The Blood of the Earth

Wine is the birthplace of Western civilization. Ever since Prehistory, right up until the present day, wine has been a source of nourishment, of work, of inebriation and of life. Through the domestication of vines and the discovery of the process by which the juice of grapes is transformed into an ethylic elixir, wine is able to make us connect with the sacred in communion with nature, which is both ordinary and unpredictable. It has transmuted into a god and there have been gods who have been transformed into wine. It springs from the earth, but it requires effort. It gives life, but it also takes it away. During its making it gurgles and bubbles as if it emanating from open arteries. Wine is the blood of the earth and Greta Alfaro explores these relationships in an exhibition in which grapes are confused with the figure of Christ, winegrowers become the major artistic landmarks of our civilization, and Dionysius gets drunk on the body of the Saviour.

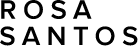

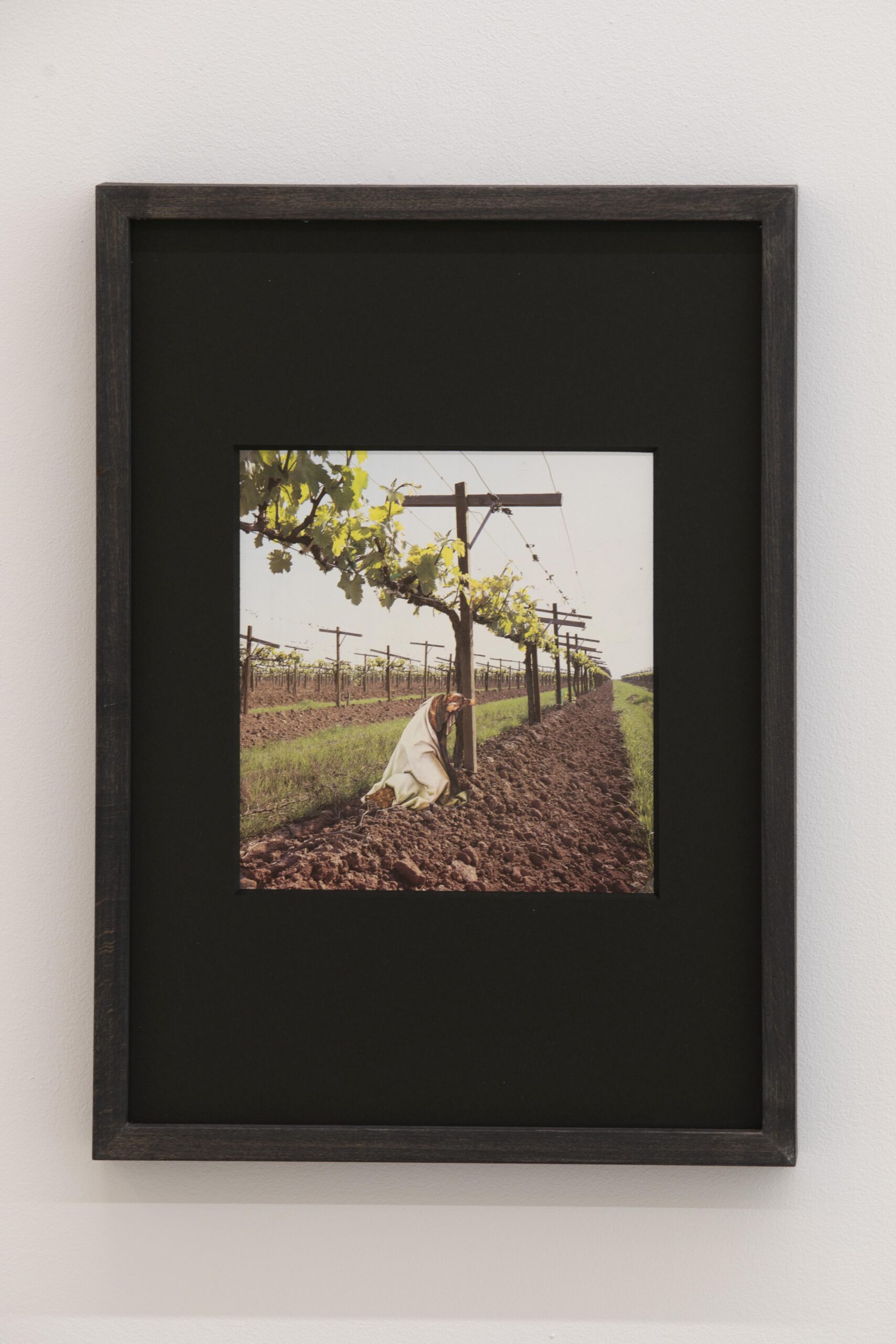

Wine is able to connect various worlds and to give coherence to human experience. The perfect metaphor of blood, it offers transcendence through a liquid that comes from grapes which is able to sublimate moods and to provide the body with nutrients. Considered one of the main foods throughout the majority of history, today it has lost this aspect of nutrition, yet it maintains the idea of sustenance through the work of field labourers who know the demands of the vineyard and what it means to spill your own blood on the land. Its subsistence depends on a fragile equilibrium, on a latent tension between human desires and the designs of nature, which can be equally generous and destructive. This idea, a constant in the work of Greta Alfaro, reminds us that our existence is precarious and is part of an environment that, at times, shows us a friendly face and other times a hostile one. The grapes mature under the golden sunlight, but when drought prevails these same rays of sun that caress the fruit can cause devastating fires that sow the death of the vine as they rage. And, in the midst of these forces of nature, subjugated to them, trying to appease them and to muster them in our favour, are the men and women who nurture the vines.

