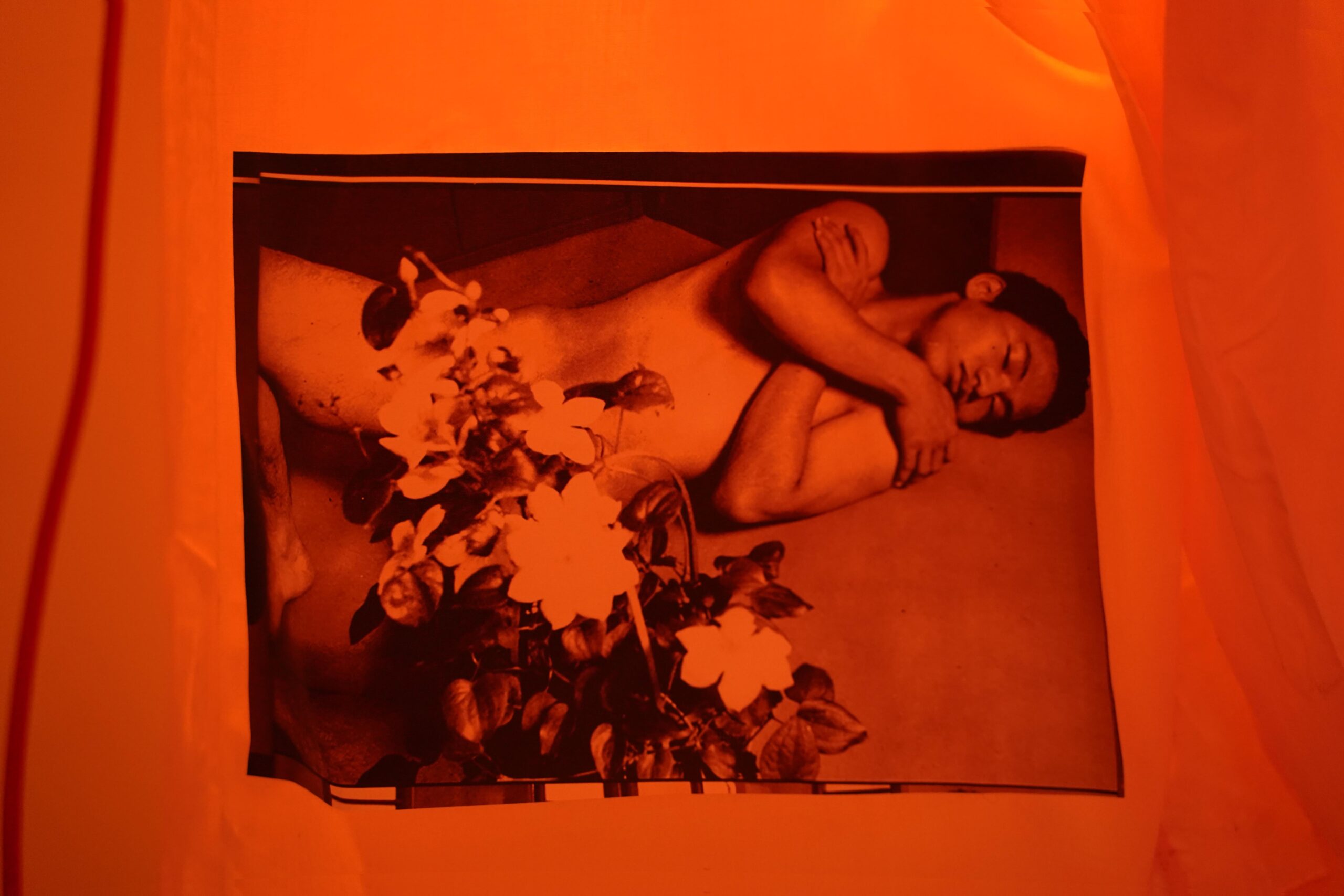

Finally, in the basement room we find three light sculptures whose inspiration is borrowed from a beekeeper’s suit. This protective clothing is in itself the maximum form of censorship, with a design that only makes it possible to intuit the bodies behind it. The three lamps are bodiless suits, divested of their use function, like a language without body. The wall at the back of the room is covered with images of flowers by means of a slide projection in the dark.

