What shone were your pupils. Your pupils dilated to their limits, disappearing in the darkness of your eyes. Your eyelids were like lilacs. And bags underneath that you would have liked to lift in order to halt the passing of time and stop the emaciation. But your body and those of the hundreds of others who were there were not going to stop. The only way was up, and you believed yourselves invincible in that fantasy. That’s how I imagine you in that concert in Madrid one hot muggy summer’s evening on 7 July 1982. Just before the rain fell. This story you return to me in broken fragments, you only remember until the moment the group came out on stage. When the singer appeared the heavens opened up. The storm broke. You always told me this story as if it were a historical landmark, which it was, one that is now part of the mythology of a generation that lived through that moment without knowing that their bodies were the barricade for the institutional violence of the time. Bodies that bear witness to a history that has not been told and which belongs to a memory that is burned and transformed into millions of dying embers that are lost in the darkness of that night and of many others you lived through together.

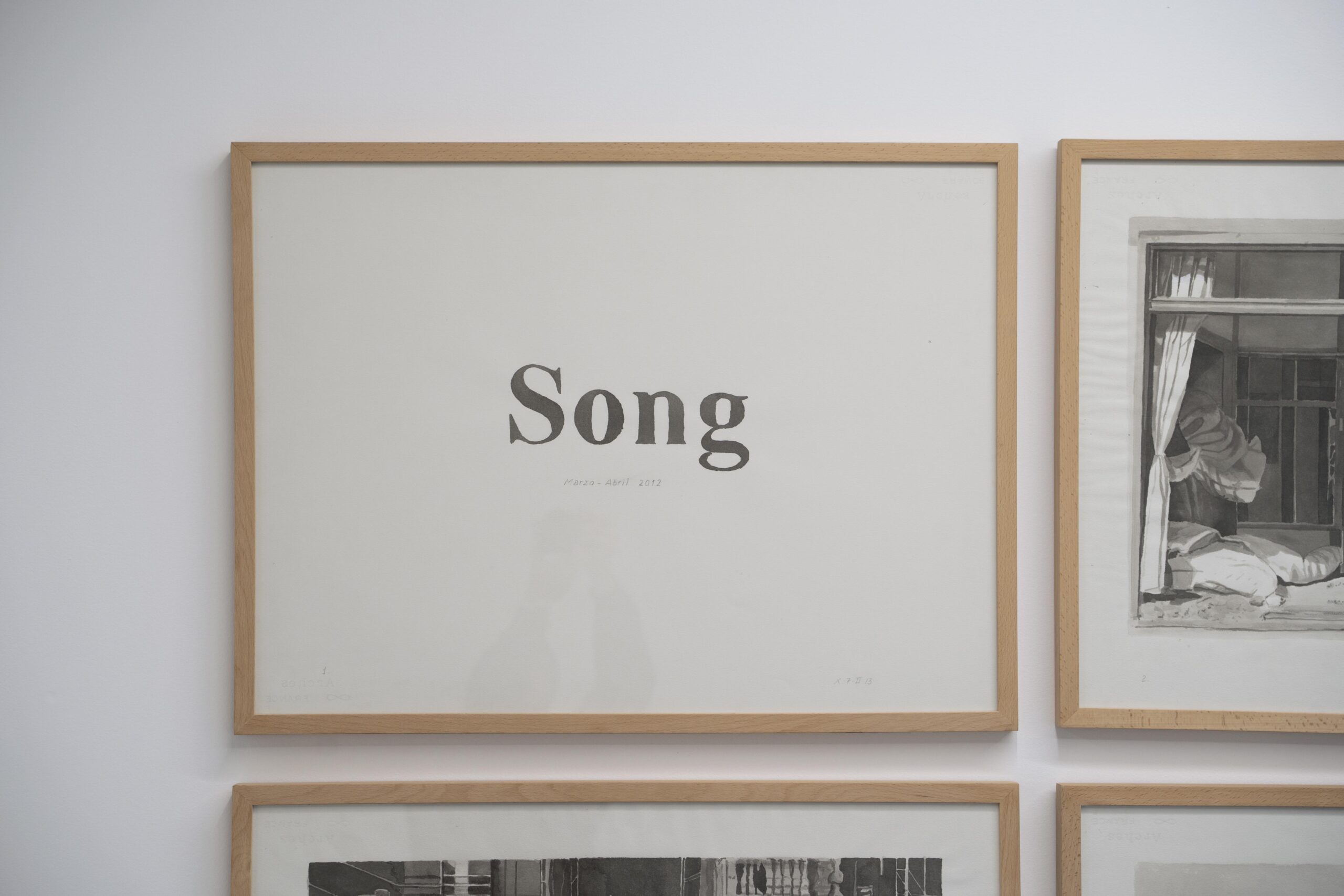

The tale I’m telling in bits and drabs comes from a family story I shared with each one of the five artists whose works occupy this space and now also belongs to them. This exhibition, called Fragments of past bodies that shine faintly and then vanish, is all about embodying the codes of what happens before the story is told, something which we can never materialize but which rubs up against and irritates historical narratives and opens the door for other accounts. It is a question of capturing gestures and stories that can only dwell in what has been embodied, because they take place through other codes of representation. This is the case of Song (2013) by Xisco Mensua, a visual chronicle which the artist builds like a twelve-part song through media archive images. And so an intrahistory of our most immediate political reality appears, told in twelve scenes.

