The legend of the Golem, the being created from clay by Rabbi Loew in the ghetto of Prague, has transcended its origins in Jewish folklore to become a metaphor for the fear of one’s own creations, which can escape all control and turn against those who conceived them. Rabbi Loew models and gives life to the Golem to protect his community by writing on its forehead the word “emet” (truth), which also means truthfulness and righteousness. When the creature loses control and threatens innocent beings, Loew erases the word from its forehead, or destroys it, according to the multiple versions of the popular tale. In other texts, the Golem is described simply as a servant, without mind or soul, that goes to work and is put away in a corner when it is no longer needed, like a household appliance or the helpful robots that populate American science fiction fantasies of the 1950s.

Undoubtedly, the golem embodies the desires and fears we project onto computers and all the technology stemming from the accelerated development of computer science in the last fifty years, especially artificial intelligence (AI), which is currently in the focus of public opinion. But before computers, the clay creature already represented the specter of the Other, that which is strange and incomprehensible, counterposed to the order of an authoritarian society that, whether as utopia or dystopia, is made up of perfect individuals, devoid of weaknesses and emotions. Underlying it all is the word that creates and dictates, be it the mystical letter combinations of the kaballah, legal systems or programming code. The creature and the loss of control over it are the key elements of the many stories that derive from the myth of the Golem, from Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley’s Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus (1818) to the numerous versions that already have a robot or an intelligent machine as the protagonist. But what usually remains in the background in these stories is the raw material that gives shape to the creature.

In Raw, Moisés Mañas rereads the oldest versions of the legend of the Golem to focus on this creation as something formless, raw, that acquires its own entity and function through a word that represents truth. The artist associates this amorphousness and the concept of truth with the data that machines collect from their environment, through sensors, or from our interaction with them, processing the vast amount of information that we provide with our actions on and off the net (if it is still possible to be “off the net”). This data, which we usually ignore and consider worthless, we give away to companies that offer us seemingly free services and devices without which we don’t know where to go. They are a surplus of our daily activity, something that sprouts naturally from every interaction with the screen and is deposited in some hidden place, where it settles.

