Yesterday, I spoke with an oceanographer who told me that less than eight percent of the seafloor has been mapped. In addition to being unknown to humans, the seafloor is in a constant process of creating and destroying itself. Tectonic plates split at their boundaries and slowly move away from each other. Hot magma bubbles up and glides into the fractures and is cooled by seawater, becoming rock. The rock becomes a new part of the Earth’s crust. And then this process, called seafloor spreading, begins once more.

As he explained this to me, I thought about Maria Tinaut and the archipelago of scattered broken tiles she found in the field behind her house. Their blue flowers, once whole, now a sprawl of broken petals. She brought them to her studio and looked for where the winding, faint lines had originally joined and tried to bring the disparate parts back together. “To be a good human being,” philosopher Martha Nussbaum said, “is to have a kind of openness to the world, the ability to trust uncertain things beyond your own control that can lead you to be shattered.” But what happens in the wake of the kind of breaking that Nussbaum describes? Tinaut’s piece Untitled (Blue 1) – a few dozen pieces of almost-but-not-quite matching bits of tile closely embedded in gray joint compound – offers one answer: act like the ocean floor.

In Wish Me Luck for the New Year she printed a farewell letter in vinyl and installed it across three empty billboards in Valencia’s subway. These were located in consecutive stations, following the line from her neighborhood to downtown. The letter was sliced vertically and, in order to read the complete sentences, one needed to travel between the three stations. I never saw this work in its original habitat but, knowing me, I would’ve taken photos of each piece, puzzled them together at home trying to decode her note meant for someone else. But to what end? I would have finally arrived only to learn that she was already gone.

Wish me luck for th – e new year. I still remember – everything.

The writing, disjointed across time and space, is already looking towards separate futures. “What remains of a couple when it’s gone?” asks Hannah Black in her essay The Couple Form. “A small collection of souvenirs: phrases, images, sensations. These fragments persist long afterwards, as vivid as they are completely and radiantly meaningless, as if they were signs that will one day reveal their secrets.” But what if the spaces between the fragments are the signs? Or if the signs have nothing to reveal?

Around ninety-five percent of the ocean is in darkness. The oceanographer described his work of mapping the seafloor as a practice of speculating what-could-be in the large swaths between what-is-known. As the ocean gets deeper and darker, he has to use lower and lower sound frequencies to measure the canyons and seamounts. And the lower the frequencies, the more imprecise the measurements get. That sounds about right. The deeper we go into the unknown, the more we lose our bearings and our tools for assessment. But it is, as John Berger writes, “on the side of loss that hope is born.”