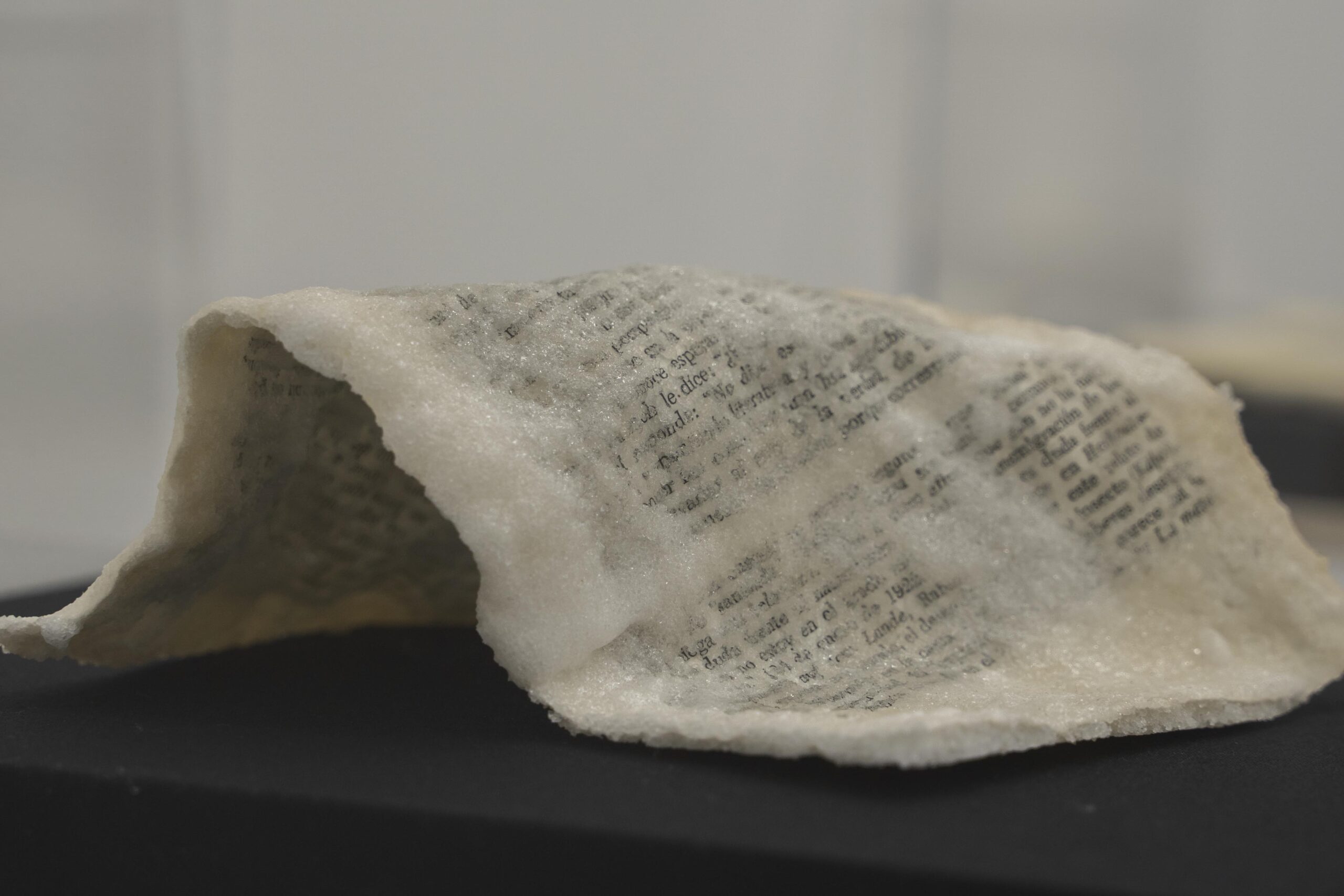

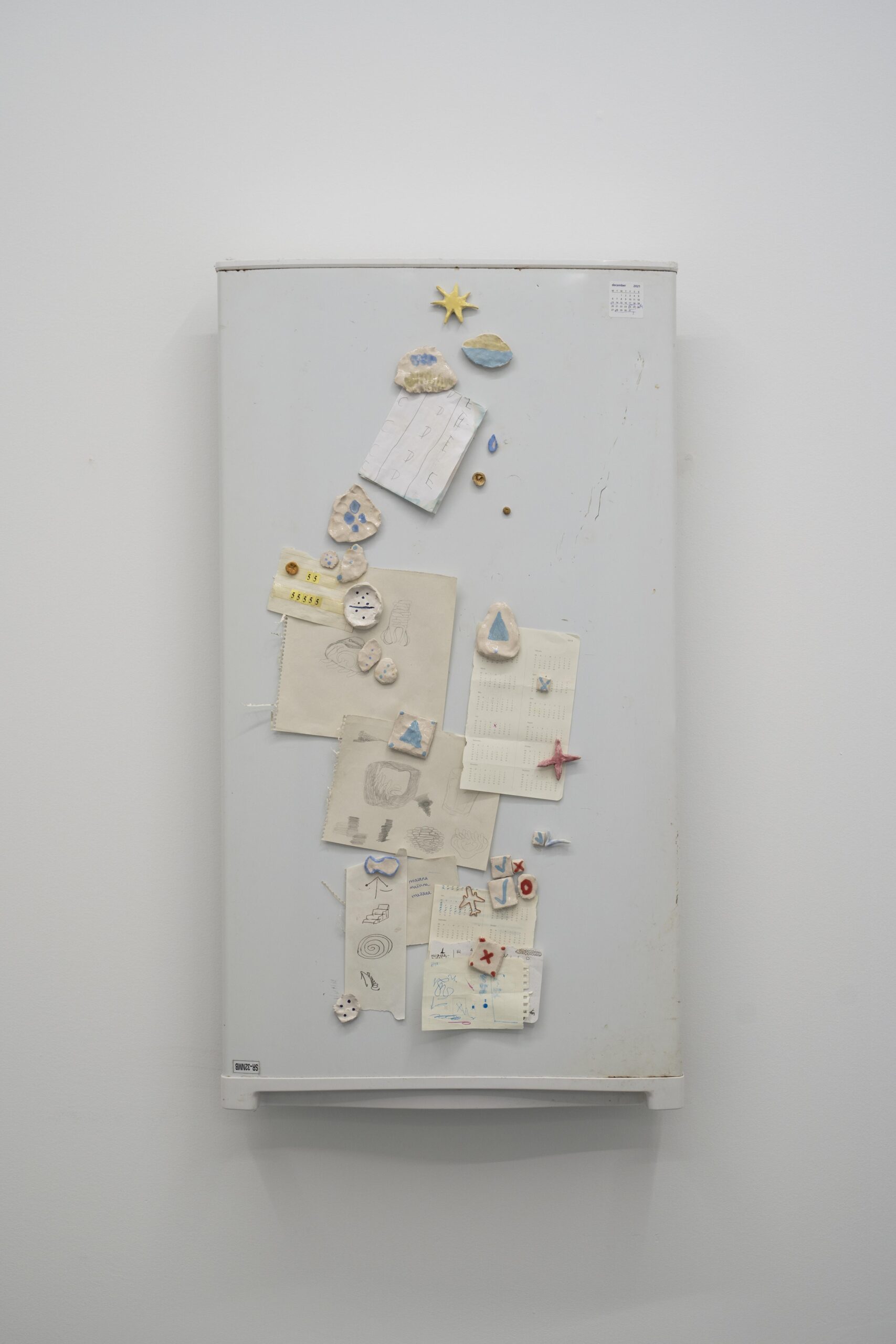

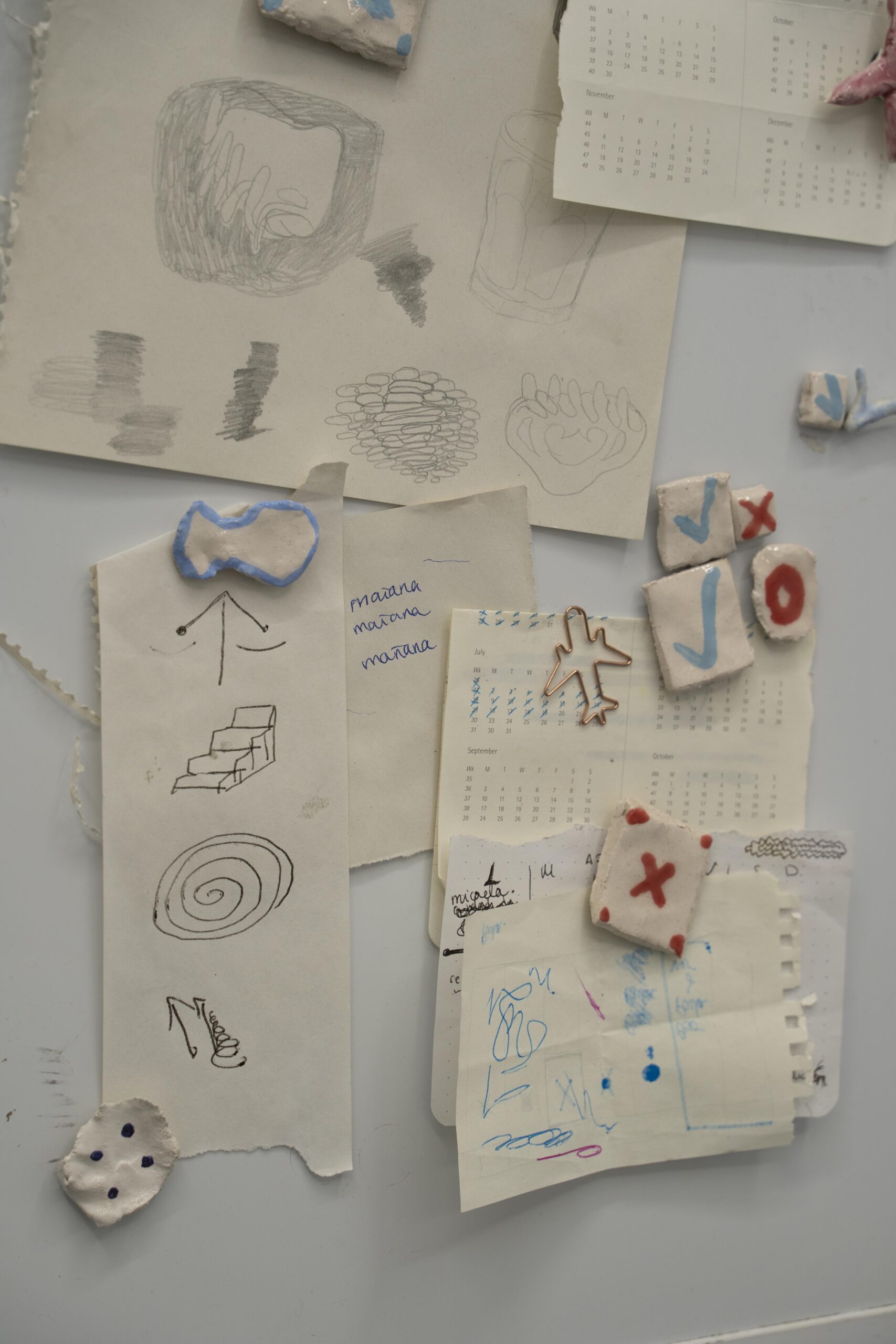

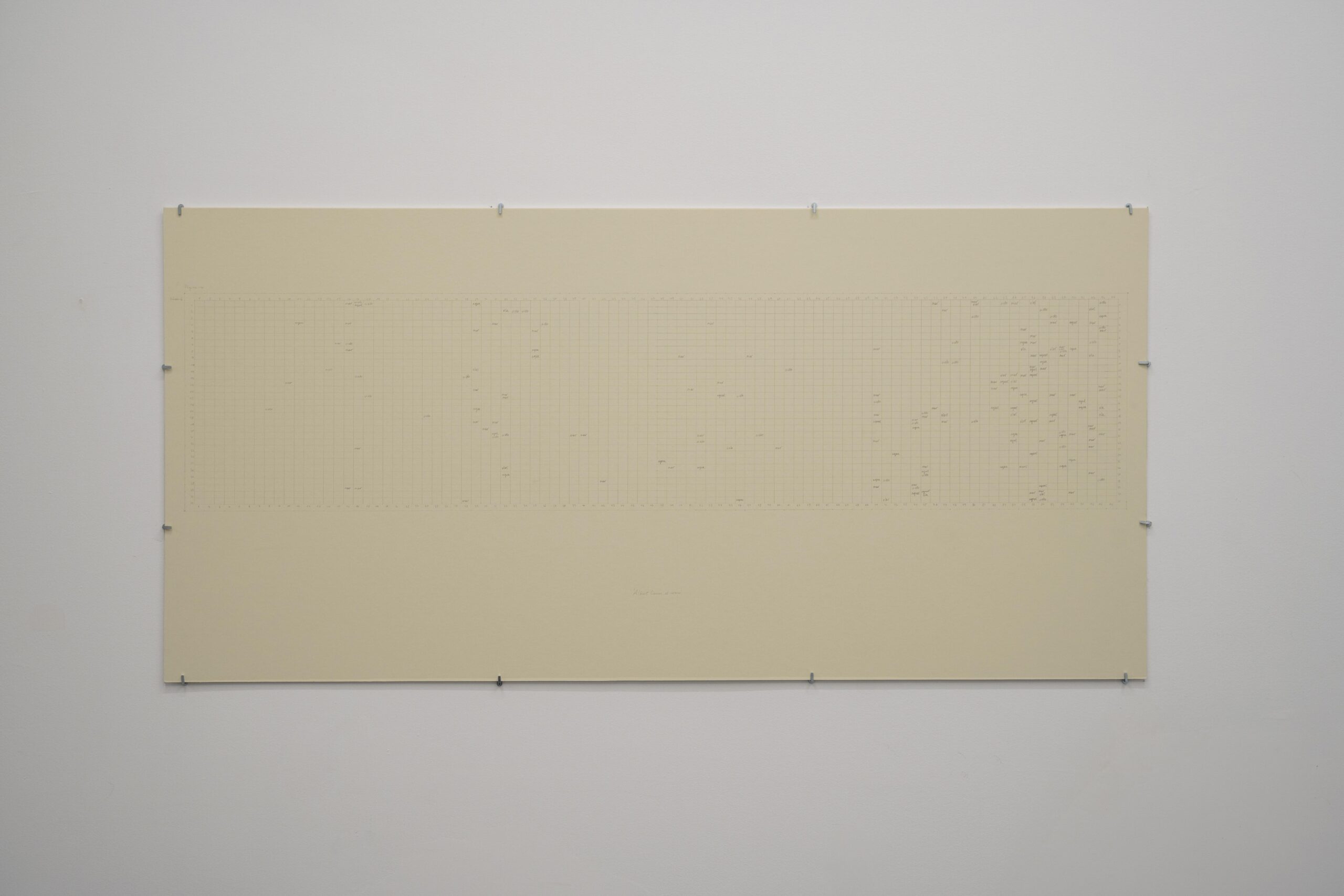

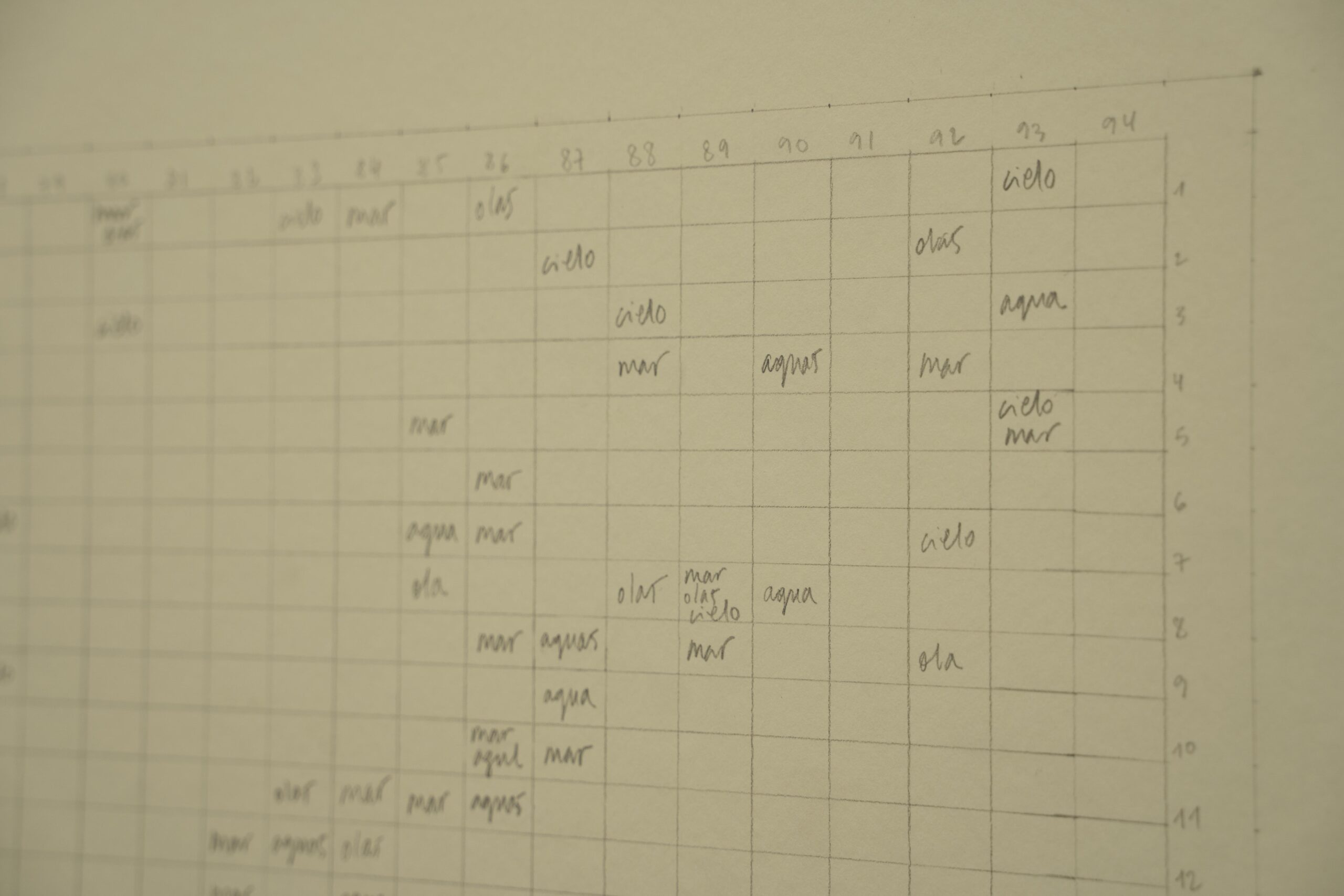

Greta Alfaro’s work engages with the lingering remains of absence from a shared memory which we tell ourselves, and which is fictionalized when we share it. The series Still Life With Books (2019), a group of sculptures made from