Florencia Rojas

Fri May 19 - Fri June 28, 2024

LIKE A HOME

…a letter can always not arrive at its destination.[1] The point of departure for this exhibition is two first-hand accounts. Related anonymously, both accounts come from immigration detention centres or CIEs (for their acronym in Spanish, Centro de Internamiento de Extranjeros), one in Madrid and the other in Valencia. Ainara (pseudonym) was interned in the […]

…a letter can always not arrive at its destination.[1]

The point of departure for this exhibition is two first-hand accounts. Related anonymously, both accounts come from immigration detention centres or CIEs (for their acronym in Spanish, Centro de Internamiento de Extranjeros), one in Madrid and the other in Valencia. Ainara (pseudonym) was interned in the Aluche CIE in Madrid, while XXXX —whose real name we do not know—was interned in the Zapadores CIE in Valencia. Their experiences as migrants in Spain are different, but they share in common a period of forced detention in a CIE and the subsequent silencing they had to suffer, or put up with, given the vulnerability of their legal status and the violation of the rights included in current Immigration Law.

Despite the regime of hypervisuality in which we all live in the global north, we are surrounded by black holes, opaque places and buried stories. There are policies of visibilization and invisibilization of the past and the unpalatable present that call for work and reflection in order to be able to access narrations left outside the hegemonic system of representation.

My primary instrument for gaining access to these personal accounts is listening. And this listening generally goes hand in hand with personal relations that go beyond the actual project itself and come about organically through spending time together and creating a working context in which many decisions are debated and agreed. My intention is not only to relay these accounts but also to underscore the reasons why they cannot be conveyed first-hand by the people themselves.

Detention Centres

The name “Centro de Internamiento de Extranjeros”, literally Internment Centre for Foreigners, is a euphemism which endeavours to disguise the fact that CIEs are prisons for migrants. These centres are not acknowledged as penitentiary institutions, thus favouring invisibility and impunity for what goes on inside them.

CIEs are racist prisons where the rights of the people detained are constantly violated. These centres are part of the machinery of migratory necropolitics and are interstices in which people are deprived of their dignity and their skills, and turned into victims of the perversity with which the system produces non-citizen persons, administratively speaking. (Paramés & Peñalosa, 2021)

Over the last century and a half, immigration has served to generate not just sufficient labour force but the excess which the capitalist market requires. Spain urgently needs a browbeaten and vulnerable workforce. That’s why borders are not just shared with neighbouring territories; Spanish immigration laws turn the whole of the territory into a frontier border territory with the CIE being a prime example of an internal border. The mission of these institutions is not to “redirect” the vital trajectories of detainees but to convey a differential disciplinary message to the whole of the immigrant population that coerces them into accepting whatever working conditions they are offered. (Simón, 2022)

Given the systematic violation of rights in CIEs, the threat of deportation often means that complaints or cases of abuse are not reported. This is because the result of filing a complaint is generally deportation: a one-way flight back to where you came from and another case closed.[2] And so there is nothing to stop these violations of right in CIEs from being perpetuated. The machinery is so well-oiled and designed that anyone who speaks out is sure to get a seat on the next available flight. And once deported, these people disappear from the system, they no longer exist inside our borders and we usually hear no more from them. A quick end is put to life projects in the countries to which they emigrated, and they are abandoned to fate in their home countries (or third countries), the very places they left in many cases because of war, persecution or extreme poverty. This is the case of XXXX, a young man who, after an attempted escape from the Zapadores CIE, was put through hell in solitary confinement—more or less a prison within a prison. There he suffered multiple forms of violence to which he responded with active resistance, which I would like to focus on. In acts of disobedience like setting a mattress on fire or his repeated attempts to escape, we can catch a glimpse of the fissures opened up by showing spirit and the capacity for critical response that arise in limit situations like this.

