Mira Bernabeu

Fri, May 27 - Fri, July 8, 2022

…de la crisis al riesgo… 2017 - 2022

This exhibition …from crisis to risk… comprises two projects made between 2017 and 2022: State of Uncertainty (2017-2019) and Micro-revolts (2017-2022). The evolution during these four years can be seen as a working through of various crises of different orders in highly diverse spheres. From personal and sentimental to collective and political; from breaking with […]

This exhibition …from crisis to risk… comprises two projects made between 2017 and 2022: State of Uncertainty (2017-2019) and Micro-revolts (2017-2022). The evolution during these four years can be seen as a working through of various crises of different orders in highly diverse spheres. From personal and sentimental to collective and political; from breaking with convention to overturn and chaos as the new world order. And with the global pandemic hovering above and overshadowing all other critical situations. Without any other motivation except art, without any other purpose than understanding the place we occupy in all this, Mira Bernabeu (Aspe, 1969) brings together both worlds and reaches conclusions which, to some extent, look to the future while turning to the past. Goya’s series of prints The Disasters of War and Los Caprichos subtend a contemporary narrative, yet contemporary only in terms of its currency and not in meaning and depth, as it continues to ask the same old questions as always.

Mirrors and Windows

On Mira Bernabeu’s State of Uncertainty

September 2019

A crisis is a phase within a wider cycle and is defined by shortages or scarcity, whose consequences occasion negative results. A financial crisis entails an economic contraction and a personal crisis usually induces an undermining of the emotional stability of the sufferer. Some of their features are similar, and plainly evince the dichotomy between macro- and micro-political analyses. The reconstruction following in their wake brings with it a series of remedies that, seen in hindsight, are like adding more layers on top of a surface, in ways like building a collage with photographic images and printed texts with which we give voice to what was conceived and written by others: the need to say with words already said what at times may seem unsayable. The images draw us closer to a reflection of oneself, just as the texts can console us for a loss—of whatever kind—through the empathy of being listened to.

The collages in this series called State of Uncertainty are, for Mira Bernabeu (Aspe, 1969), both a reflection in a mirror and an expansive view through a picture window. In them, the sediments of a personal crisis have settled on those of a much larger socio-political and economic one, channelled through personal experiences and covered by newspapers and other periodicals. The twenty-six works on paper conjure a vanishing world—the printed press—that refuses to accept its increasingly more insignificant and secondary role. Precisely because of this creeping sense of information’s loss of identity, because of its expansive, liquid appearance akin to a virus of misinformation more than a cure against it, the artist’s repurposing of physical printed media takes on the connotations of a gesture of survival: which is precisely what we are always urged to do to face, and overcome, a crisis.

The works have been built up with strata of information on a foundation of photographic paper with lines and grids like school copybooks. Layered on top of these pages, which bring to mind rote learning and the repetition of a gesture over time, are clipped images and texts culled from headlines and newspaper articles. In amongst this material which has grown organically, one can also discover handwritten texts (generally the titles of individual works, each corresponding to a particular type of crisis), as well as silkscreened words, dates or drawings which, once more, are buried, covered over or altered by the printed material. These actions operate like understated yet categorical strata that add a consciousness of time to the overall reading. On a surface of interconnected messages crowded or we could almost say incrusted against a glass, a translucent glaze has been applied that leaves the contents perfectly visible yet also has the effect of deftly unifying all the pieces. Again, this effect recalls the surface of a window that allows you to see what is on the other side, while at once providing protection and a sense of distance.

This action is by no means just physical or formal. The real lies beating in the unconsciousness of certain acts, sometimes throbbing like a wounded animal. In fact, this atypical gesture of serigraphy, in which a non-covering ink is applied to the surface to be printed, reverberates like a symbol of recollection or memory. At times as fragile as paper, layers of dust attempt to cover over events that still hurt. However, the semi-transparency of this controlled action refuses to erase them. In this fraught relationship between what has taken place, what we wish to overcome, and what remains as indelible as permanent marking, each one must draw their own lines; each one must decide how much of what has happened should be erased.