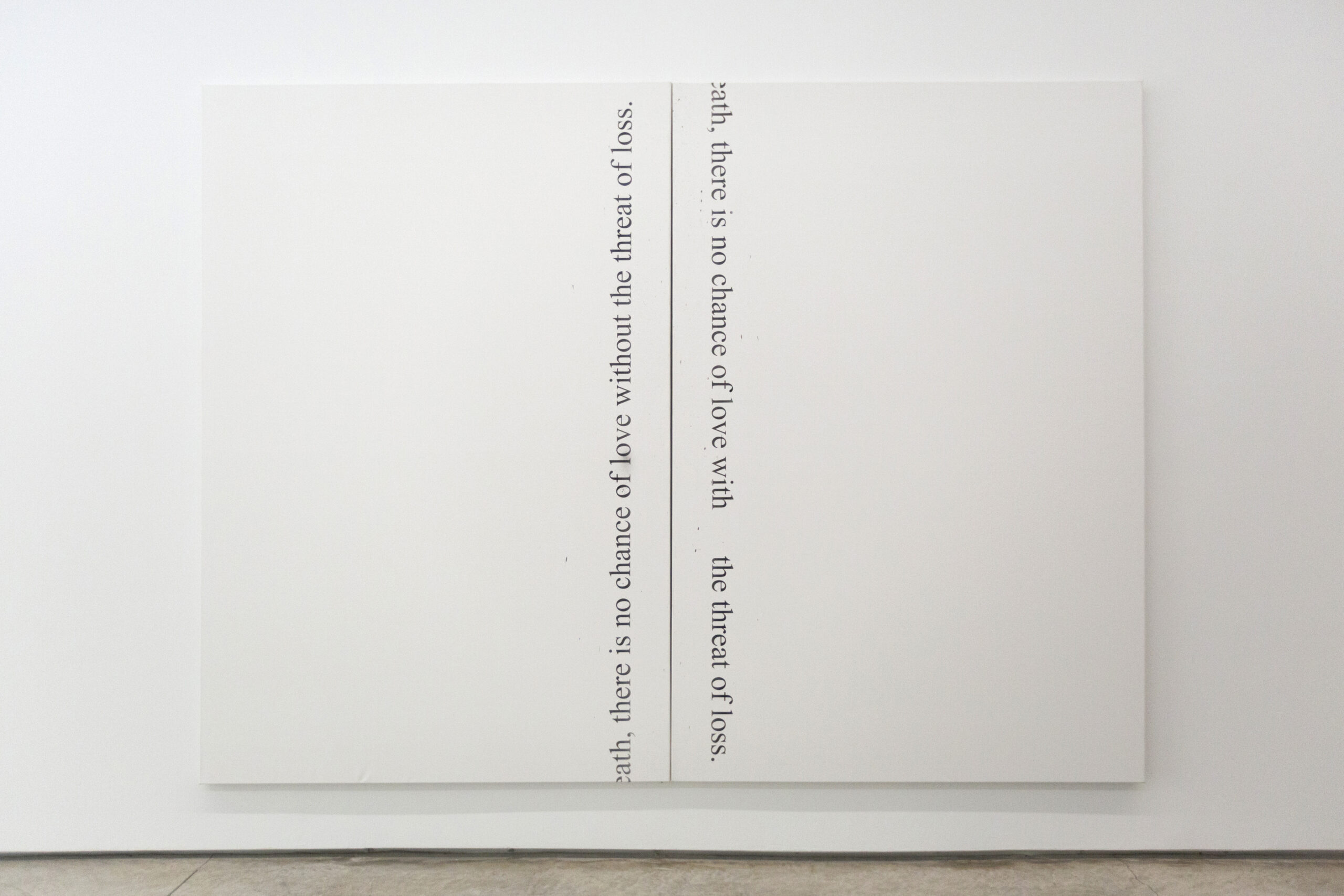

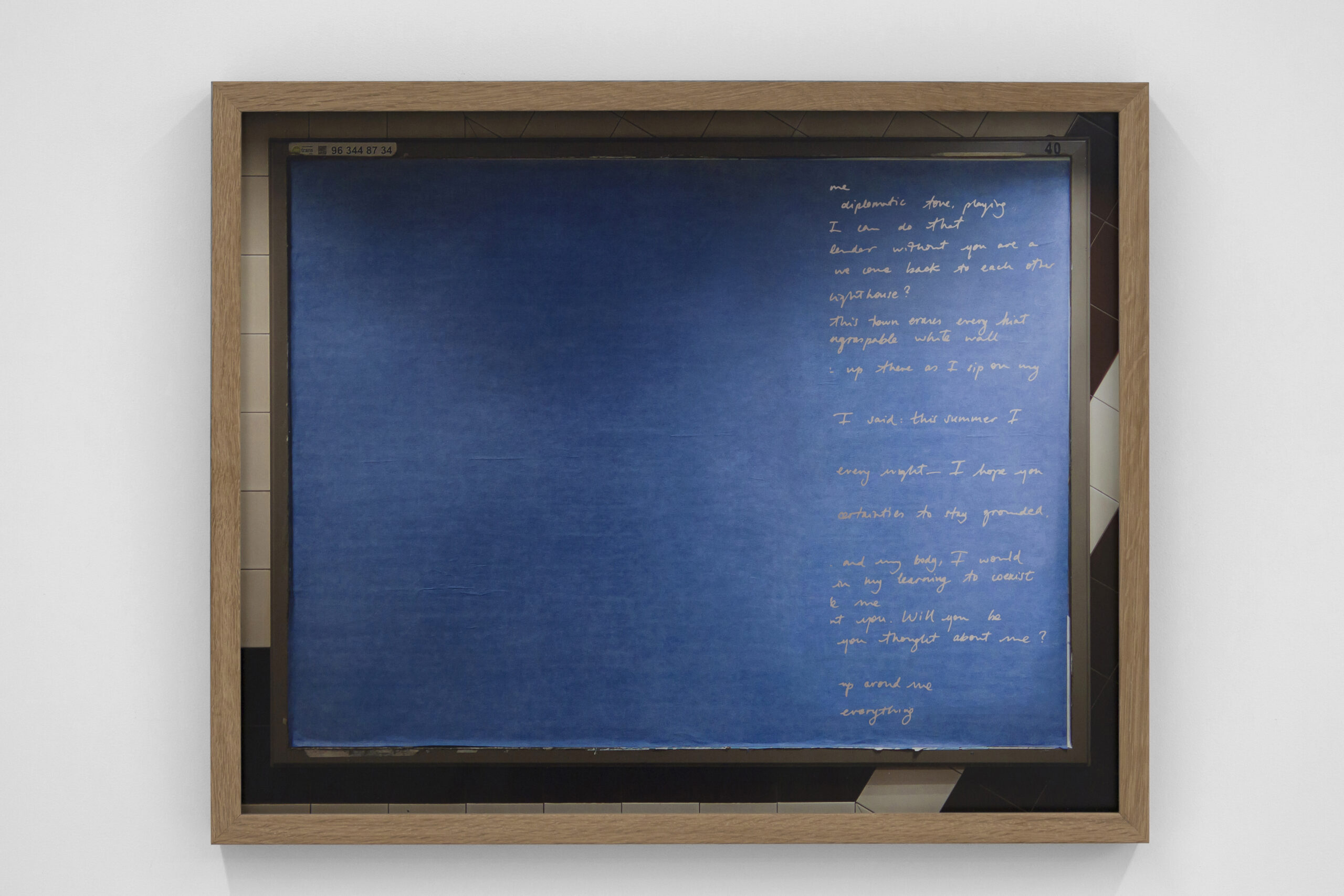

Felix Gonzalez-Torres took snapshots of the sky and sent them, like postcards, to friends. In the vastness portrayed in the images, the viewer finds themselves neither here nor there. On the back of one of these snapshots, he penned what would become the title of one of Tinaut’s recent works – Days of Clear Blue Skies. She told me that commercial billboards in Valencia’s subway are temporarily covered in blue (the backside of the paper used for advertisements) before the next poster is put up. After printing Gonzalez-Torres’ writing in vinyl, she installed the words in one of these blue expanses. In the following weeks, the image registered all kinds of human activities: spits, scuffs, tags, and paper tears. This intervention became a record of the physical movements of passers-by, almost like a palimpsest. This piece, like Gonzalez-Torres’ snapshots, lives in a state of in-betweenness as it wavers in the crosshairs of public and private, legible and illegible, near and far.