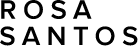

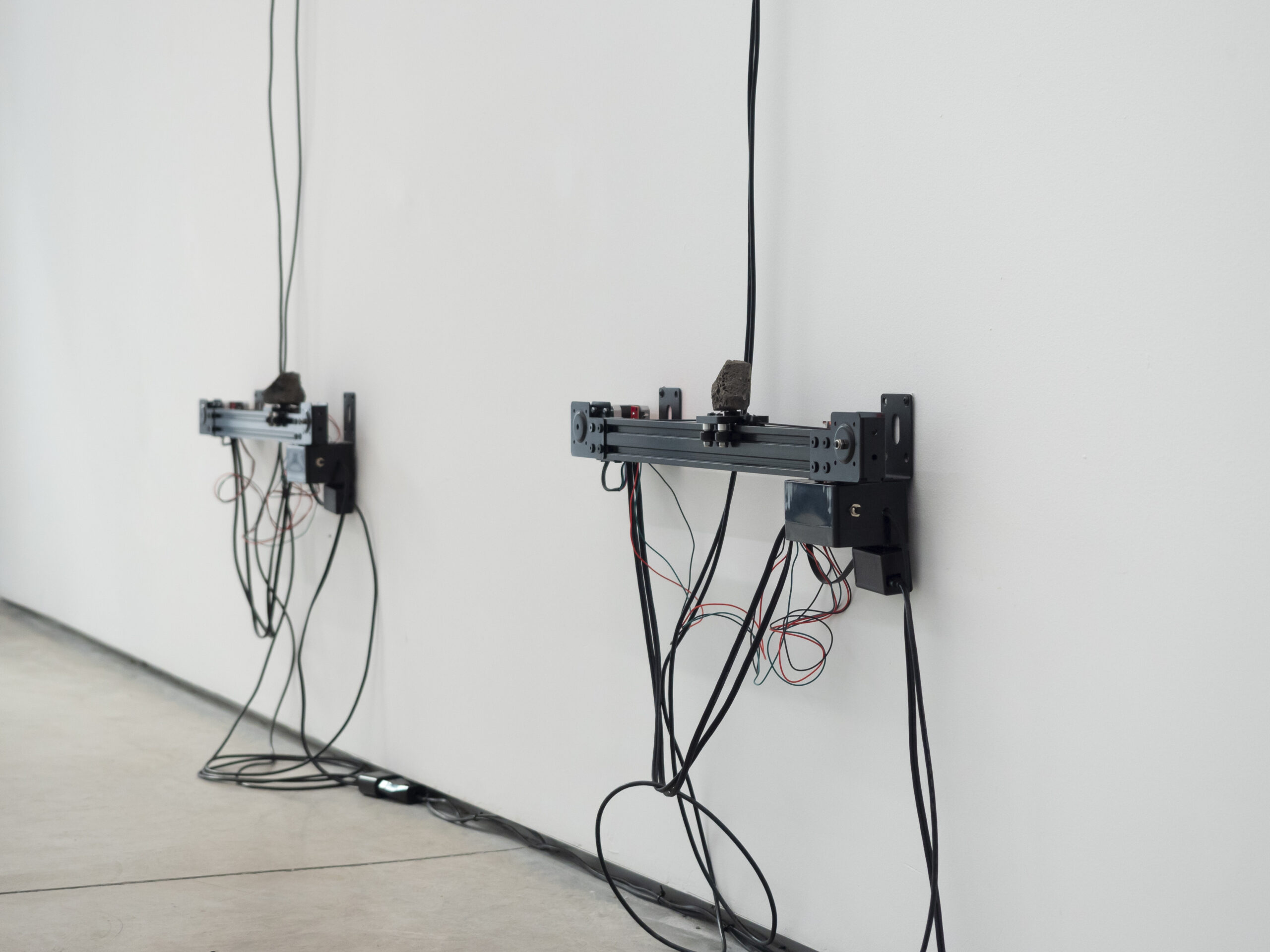

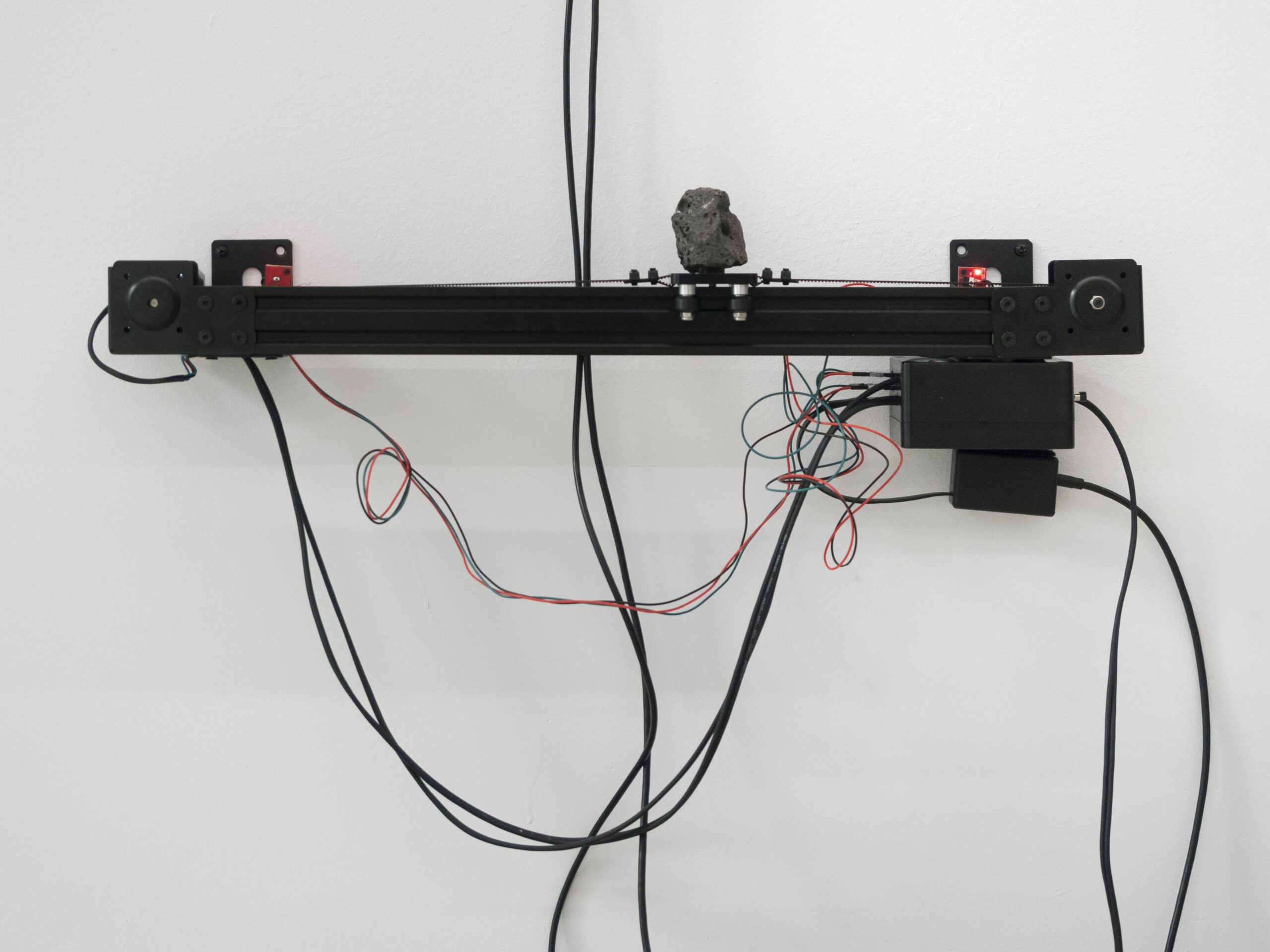

The first room of the exhibition hosts an installation that makes this process visible, by means of four screens connected to single-board processors and four rails on which pieces of slag obtained from the Roman mine of Cueva de Hierro (Cuenca) are placed. The computers detect nearby devices connected to the Bluetooth network and display the “raw” information obtained from them. At the same time, they activate the rails that move the slag pieces, thus reacting to the presence of smartphones and other devices carried by visitors.