On the surface unified by the ink, the word ‘crisis’ in uppercase has been printed twice, one in white slightly misaligned over another in a darker colour, along with the critical typology to which the individual collage refers. Concepts alluding to family, personal, interpersonal and paternal-filial relationships as well as art, faith, technology, migration and so on can be read next to the core word, like tentacles of a larger organism or like subsections of a general theme, so broad it is almost unmanageable. At the same time, a date (09-02-2019) appears on the bottom of each work like a full stop. However, the rupture does not end there, but becomes even more radical. Each one of the collages has been cut across the middle into two halves, which are then coupled with another half. Ten of the twenty-six collages are smaller in size, thus further enhancing the sense of asymmetry between the works once recomposed. The chaos suggested on first glance at each one of the works gradually dissipates once you begin to understand the play of division and subsequent re-association. The concepts rooted in and derived from the crisis randomly join the beginning and end of words, creating neologisms that resonate with the overall idea of the main concept. Yet another gesture seemingly conveyed by the symbolism of confusion inevitably following a collapse, where everything tends toward the unexplainable. And, at once, this discloses the interchangeability of each one of the crises, undoubtedly interrelated and plainly impossible to isolate.

Since the mid-nineties, Mira Bernabeu’s artistic output has leveraged the body as a site for performative experimentation and visual representation, most notably though group photographs and videos recording their mise en scènes. The ostensible absence of the body here in this series of collages (though not foregoing faces, profusely on view in magazine clippings in which the gazes are negated) is made up for or complemented by a video self-portrait. In this piece, shrewdly screened on a smartphone, one sees the artist in a room-cum-studio as he finalizes the collages now on exhibit, spread out across tables and easels. As the video progresses we see how the artist, after finishing some pieces, empties the room of tables, chairs and armchairs, places the works on the floor, lies down naked on top of them with his back to us and starts to masturbate. The nakedness and the gestures of this action clearly hint at vulnerability and close the circle of a descent to the underworld and of physical and emotional regeneration. Whatever the reasons and the timing of the crisis, there will always be a point of departure: a necessary distance and, at once, a lingering reminder of our lowest point. Art allows us to transform ourselves into what we wish to become and also to escape from our deformed reflection. A mirror is a window is a mirror.

A Turn Forward

May 2022

The extraordinary events of recent years, with the pandemic surely chiefmost among them, have asked us questions unthinkable until then, placing us face-to-face with unforeseen situations and circumstances rife with uncertainty. A lot of the words used in this ‘pandemic time’ were prefixed with in- or un- as a negation of a normality which we wished and believed to be certain, even if we knew it to be fictitious. Fiction is not the opposite of reality but what makes it intelligible, which is probably why we fall back on it, coupled or not with science, to understand whether what we are going through is in fact an “inexact repetition of the future” or the ultimate truism that there is no more future than the present, the more reliable when the more predictable. And it is this apocalyptic social panorama; the revolt inspired by empty new concepts; the accountability of the mass media and their ideological filters; our bewilderment in the face of the unknown and life lived under uncertainty … that these “micro-revolts” bring under scrutiny.

