Joan Sebastián

March 27 - May 23, 2025

After Opalka

Time as Space as Drawing. Deciding how to approach an artistic project, particularly at the very outset, is not far removed from choosing the tone when writing a text. Any given decision must weigh up possible options, but there is one in which you have to decide what to say and how to say it. […]

Time as Space as Drawing.

Deciding how to approach an artistic project, particularly at the very outset, is not far removed from choosing the tone when writing a text. Any given decision must weigh up possible options, but there is one in which you have to decide what to say and how to say it. A pensive frown, staring vacantly into space, a shrug of the shoulders, cracking a wry smile… the gestures that speak of the complexity of a simple action are parts of a non-verbal language rife with meaning. Sometimes, however, it turns out that choosing a theme can be an action resolved the other way around: it’s the theme that actually chooses the chooser. Like a character in search of an author willing to be chosen. And while this project is artistic and not directly related with literary concerns, it does involve a narrative, since its purpose is to convey something it has decided to say.

Throughout his extremely coherent career, Joan Sebastián has accrued a wide-ranging, profound body of work that has circulated more slowly (and covered less ground) than one might have expected; however much that could sound, here and now, like simply paying lip service. Around twenty years ago, his work took an internal shift from painting to drawing and became more structural, sober and elementary, less diverse. The techniques he employs were confined to a narrow scope, almost a closed circuit of graphite, colour pencil and pastel, and always with paper as his go-to support; a universe that operates like a network of apparently flat constellations, at times perhaps even boring when viewed from the optic of the current logic of immediacy and overproduction. That said, and therein lies the quiet revolution of his work, the apparent tedium is the adventure of time, of its rapids and its plains, its deserts and its storms; of the abundant downtimes that fill the space between the more or less memorable events of our lives. Because, here, time is a space that has been conquered, treated as an equal, vanquished by the unwavering action of an ordinary mark on paper.

After Opalka brings together, firstly as a series, all the key features of J. Sebastián’s practice, which include the unhurried pace for thinking about and producing his works; a reflection on time understood as a two-faced Janus, each one represented by Chronos and Kairos; references to drawing as writing and, vice versa, writing as artistic marks; the self-referentiality of the art world, explored incidentally in various series and foregrounded in Capturas (2018-2020), and now consciously embracing the idea of continuing a task cut short by the death of Roman Opalka which J. Sebastián takes on as his own.