I, XXXX

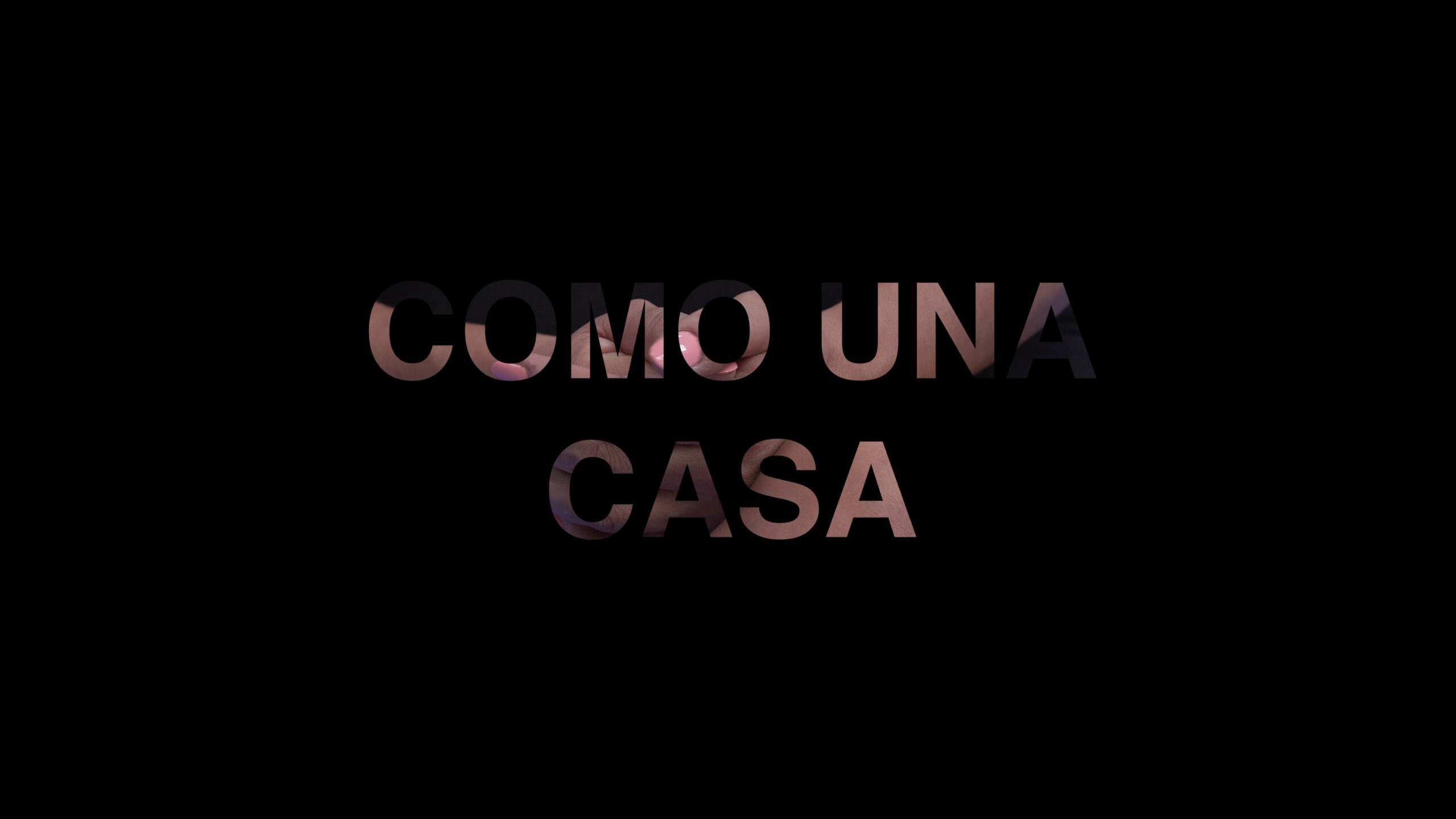

XXXX denounced the abuse suffered and, once again, the story ended up with deportation and another file closed. Before leaving, XXXX wrote a letter by hand in which he detailed his experiences in Zapadores CIE, an artefact which is a cornerstone for this part of the exhibition.