pages of a book impregnated with sugar, speaks to us of the loss or impossibility of communication, and also the fraught relationship that exists on occasion between the text and the artwork, or between these and their authors and their audiences. At once, Puerta IV (Pasado mañana) (2021) by Marina González Guerreiro is a space for the narration of memories and desires for change that are built in the day-to-day as a place that eludes our everyday lives. The materialness of each one of the objects it contains constructs a new possibility for emotional transformation. Also on the engagement with the lingering remains of absence from a shared memory is Albert Camus, el verano (2022) by María Tinaut. A drawing made from rescued words: sky, blue, water, wave and sea, taken from one of Albert Camus’s texts. The result is the drawing of a horizon composed from fragments of the memories of the writer which are now trapped in a new presentness. The work Mira si he corregut terres (2020) by Mar Reykjavik which closes the exhibition is caught in the struggle to open up a space between analysis and action. A stage play divided into five acts exploring the intersections between tradition and novelty. The performance endeavours to grasp the anachronism implicit in novelty and thus to activate other possible narratives through the remnants of the past.

Each one of the works by the artists belongs to those past fragments that act like mediators of facts and events that are still to be told. They seek proximity, not objectivity, what will return them to the point of departure and the point of homecoming in order to ask themselves about what lies behind these intersections of historiography, what lies outside the text as a sad depiction of life.

Paula Noya de Blas