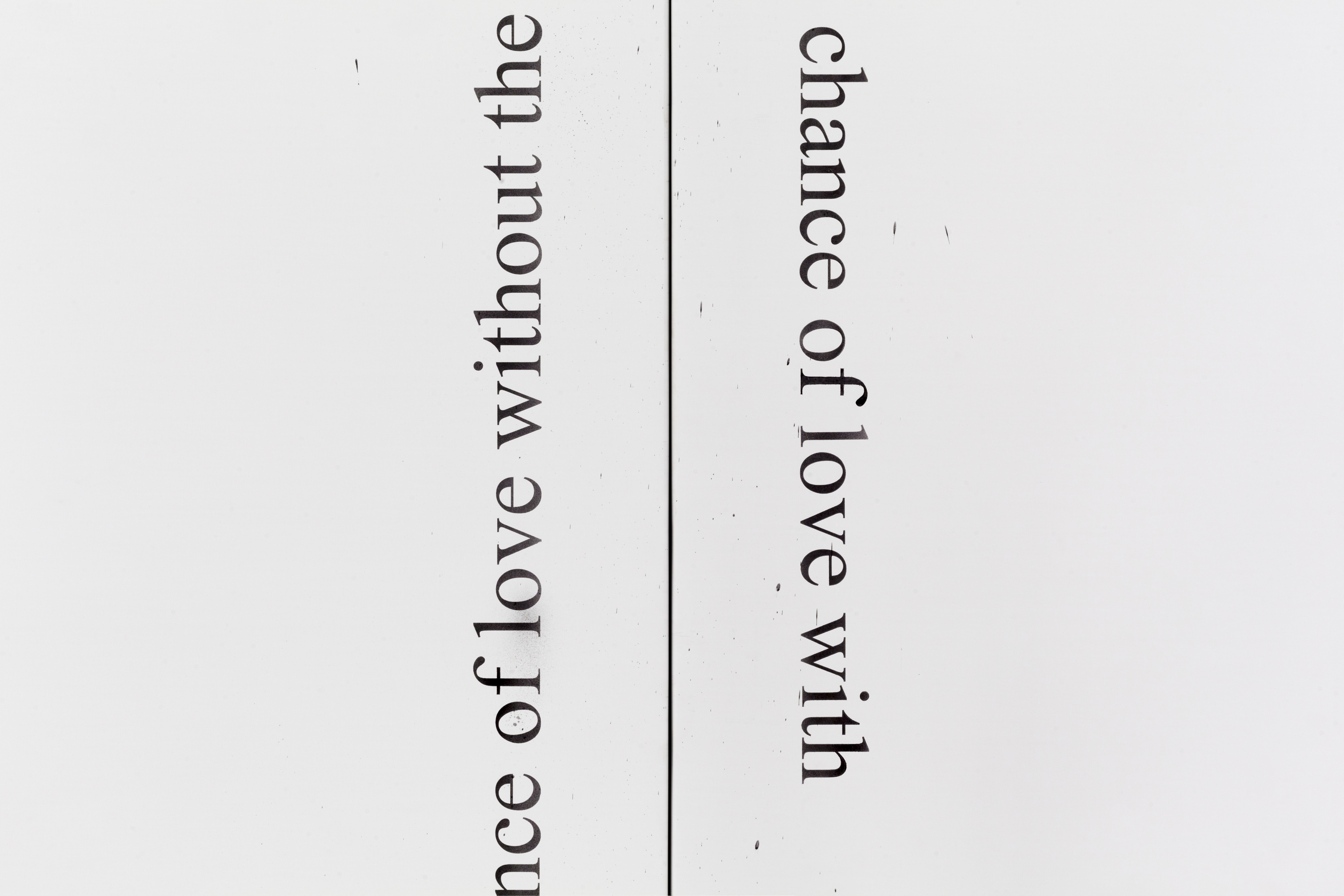

In 1797, Friedrich Schlegal wrote that “every sentence, every book that does not contradict itself is incomplete.” Untitled (The Chance) consists of two paintings, hung closely together on the wall. The text on one painting reads, “There is no chance of love without the threat of loss.” The other says, “There is no chance of love with the threat of loss.” In these two declarations, love and loss are inseparable, but the conditions under which the chance of love could exist are antithetical. Following Schlegal’s train of thought, this piece is complete because of its opposition and multiplicity. A desire and call for the more-than-one is present also in Cup (Two) two vessels joined by one handle. In this work, we can’t drink alone or the coffee from the second cup will end up in our laps (a scalding singularity?) and drinking it with another would require touch and negotiation. In both Untitled (The Chance) and Cup (Two), two are entangled and form something new.

Like the oceanographer gazing into the water over an unmapped section of the seafloor, we haven’t yet charted all the ways that our futures are wrapped up in each other. As I write this, the coronavirus pandemic continues to explode worldwide. Black Lives Matter protesters have continued to courageously fight for justice in enormous numbers for more than sixty days and counting. And the climate crisis is predicted to lead to a greater temperature increase in the next fifty years than it did in the last six thousand years combined. Our struggles rub against each other and shift like tectonic plates. Through these ever-shifting relations of touch, new bonds, new spaces, and a whole new spot of earth is created. James Baldwin interchangeably described the role of the artist and the lover: both bring new things to light and help us see things that had previously gone unnoticed. In the space of Tinaut’s exhibition, we are all artists and we are all lovers, splintering in a million directions and coming back together again.

Text written by Erin Johnson, translation by Laía Argüelles.