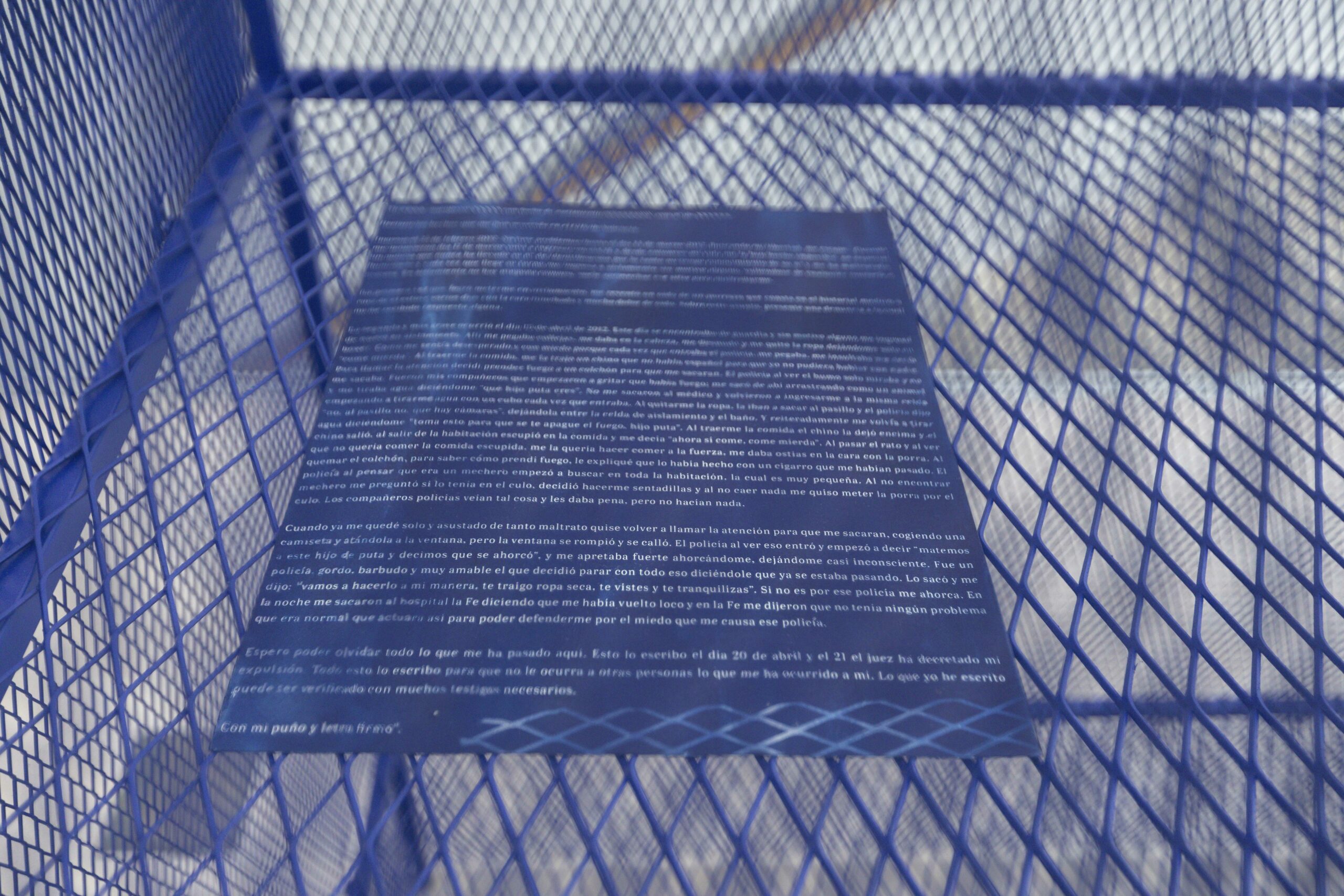

The spaces configured by institutions of detention and repression articulate the lives of what happens inside. The CIEs contain overcrowded cells with blue iron bunkbeds, the same furniture also to be found in the tiny solitary confinement cell in which XXXX was locked up. The interpretation of this meta-detention is formalized in a sculptural proposal called Yo, XXXX (I, XXXX) which replicates one of the bunkbeds from the CIE and adds other elements of confinement to give shape to a bed-cell of sorts. If we peek through the grating, we will see a cyanotype with the transcription of the letter XXXX wrote before being deported.

The letter tells a story that is not depicted because it contains a number of events that Power always manages to keep outside the picture. I believe it was necessary to somehow stage—in this case through the format of a storyboard and script—an overwhelming and turbulent sequence ripe to be turned into a movie.

The prison turned into another prison

In the case of the CIE in Madrid, there is a specific strategy to go undetected which is involved in the very name of the centre: Aluche CIE. The name conceals the fact that the Aluche CIE is really in Carabanchel, in the grounds of a former prison. This responds to a deliberate strategy of erasing any possible connection between one place and the other. The demolition of the panopticon of the Carabanchel prison in 2008 was an operation to wipe the slate clean on the shameful and repressive past of the most infamous prison during Franco’s regime. At the same time, this attempt to erase the memory was also an attempt to free the neighbourhood of Carabanchel of the stigma related with the prison and with delinquency, a stigma now cast on the figure of the precarious immigrant and relocated to the adjacent neighbourhood of Aluche. (García García, 2012)