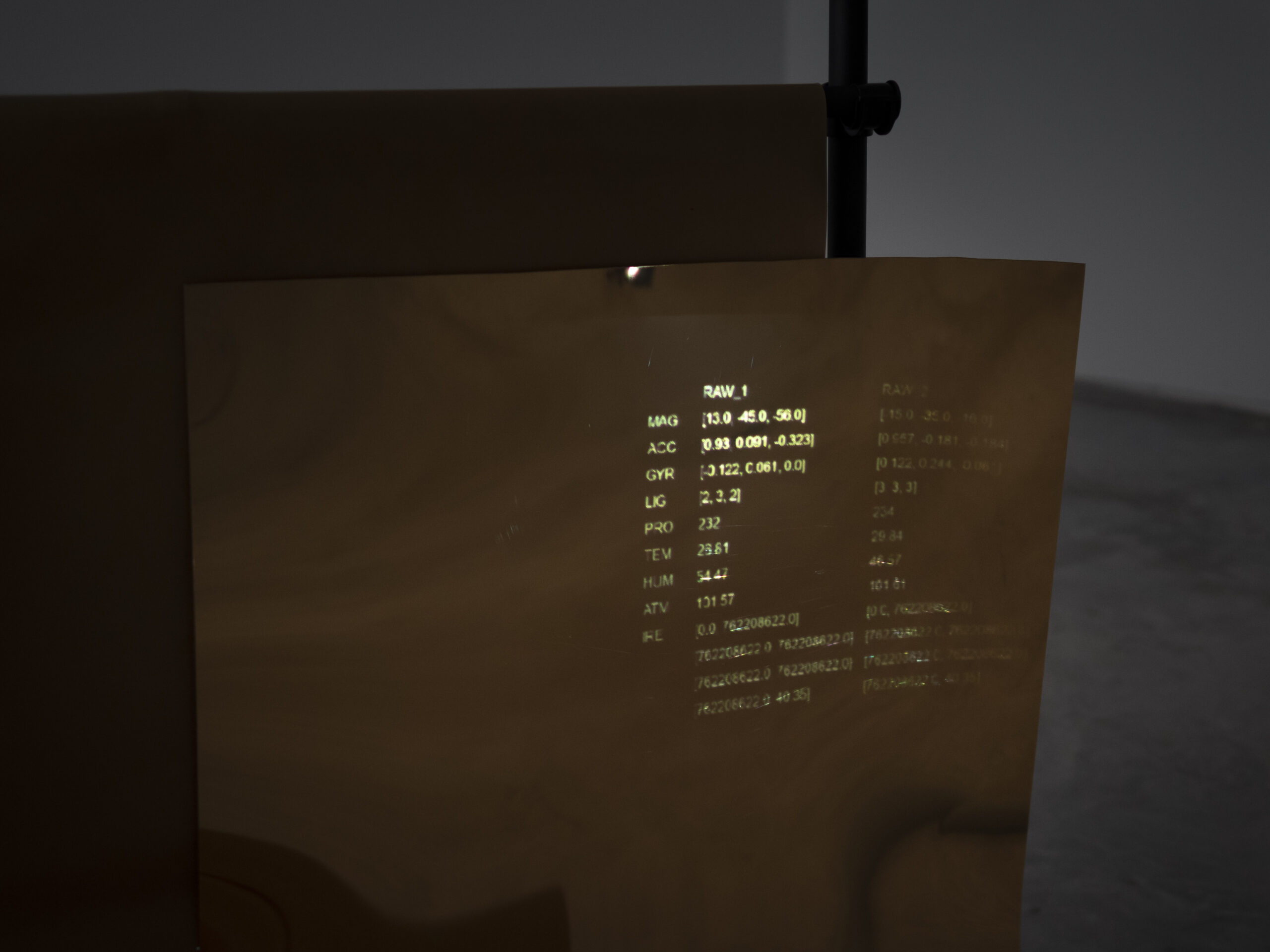

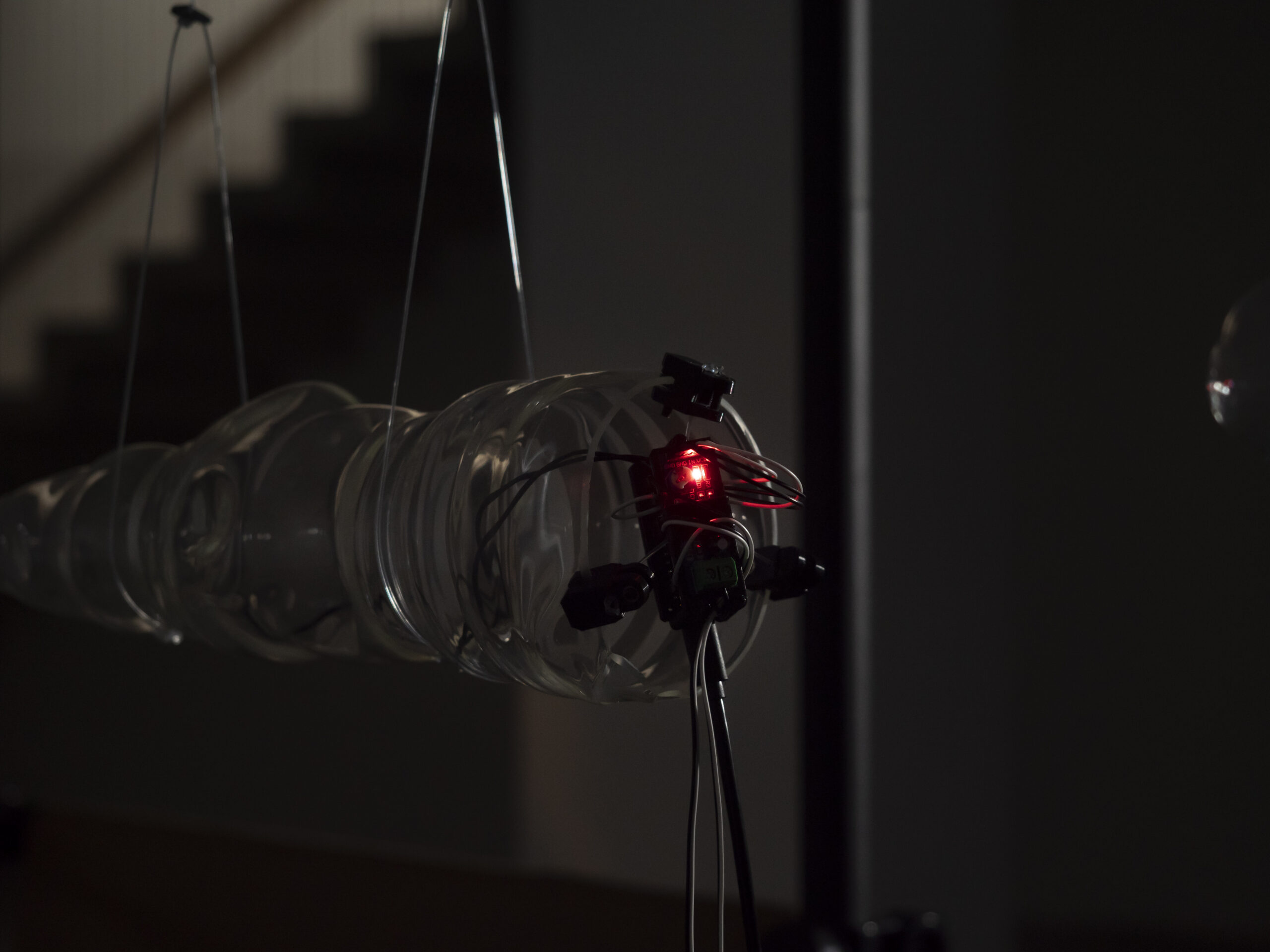

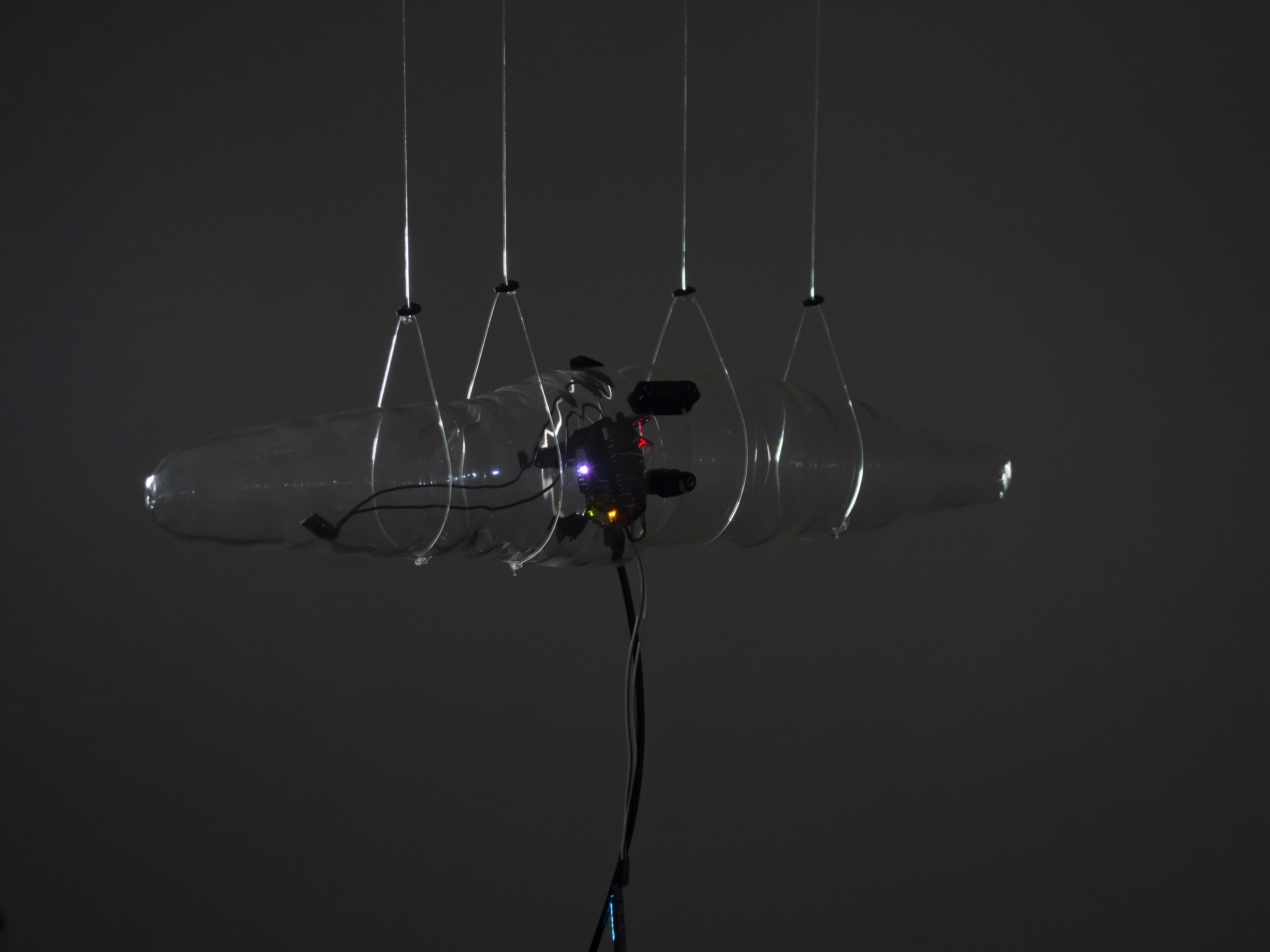

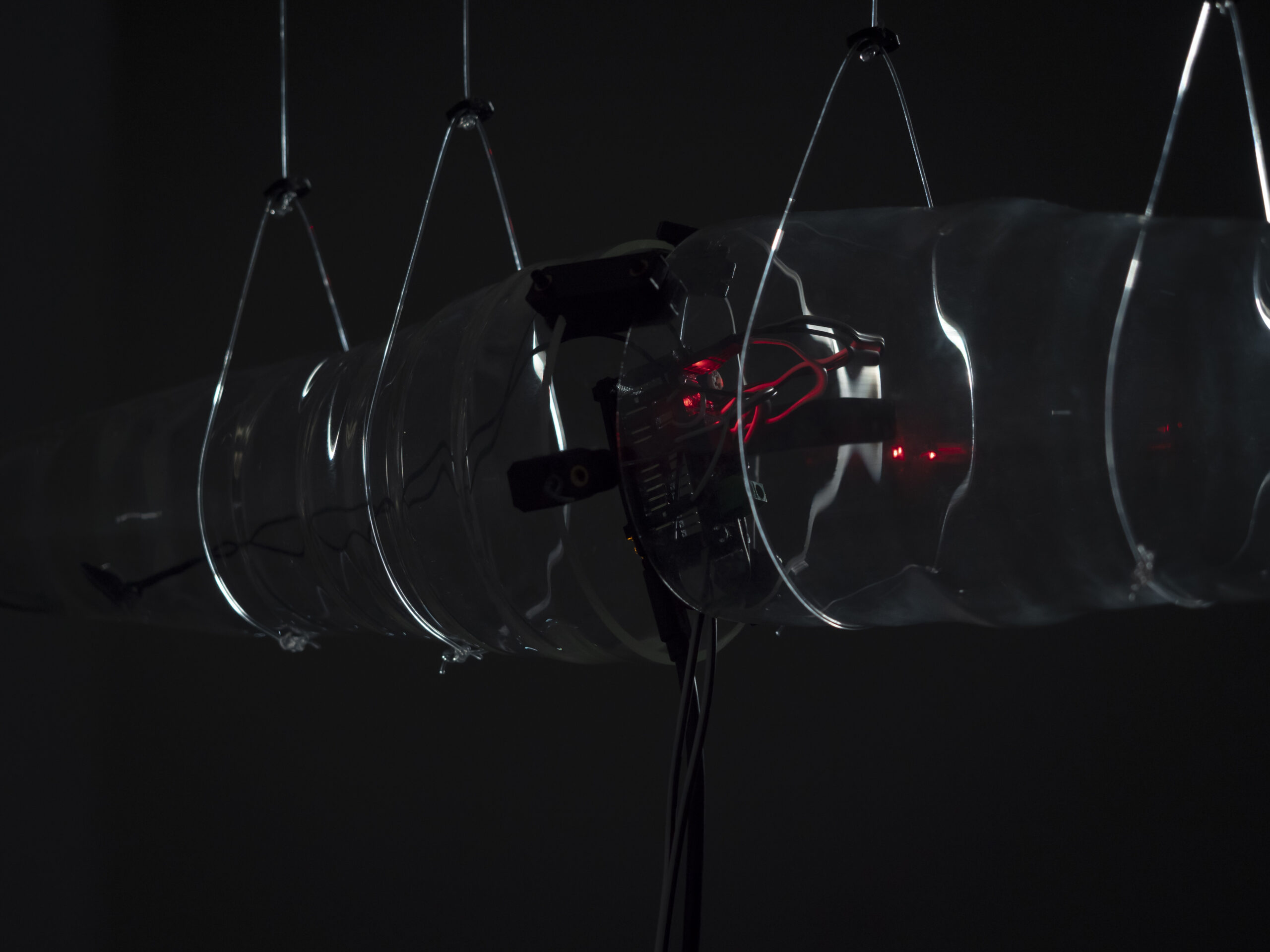

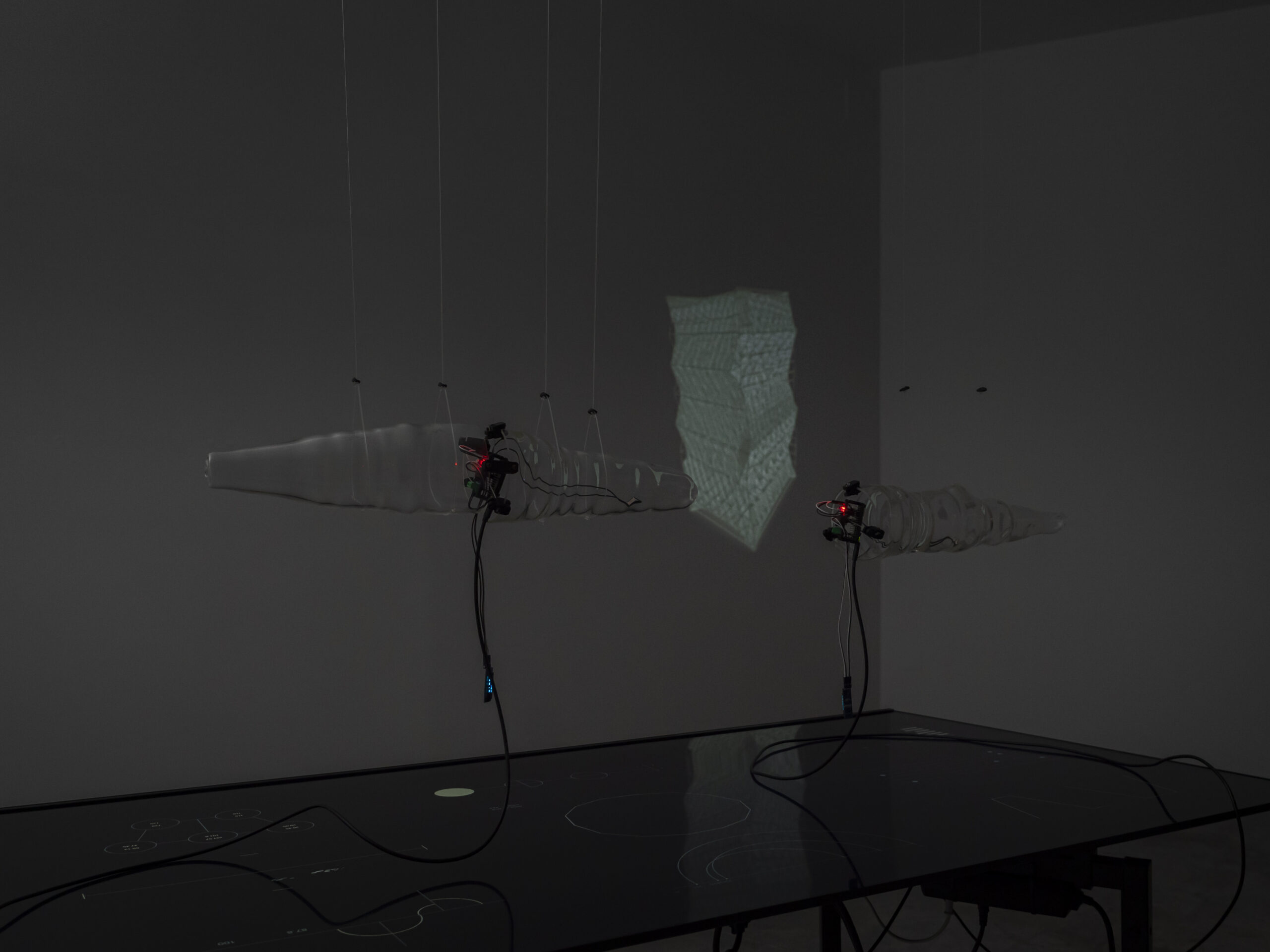

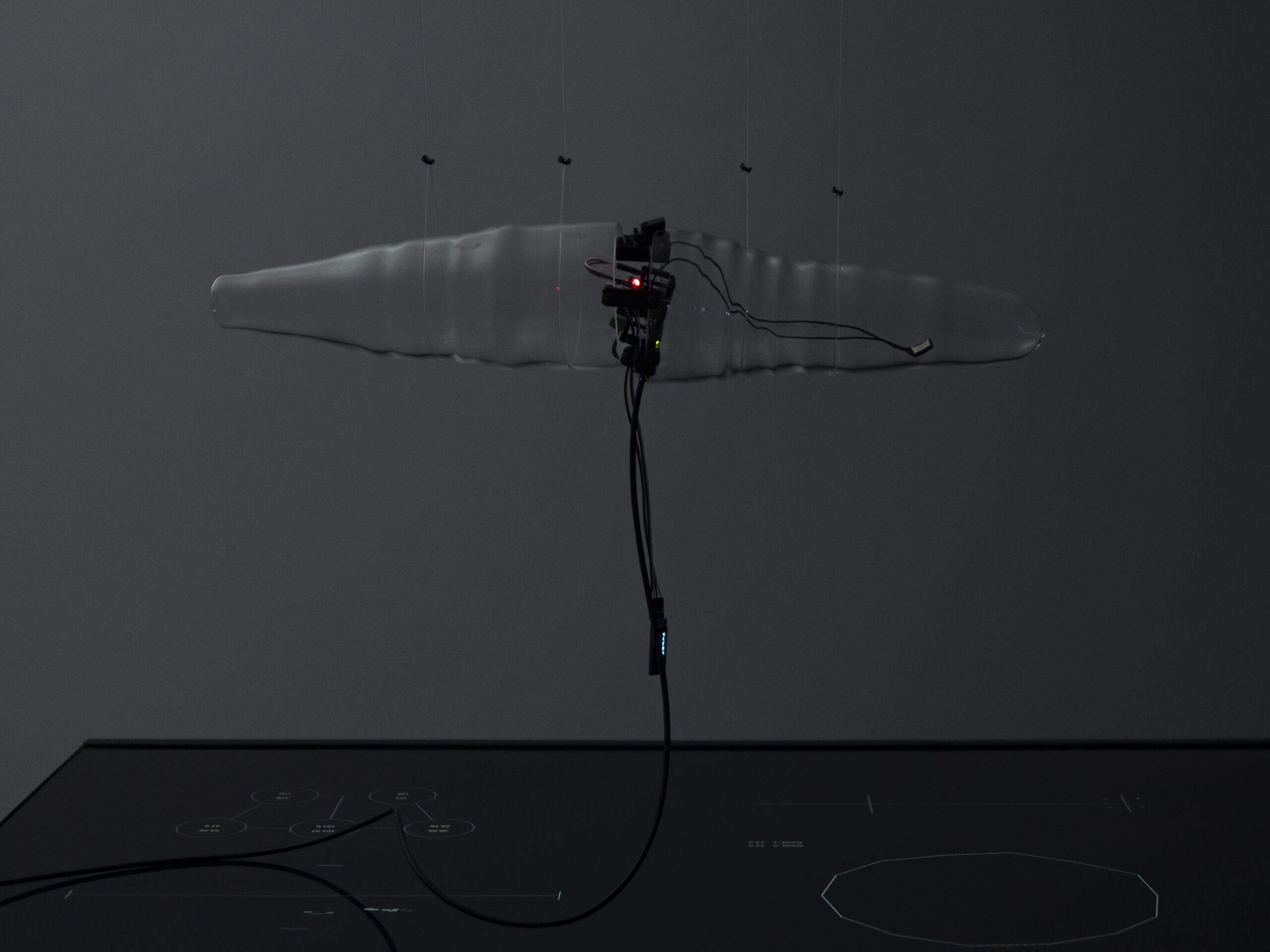

In the second room, two blown glass pods collect data from their environment (temperature, humidity, air pressure) and detect the proximity and movement of people. These data are displayed on a screen as enigmatic graphics devoid of any reference, while