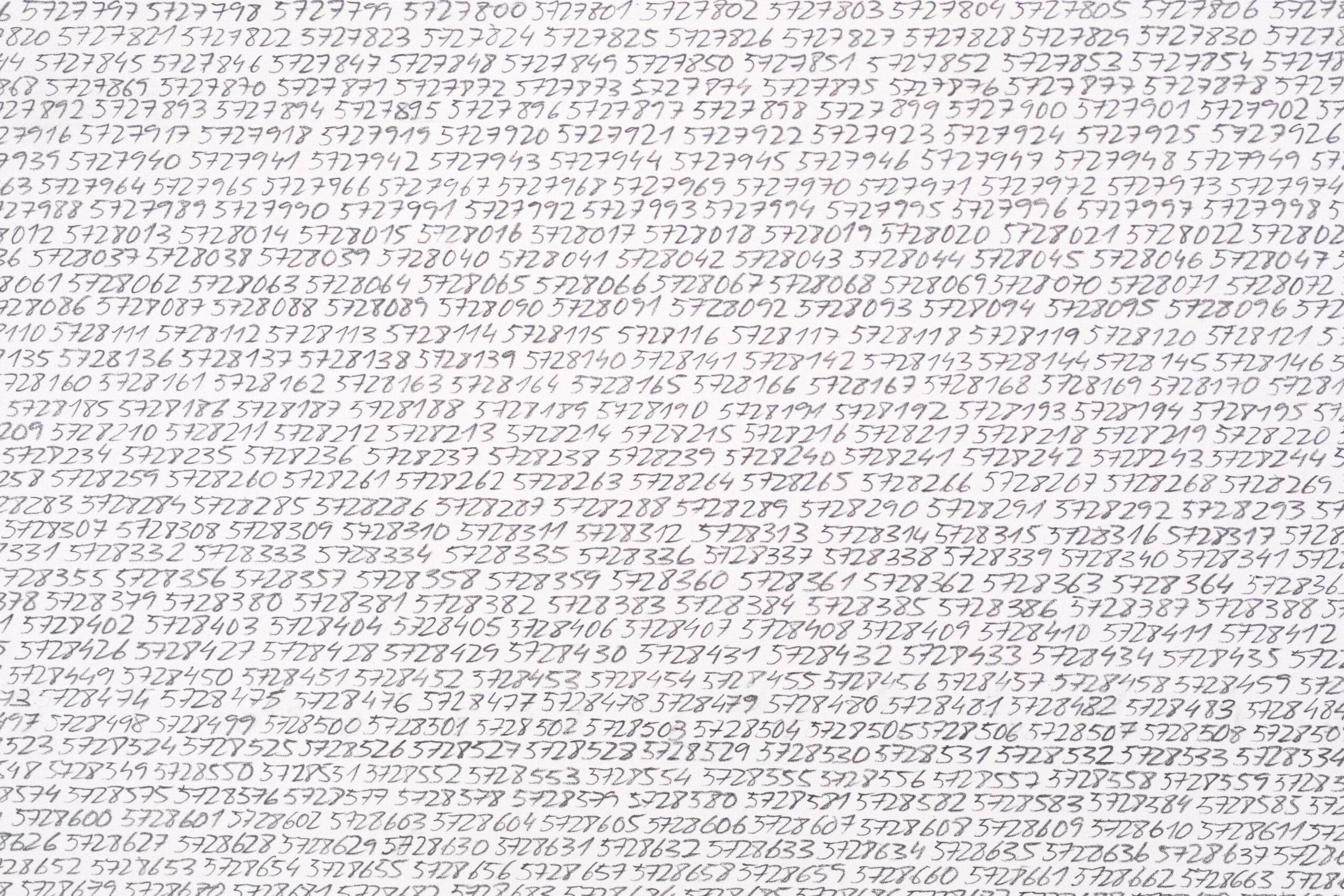

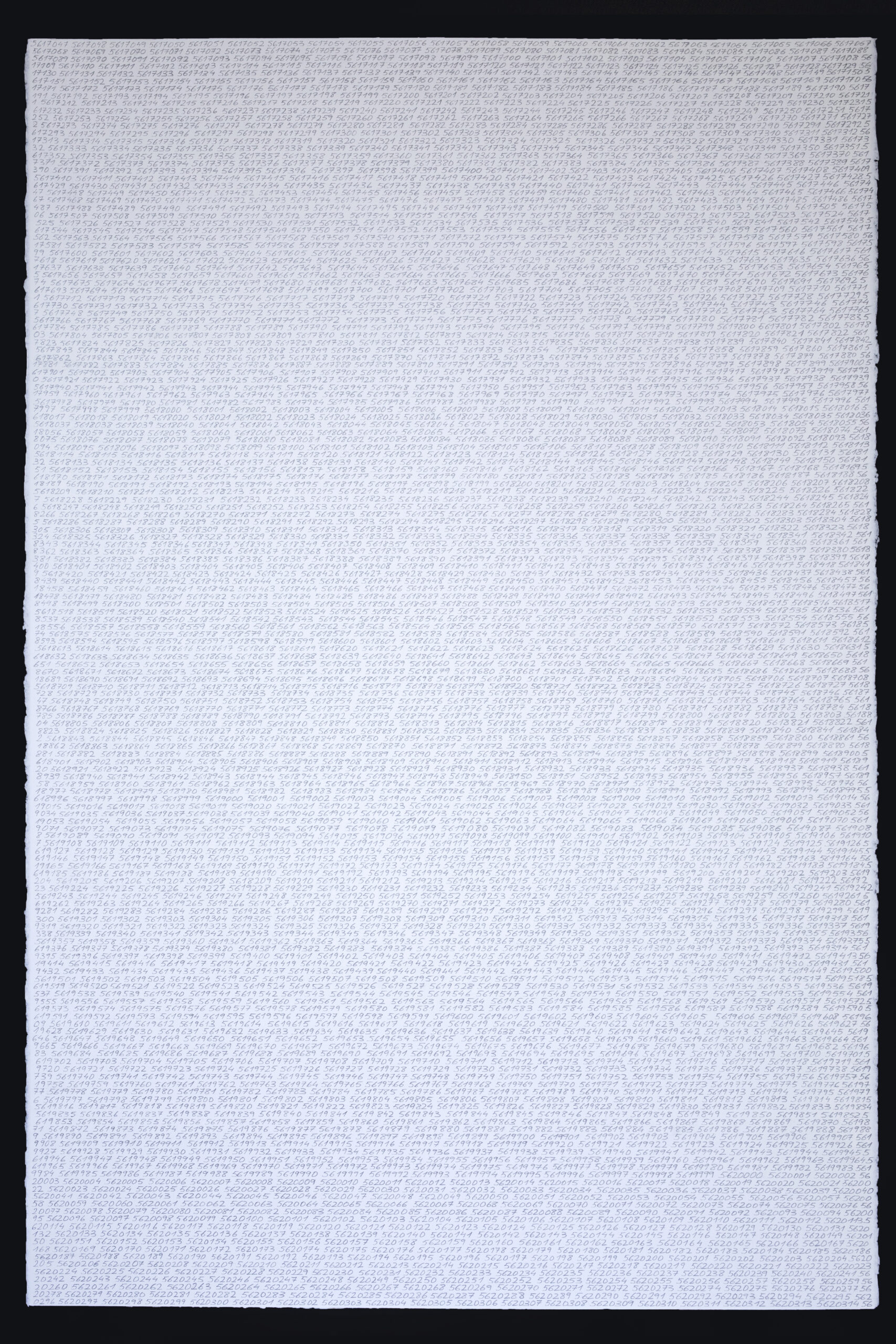

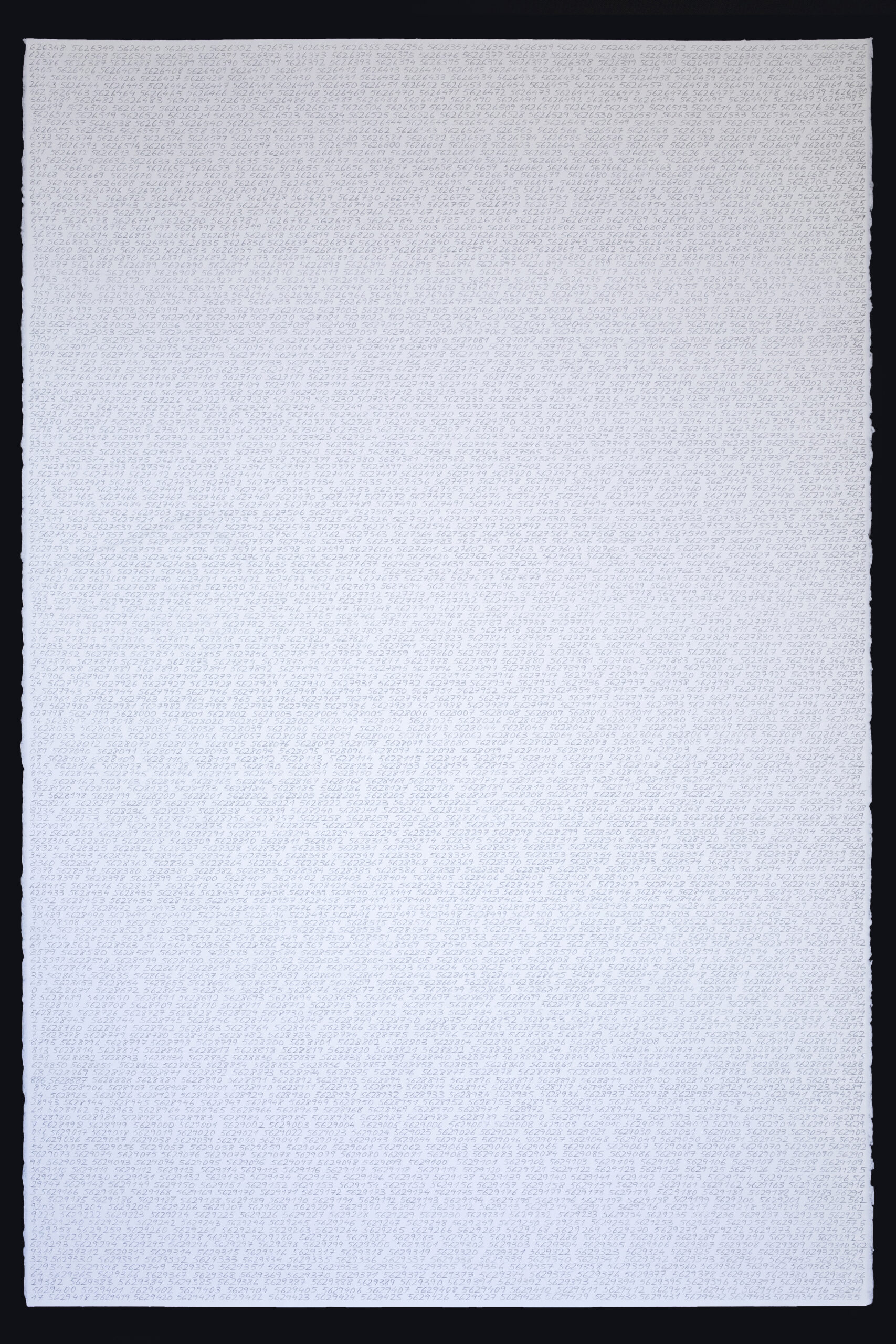

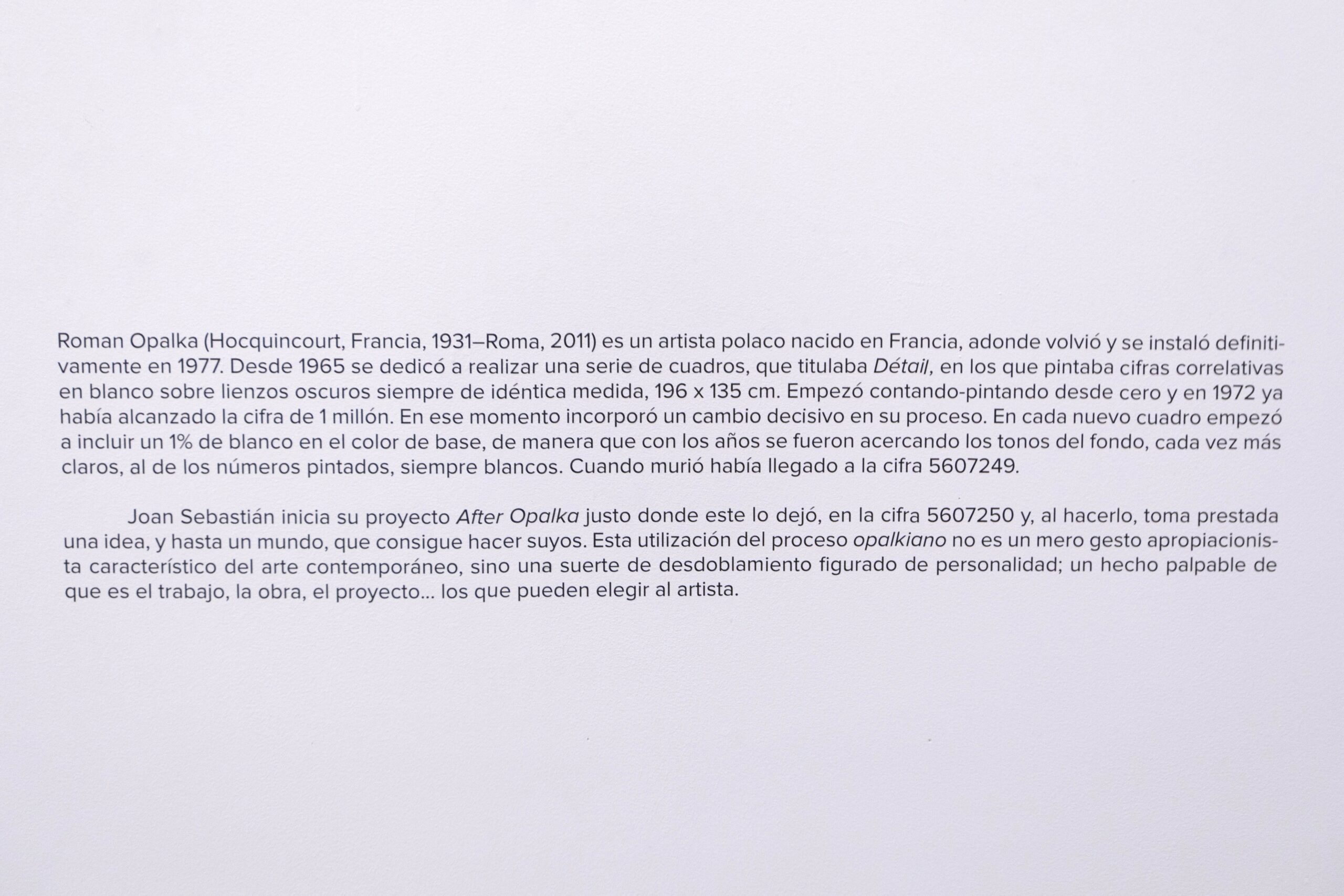

Roman Opalka (Hocquincourt, France, 1931–Rome, 2011) is a Polish artist who returned to and settled in France, the country where he was born, in 1977. Earlier, in 1965, he had started work on a series of paintings, which he called ‘Détails’, in which he painted correlative numbers in white on dark canvases always measuring the same size, 196 x 135 cm. He started counting-painting from one and by 1972 he had already reached 1 million. At this juncture he decided to add a change to the process. From now on in each new ‘Détail’ he would add 1% more white to the colour of the ground, in such a way that with the passing of the years the tone of the ground became increasingly closer to that of the painted numbers, which were always white. By the time he died he had reached the number 5607249.