In addition, there is another element that favours the invisibilization or camouflage of the CIE in the neighbourhood: the architecture of the building in no way corresponds to the usual design of spaces of repression. In fact, it has a colourful, playful appearance reminiscent of other types of places, and some people say it even looks like an Ikea. When the building was refurbished to turn it into a CIE, it was aestheticized to make what goes on inside it invisible. The walls were painted yellow and the windows were covered with blue screens to hide the bars behind them. Furthermore, the courtyard was covered over with a roof. These architectural elements prevented detainees from seeing the outside world and, vice versa, from the outside you could not see what was happening inside. This, combined with the colourful domes added on, means that many local people in Carabanchel have no idea that inside this singular building, directed by the National Police, immigrants are deprived of their freedom.

The Aluche CIE was opened in 2005 following the refurbishment of the former hospital of the Carabanchel prison undertaken by the architect Adolfo Morán who deployed a whole rhetoric of transparency, claiming that it is “an environmental building, with a roof that can be raised and lowered, which reminds us that the word ‘police’ stands for transparency.”[3]

One of the most perverse elements the architect included in the refurbishment of the building were the aforementioned blue screens. These metallic coverings perforated with small holes allow a certain amount of light to enter but prevent visibility from inside out and from outside in. However, the bars on the windows of the CIE can be readily seen at night-time when the lights inside the cells are switched on.