a sound signal marks the rhythm of the incessant activity of this machine and a projection shows images that complete the discourse of the exhibition and are key to deciphering its meaning: photographs of pieces of slag, excavated terrains and constructions generated with an artificial intelligence program follow one another alongside stills from the science fiction films Invasion of the Body Snatchers (Don Siegel, 1956), The Thing from Another World (Christian Nyby and Howard Hawks, 1951) and Alphaville (Jean-Luc Godard, 1965).

All these elements combine in a reflection on data as apparent waste that shapes the image of the world that artificial intelligence programs patiently elaborate, finding connections and similarities in latent space. Feeding on the information we provide them, they create digital doubles of each person, like those emotionless surrogates that emerged from the alien pods in Don Siegel’s film. The fear now being heard in the voices of AI experts already resembles that of the Arctic explorers who, in Nyby and Hawks’ film, extract a creature from the ice and watch with growing concern as it awakens from its slumber. The paranoia that in Cold War times materialized in fictitious beings from another planet has now been transferred to a series of computer programs, our own creations.

In Godard’s film, the Alpha60 computer subjects its citizens to an authoritarian regime, a dystopia that information technologies undoubtedly give rise to, and that in fact is already happening, but with the friendly face of an assistant. Again, let us not pay so much attention to the Golem and the control we can exercise over it, but to what it is composed of, the data we are feeding it. We are providing the raw material for a new algorithmic order, are we capable of rewriting the code that shapes it, or have we already become dross?

Pau Waelder

Credits:

Technical and installation assistance: Sergio Lecuona

Collaboration with glass sheaths: Sara Sorribes

https://vimeo.com/1065478874