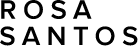

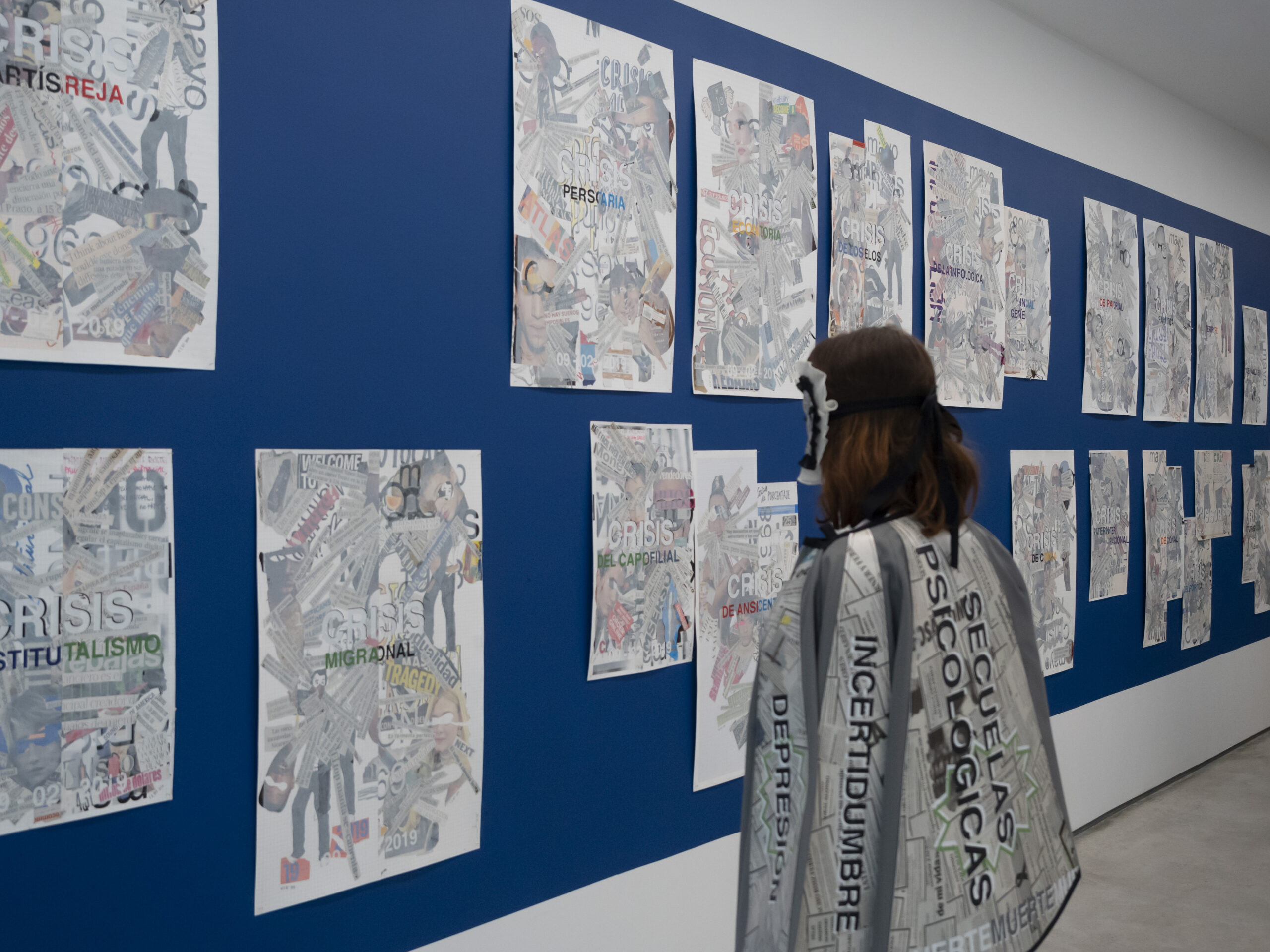

Art is a fiction of sorts but with greater expectations; a bounded pool of quiet water that aspires to be a raging torrent able to carve out a new course in history. When the overall set of circumstances which we call reality bursts violently out of its frame, we suddenly realize its capacity to completely change everything it touches. The very kind of transformation that art longs to instigate and which it instantly imitates, like a creature able to blend in with its environment. Just a few months before complete lockdown, Mira Bernabeu presented State of Uncertainty, a project rooted in a personal crisis which then branched off into all other possible crises. Almost three years later, conditions have altered his perspective. The collages then presented on tables, like maps of a lost direction, are now shown on the walls of the Rosa Santos gallery converted into colourful rejuvenated works. It is not so much an optimistic gaze as the certification of crossing through known ground. The transformation is also presented as a turn forward of the material used to record that time; giving body to pages of printed newspapers and magazines, shopping receipts or lottery tickets, tags, labels and other illustrated imagery. They have been stuck to objects and garments like banners, capes, masks, pointed capirote hats … which are used as props to film videos and take photographs, and now presented as moulted skin but also as a set of utensils always ready to be plied into action.