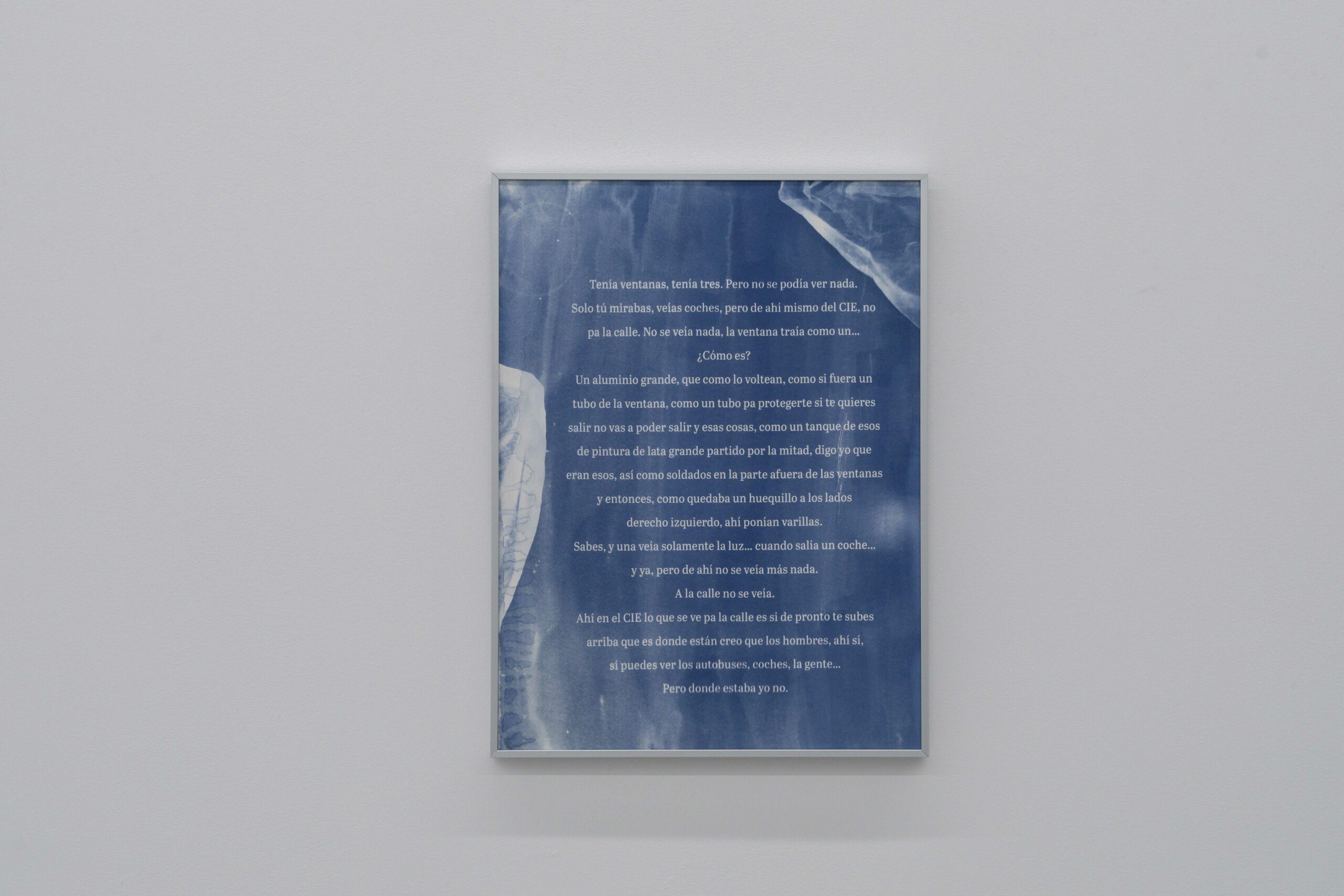

Sunshade

The first part of this project consisted in replicating one of the screens from the CIE to signal the opaque regime of the whole deportation device through a specific architectural element that, to my way of thinking, synthetizes the research in a visual arts project that operates as a trace of the process. The work Quitasol (Sunshade) consists in this element taken out of context and accompanied by an image in which one can read the description Ainara makes of the windows. The sculpture, which filters the light entering the cells, also includes the detainee’s words are revealed by sunlight, using the nineteenth-century cyanotype technique in which images are produced by exposure to sunlight. There is an allegorical intention to remove this opaque screen in order to listen to what is being said inside.

Ainara was arrested by the police and interned in the CIE for a month because of her irregular undocumented situation. Migrants interned in a CIE almost never speak about or share their experiences. This is because, after the period of detention, they are either deported or allowed to stay in Spain but in the same irregular situation without documents. This condition is hard to resolve and means that these people are unable to identify themselves, file complaints, nor tell their story for fear of being detained again and/or deported.