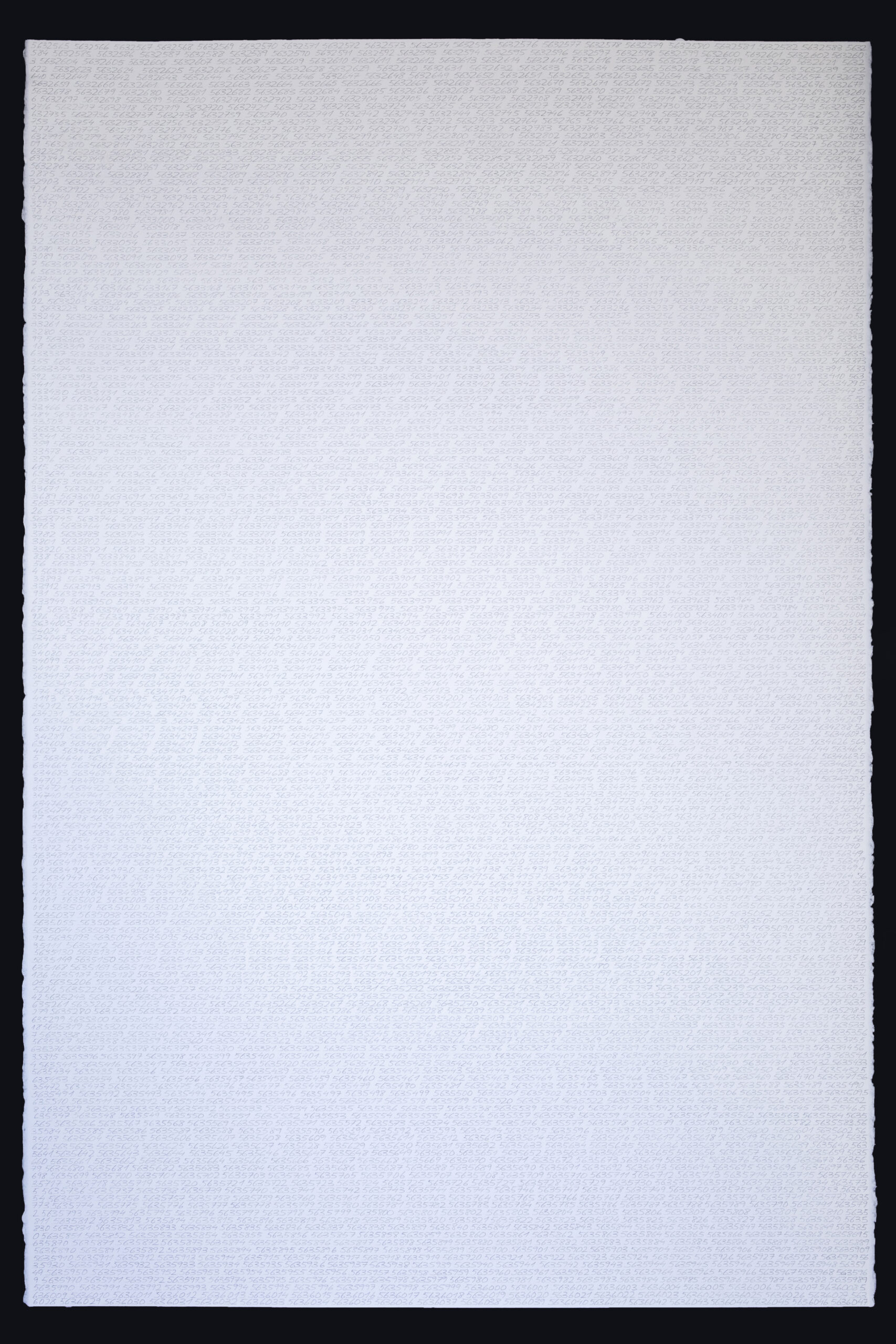

Joan Sebastián started his project After Opalka precisely where Opalka left off, at the number 5607250 and, in doing so, he borrows an idea, and even a world, which he manages to make his own. This use of Opalka’s process is not the simple appropriationist gesture proper to postmodernism, but rather a kind of figurative split personality; tangible proof that it is the work, the practice or the project that can choose the artist. Of course, the difference between their respective worlds and processes is patent. Where Opalka painted, Sebastián writes, and does not even draw: it is the drawing that takes shape with the written set of numbers; as opposed to the French-Polish artist’s always lighter figures against darker grounds, the Valencian artist evolves progressively modifying the resistance of the graphite: ranging from the lower numbers which are the hardest, to the softest and most intense and, then, back again, creating a kind of wave of intensity. Where Opalka turned his process into a polyphony of mediums, as he began to add recordings of his voice counting the numbers on the canvas and to take a photo of himself in front of each one, Sebastián only writes numbers with pencil that, when taken together, form a drawing; once again, and it is important to underscore this, there is a dogged return to basics, to the most elementary level of expression, to the structural and apparently most straightforward.