The processes of winemaking, which had varied very little over the thousands of years of the history of human civilization, have not stopped transforming over the last three or four generations. As we can see in the video “Los labradores” (Farm Labourers), winemaking is no longer a family-run business, associated with subsistence economy, but a paid employment subject to legislation, to the law of supply and demand, and to health and safety regulations. Although machinery and steel have replaced flesh and skin, behind the rhythmic movement of robotized mechanisms that process the juice of the grapes, the association with blood remains intact. Despite the break with the learning of the past, modernism has not been able to untie the bond between wine and life, through one of its most appreciated fluids.

This flow of blood, a symptom that the body still remains alive, is rendered in the video “Las labradoras” (Women Farm Labourers). Each blow of a boxer in the sack stuffed with pomace leaves an indelible wine stain that reflects the pain of the body of women farm labourers, subjected to the rigours of physical work in the fields and to the labour of giving birth at home. The traces left in the sack are the marks left on their skin. It is they who, with the blood of their uterus, perpetuate the painful miracle of life and who stain their hands harvesting the grapes from the vine and making wine. Since time immemorial they have been assimilated with the earth they work and, like the earth, it is expected that they bear fruit with their own blood.

The belief that menstrual blood served as nourishment for the foetus and, after birth, was transformed into mother’s milk, continued until not too many decades ago. Christian religion appropriated this common idea to turn the blood of Christ into wine, into milk, into nourishment for the children of God. The blood of Christ, “shed so that our sins may be forgiven”, was assimilated during the Middle Ages with menstrual blood, which was spilled every month to nurture the new creatures that were still to come. Wine drunk during the eucharist represents the blood of Christ turned into food for the soul, which will be born anew in the Great Beyond once our days on this earth are fulfilled. The body of Christ is feminized, it becomes earth, it becomes a bunch of grapes. His blood is transmuted into wine that flows from the wound opened in his side to be drunk.

Menstruation, transfusion, crop growing, industry and civilization are some of the subject matters addressed in “The Blood of the Earth”. This exhibition leads us from the roots of the vine to the sacred through wine and the many men and women who dedicate their lives to making this elixir that connects our bodies with the earth.

Isabel Mellén