Like a Home

At this juncture in the process I decided to make an audiovisual piece in which another person would embody Ainara’s story. This person, whose legal situation is in order, operates like an intermediary body, a loudspeaker, a medium, a channel for knowing Ainara’s experience first-hand. To undertake the piece Como una casa (Like a Home), I borrowed inspiration from the Verbatim Theatre technique, which gives rise to dramatized performances that reproduce transcriptions of real testimonies. My point of departure for the script was the recording of a long phone conversation I had with Ainara in which she told me about her experience as a migrant in Spain and all the institutional violence to which she was subjected.

Ainara’s story touches on several concerns illustrative of certain current problems which need to be addressed. Her story brings into question and forces us to think about issues like sex work, immigration law, the penitentiary system or structural racism and sexism. It is impossible to speak about sex work without speaking about migration. The arguments for abolitionist positions on prostitution ignore immigration law, which is the reason why so many women choose sex work over the precarious and enslaving jobs that Spain and its laws imposes on migrants. Nor is it possible to speak about migration without speaking about coloniality. As argued by Françoise Vergès (2022), among many other authors, colonial slavery plays a foundational role whose consequence is that racism continues to undergird institutions of power and to drive policies of expendable lives.

It was important that the person embodying Ainara’s story would be someone whose place of enunciation brings into question the issues cutting across the story. After agreeing with Ainara, I contacted the Mexican artist and actress Linda Porn, who is also a sex worker, an activist for the rights of sex workers and antiracist activist. Linda agreed to play the character and, from that moment onwards, we worked as a three-person team to produce the piece. Como una casa combines Linda Porn’s performance with real extracts from the phone conversation I had with Ainara. One can sense that there are two voices telling the same story, one voice which is given a body and the other a distant voice we are unable to identify.

Ainara and XXXX are our neighbours, the Valencia CIE is located in the Les Corts neighbourhood, the Madrid CIE is in Carabanchel. Our cities have an underbelly we do not want to see, places where, as Butler explains (2010), “some ‘subjects’ are not quite recognizable as subjects, and there are ‘lives’ that are not quite—or, indeed, are never—recognized as lives” and so, therefore, they don’t deserve to be grieved.

Florencia Rojas, 2024

Acknowledgements:

Ainara, XXXX, Linda Porn, Julia del Portillo, Asociación Mundo en Movimiento, CIEs NO Valencia, Asociación Aprosex

References:

BUTLER, J. Frames of War. When is Life Grievable?, London: Verso Books, 2010

GARCÍA GARCÍA, Sergio: Co-producción (y cuestionamientos) del dispositivo securitario en Carabanchel. Doctoral dissertation directed by Ana María Rivas Rivas and Mariantonia Rossana Cassigoli Salamon. Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Department of Social Anthropology, 2012

PARAMÉS, M. & PEÑALOSA, M.: Regularizar lo inhumano, una aproximación crítica al Centro de Internamiento de Extranjeros de Madrid desde el género y la salud. Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung, 2021

SIMÓN, P. Miedo, viaje por un mundo que se resiste a ser gobernado por el odio, Barcelona: Penguin Random House Grupo Editorial, 2022

Various (CIEs No Valencia): ¿Cuál es el delito? Informe de la Campaña por el cierre de los centros de internamiento: el caso de Zapadores. 2012

VERGÈS, F. A Decolonial Feminism, London: Pluto Press, 2021

[1] DERRIDA, Jacques: The Postcard. From Socrates to Freud and Beyond, trans. Alan Bass. Chicago & London: The University of Chicago Press, 1987, p. 123.

[2] As borne out by the reports published by CIEs NO Valencia where we can a large number of cases in which the story of complaint-followed-by-deportation is repeated.

[3] GARCÍA GARCÍA, Sergio: Co-producción (y cuestionamientos) del dispositivo securitario en Carabanchel. Doctoral dissertation directed by Ana María Rivas Rivas and Mariantonia Rossana Cassigoli Salamon. Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Department of Social Anthropology, 2012.