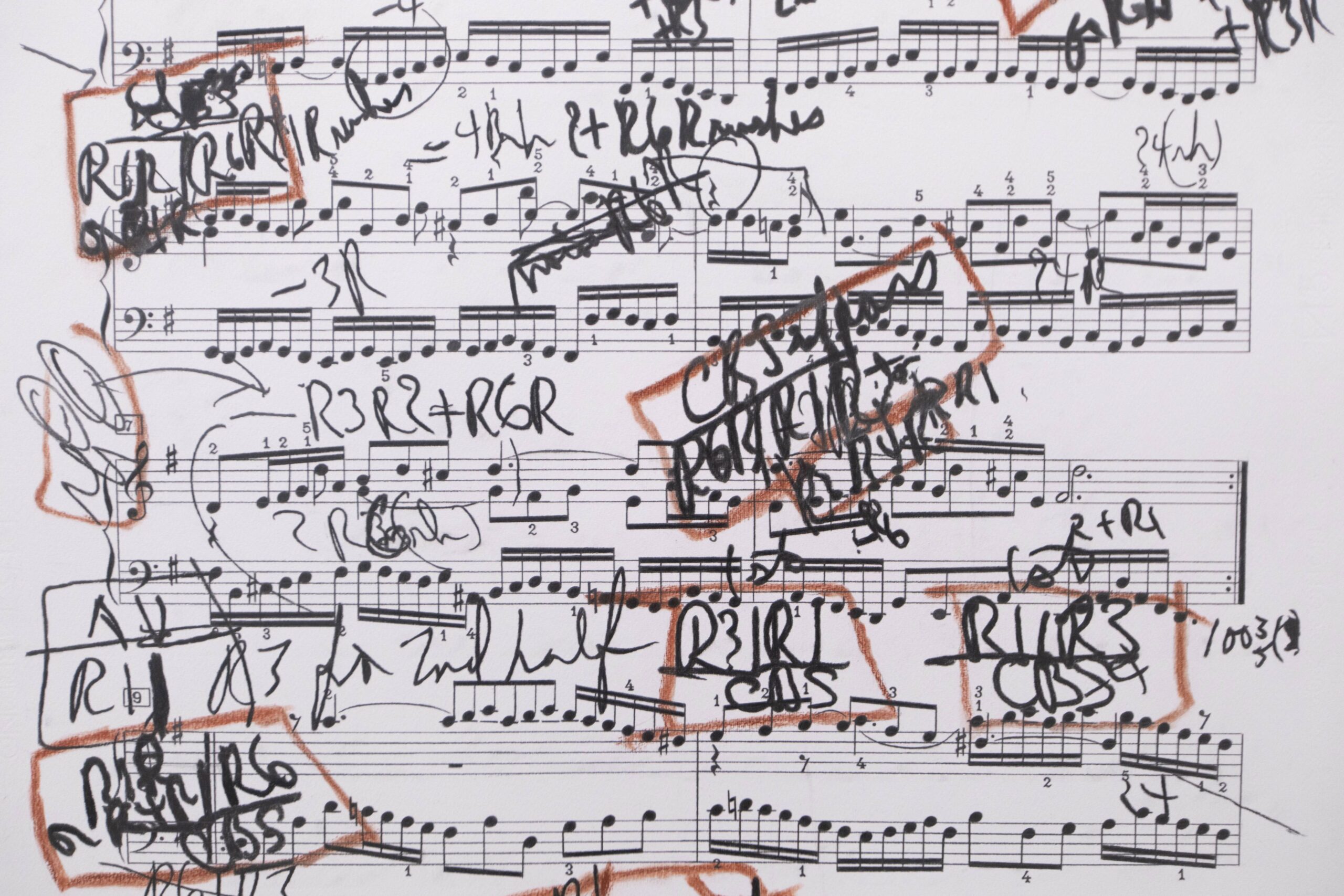

After Opalka also brings together, secondly as an exhibition, all the key features of J. Sebastián’s practice. The exhibition is conceived as the interconnection of two parts that coincide with the two floors of the Rosa Santos gallery. While the time (and number) line composed of 31 drawings in the series After Opalka is presented in the basement, six drawings of six music scores are shown on the ground floor. Four of the latter are empty, the drawing consisting of the lines of the staves and keys ready to be filled in. The other two are manuscript scores by J. S. Bach and by Glenn Gould and highlight the difference of style between the strokes. On one hand, the drawing shows the staves and keys, similarly to the four empty ones; on the other, in the drawing of Bach’s score, for instance, one can observe his signature in the handwritten music notes. Meanwhile, in Gould’s score we can see his hurried, impassioned notes written in black and red on Bach’s score for “Variatio 3 a 1 Clav.” from the Goldberg Variations. Sebastián invites us to play a game of mirrors between originals and copies, between first version and their countless variations. Aren’t Gould’s annotations an interpretative obsession of Bach’s variations? Aren’t all interpretations a sort of obsession to try to grasp what the author wanted to say when he conceived and created it? If J. Sebastián takes Opalka’s Détails as a continuation of his own work and makes them his own, is it not a similar approach to what Glenn Gould took with J. S. Bach’s Goldberg Variations? And, finally, would it even be possible for the research, processes and results of culture to continue existing if they were not conceived from what has already been said and done?

Any artwork that starts out from an after or an après demarcates a playing field that necessarily includes everything that came after the suffixed concept, after the introduction that immediately signals its intentions. After Opalka also brings together all the Ulysses in the series Jueves y sábado, and the sudokus that are gradually solved in each successive piece of the polyptych. In other words, all intentions begin and end in each work, as if every attempt to be a “part” implicitly contained the “whole” it aspires to complete. The idea of time J. Sebastián uses and reproduces fills a space that can only be occupied by drawing; like a shudder that runs through a body which, once gone, can only be recorded with a routine, repetitive and yet irreplaceable gesture.

Álvaro de los Ángeles