Microrrebeldías. Serie Mise en Scène XVII is a project comprising ten black and white photographs in unique edition prints; two videos also in black and white; the props made for the actions recorded in the photographs and videos; and a kiosk-like structure to display these elements in the gallery. The titles of the photographs are borrowed from some of Goya’s prints, though reinterpreting their meaning and updating their traumas. For instance, the first image, Bitter Presence, shows the stage in Teatre Romea —the scene of the actions— completely empty except for two benches, one on either side of the stage, which were used as bleachers for the cast of actors. This image is coupled with the tenth in the series (Of what illness will he die?), which also shows an empty space, with a darker central section, this time without benches. The other eight images mostly show the artist’s signature group scenes, with a special mention for Those Specks of Dust and its evident resonance with Goya. Mira interprets Goya’s work freely, unshackled from any specific gesture or stance, but with the same undercurrent of the acceptance of guilt. Capirotes are those pointy caps used during the Middle Ages to mark the wearer as guilty of a crime, misdeed or simply for professing a faith other than Catholicism during the sinister period of the Spanish Inquisition. Initially, a veil was attached to the conical shape to cover the bearer’s face and maintain his or her anonymity; the long surface was used to illustrate the crimes the person was accused of, almost like a comic strip.

During the opening, Mira Bernabeu and Chloé Thibault wear capirotes covered with articles from newspapers and various other printed material, as well as cloaks also partially lined with the same materials. They do not move, they make no gestures and do not interact with members of the audience. They are living-billboards; objectualized beings. The updating of this use of the capirote may suggest that these ‘offenders’ are carrying on their heads the conclusions of a crisis with profound collective roots, but whose burden is borne individually. They have accepted the role of representing all the conflicts derived from this pandemic, summed up in Abecedario pandémico. Diario de luto (Pandemic Alphabet. Diary of Mourning), one of the two videos on show, whose concepts are recited by actors and also depicted, screen-printed, in the layers, banners, pointed hats and sundry elements. The words in this alphabet (bookended by “Ansiedad” and “Zanjar”, akin perhaps to anxiety and zip) were chosen from clippings from different newspapers printed between 2020 and 2021, cut out, compiled and then screen-printed on other surfaces. The concepts operate like sections in an archive or library to file away news stories associated with different spheres of action, the real field of this project.

The sombre tone of the black and white photographs and videos reflects an updated simulation of Goya’s prints, but it also resonates with mourning. After a traumatic process, this phase recomposes the shattered pieces, trying to put them back together, to accept the loss and open up to a new phase which will always be challenging. And also exciting. The collage For Sale, an independent work that serves as a link between this series and the previous one, is a torrent of content made with texts from newspapers, photographs from fashion magazines, interspersed texts, some collaged and others screen-printed that take on the form of an alternative, radical advertising banner. The second video, The Pandemic Justifies Everything, alternates a reading of texts on social, political and personal changes brought about by the pandemic process, with the preparation for each one of the photographic compositions on the stage. Similar to videos of previous projects, Mira appears on stage carefully placing the cast in exact positions and carrying out very specific actions before photographing them.

The Kiosk structure, the heart of the exhibition, situated on the gallery’s lower floor, is both a display and support for the materials used throughout the process. Arranged on the wood and glass shelves, on the galvanized iron scaffolding, are bundles of newspapers and magazines (the raw material of the collages) alongside the objects made for the stagings (hats, masks, cloaks…), some collages and the videos from the theatrical actions, the latter shown on two screens. As such, it is a storage unit, a transitional place between the various phases of the process and an artistic structure, emulating the panels used in international art fairs and events. Likewise, the cabin-like shape (with pitched roof) also gives it an intimate, residential feel, although, that being said, it maintains a distance. The elements stored, and now exhibited, here including tote bags with pandemic concepts, remind us that time has passed; that we have learned from the process. We could talk about what has happened to us when we are able to see it with a certain hindsight; when the posture that will heal us, however much we keep turning our heads partially back, is to turn forward.

Álvaro de los Ángeles