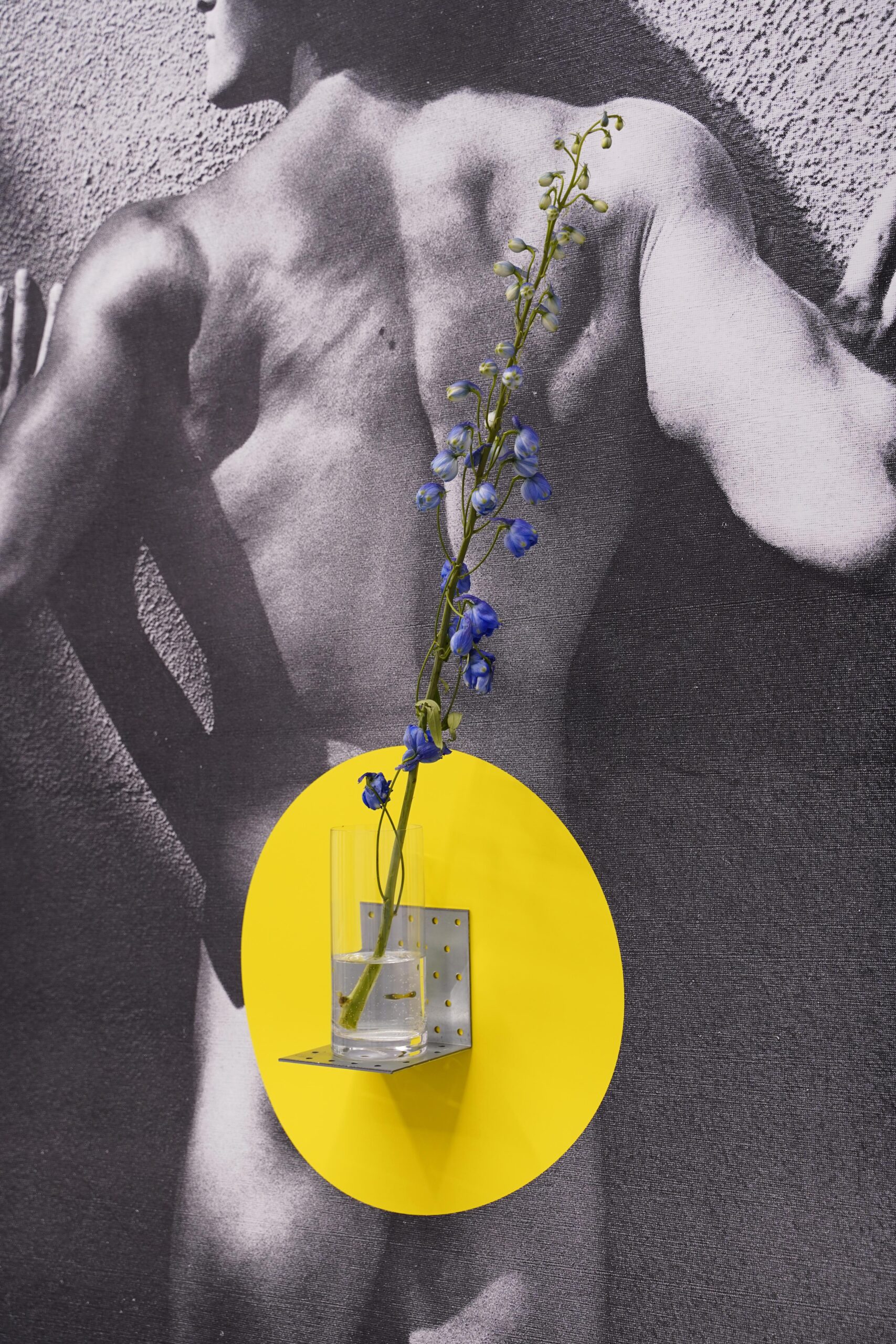

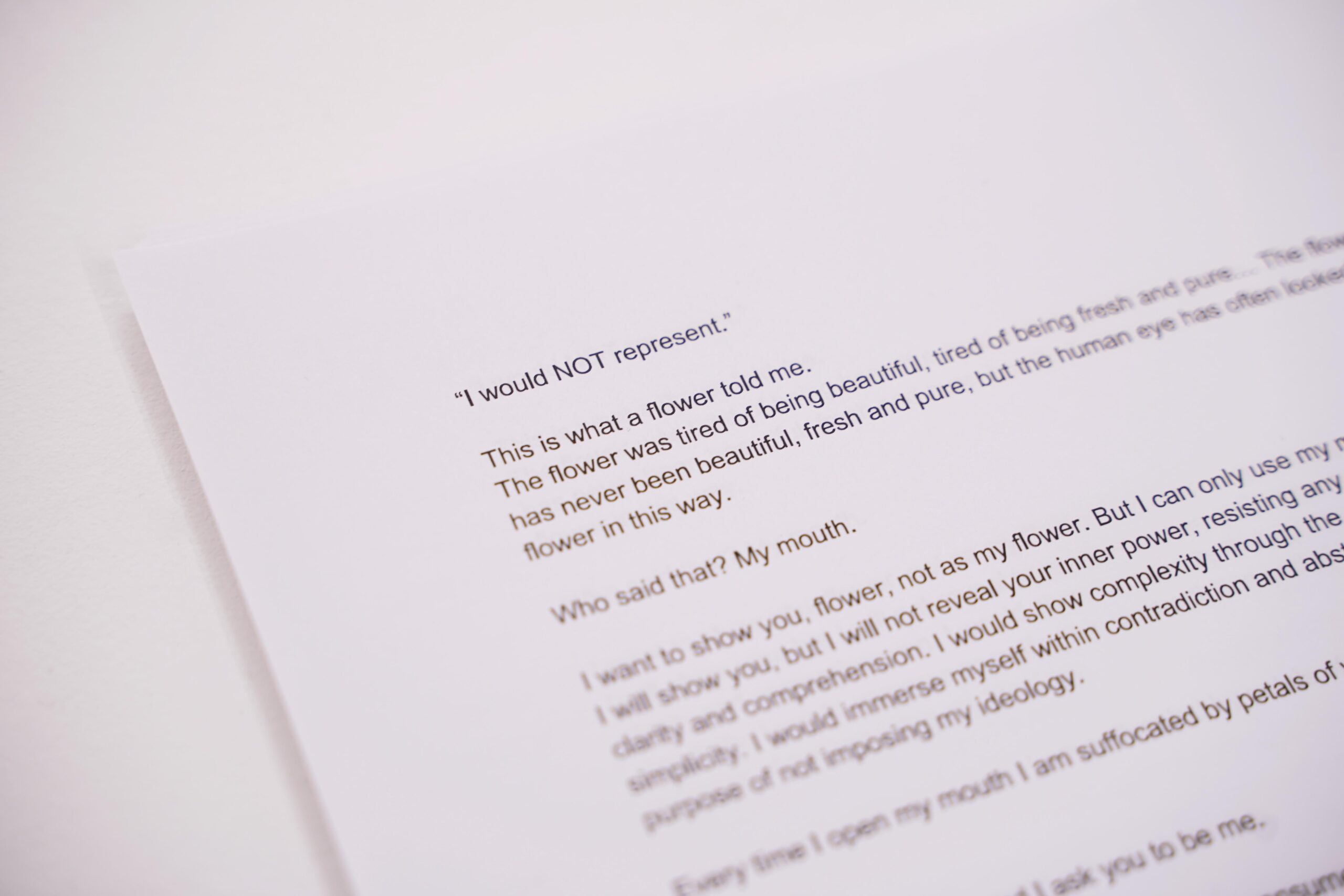

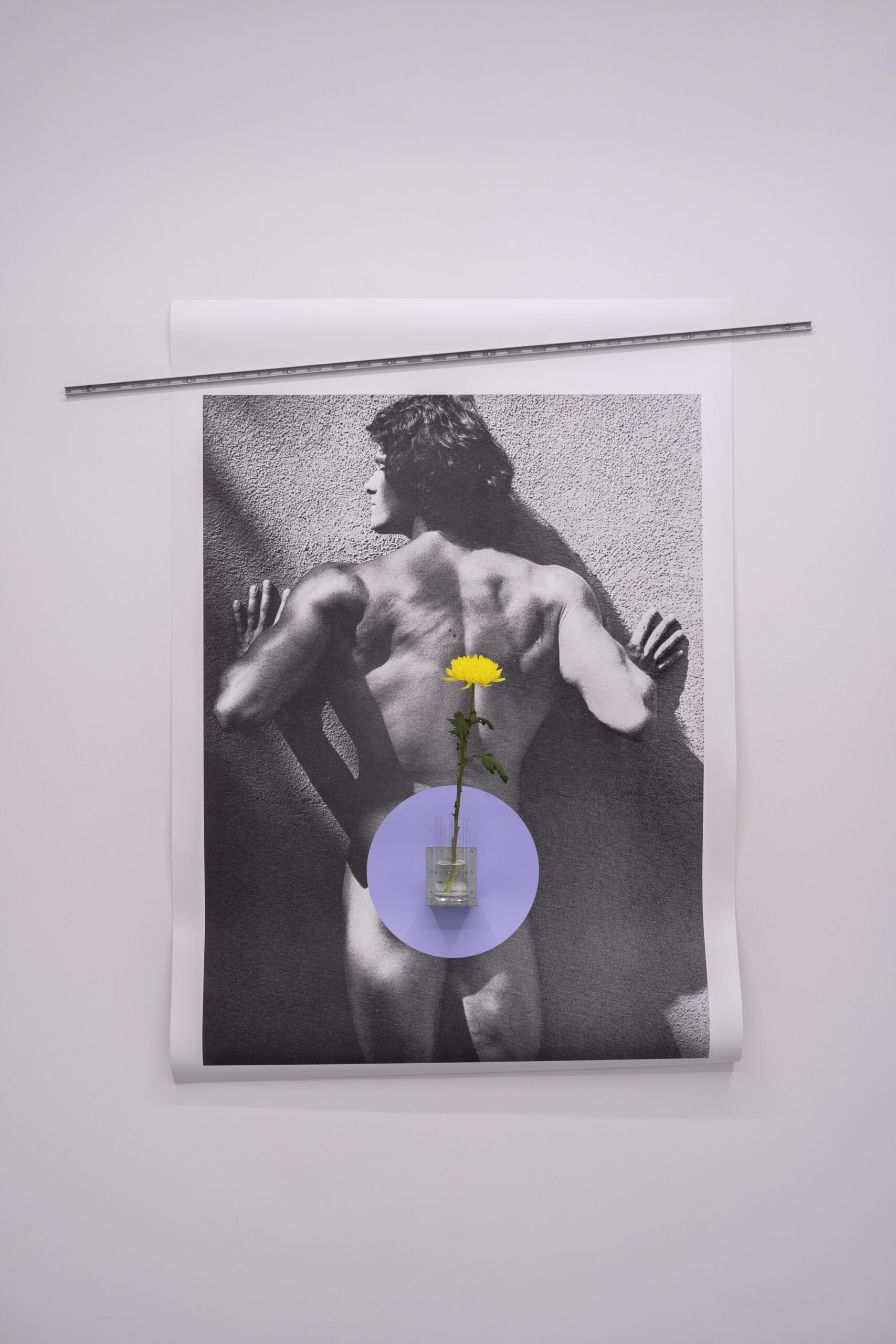

In Miliani’s personal text we can find the perfect coda to this narrative on his exhibition: The flower was tired of being beautiful, tired of being fresh and pure… the flower was never beautiful, fresh and pure, but the human eye has often looked at the flower this way.

This is Jackalope